"Begin Again, Let Go": Fallout New Vegas, the Decline of the West, and the Birth of a New High Culture

An Analysis of the Spiritual Paralysis of Historical Nostalgia and the Lonesome Road Back to Organic Tradition From Old World Blues

Section 1: Old World Blues in Fallout: New Vegas

Fallout: New Vegas, released in 2010 by Obsidian Entertainment, is widely regarded not only as a hallmark of role-playing design but, in an esoteric sense, the game also acts as a profound meditation on civilization, memory, and the perils of nostalgia. Among its most enduring thematic contributions to the Fallout series is the concept of "Old World Blues", a multifaceted term that threads its way through the main game and its downloadable content (DLC), serving as a metonym for civilizational decadence and the dangerous allure of the past, a metaphysical haunting. While the phrase first appears explicitly in the DLC of the same name, it encapsulates a larger theme that spans the entirety of New Vegas’s narrative and its setting: a post-apocalyptic Mojave Wasteland haunted by the ghosts of a world that destroyed itself.

Old World Blues is not merely about longing for a lost era. It is about the psychological and ideological paralysis that results from refusing to let go of what once was. In the game, nearly every major faction is a reflection or more fitting a distortion of a pre-war ideal. Mr. House, the reclusive and godlike CEO of RobCo and ruler of New Vegas, is a technological immortal being who has literally preserved himself from the pre-war era in cryogenic stasis. His vision for the future is one where the pre-war technocratic capitalistic world is restored under his singular direction. The New California Republic or NCR, with its bureaucracy, elections, and patriotic iconography, tries to resurrect the liberal democratic order of the United States or the ideal of the American democratic mythology, complete with corruption, expansionism, and inefficiency. Caesar’s Legion, the most overt pastiche of historical resurrection, reimagines ancient Rome through the lens of brutality, discipline, and slavery—an attempt to escape the decadence of the old world by reverting to an even older, supposedly purer form. Even the Brotherhood of Steel is a kind of religious order preserving the relics of technology, much like medieval monks who preserved knowledge through the Dark Ages and the Catholic Knightly orders of the Crusades. In this thematic landscape, the Mojave Desert becomes more than just a war-torn frontier; it becomes a liminal space where ideological ghosts fight over the corpse of America. Fallout: New Vegas forces the player to engage with these remnants not just as narrative flavor, but as pivotal choices. The game’s brilliance lies in how it compels the player to reckon with each faction’s interpretation of what must be salvaged, what must be discarded, and what future should be built. Mr. House believes in a meritocratic technocracy, ruled by the enlightened few. The NCR represents democratic imperialism, spreading its values regardless of whether they are appropriate to the land it seeks to control. Caesar’s Legion claims to offer unity and order at the cost of freedom and humanity.

Yet all these factions suffer from the same fundamental flaw: they are attempts to recreate or reassert the old world, not forge something truly new. Mr. House’s vision is sterile and autocratic, devoid of real human flourishing. The NCR, for all its pretensions of justice and progress, is crumbling under its own weight of ideology and ambition. Caesar’s Legion, built on conquest and terror, is as unsustainable as it is barbaric. These entities, like the casino ruins of the Las Vegas Strip, mocked up to look their former forms before the war, are facades—preserved monuments to a dead world. The people of the Wasteland are paralyzed by Old World Blues.

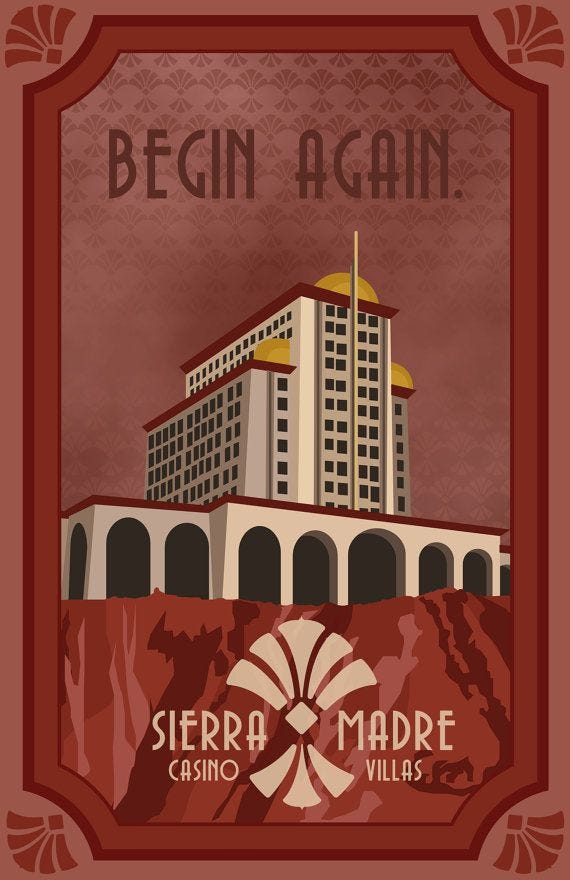

The DLC content further deepens this metaphor. In "Dead Money," the player is drawn into the Sierra Madre, a luxurious casino locked in a time capsule just before the bombs fell. The story centers on Father Elijah, a former Brotherhood of Steel Elder obsessed with harnessing the casino’s mythical technology to impose a new world order. His madness is a direct result of his inability to move past the old world’s promise of salvation through technological progress or Techne. The characters the player meets—Dean Domino, Christine Royce, and Dog/God—are themselves haunted by traumas and past obsessions. Sinclair, the casino’s creator, who lived before the war and built the Sierra Madre as a shrine to a woman who betrayed him, turning his monument to love into a mausoleum of obsession. The DLC’s tagline— sung by Vera Keyes "Begin again, Let go"—echoes throughout the player’s journey, culminating in the realization that salvation and freedom come only through release, not control.

"Honest Hearts," the next DLC, explores another side of this theme. Set in Zion National Park, it reveals the devastation wrought by Caesar’s Legion and the complex interplay between tribal cultures and the remnants of organized religion. The New Canaanites, a Mormon offshoot trying to spread civilization through peaceful means, are almost annihilated by the White Legs. Joshua Graham, the Burned Man and former Malpas Legate of the Legion, embodies the tragic irony of the old world’s brutality. Once a figure of terror, now penitent and broken, he is still caught between vengeance and redemption. The tribes in Zion, led by Joshua, must choose between becoming tools of vengeance or seeds of renewal and moving on from revenge. Even here, the temptation to cling to old forms of justice and power threatens the fragile emergence of something new.

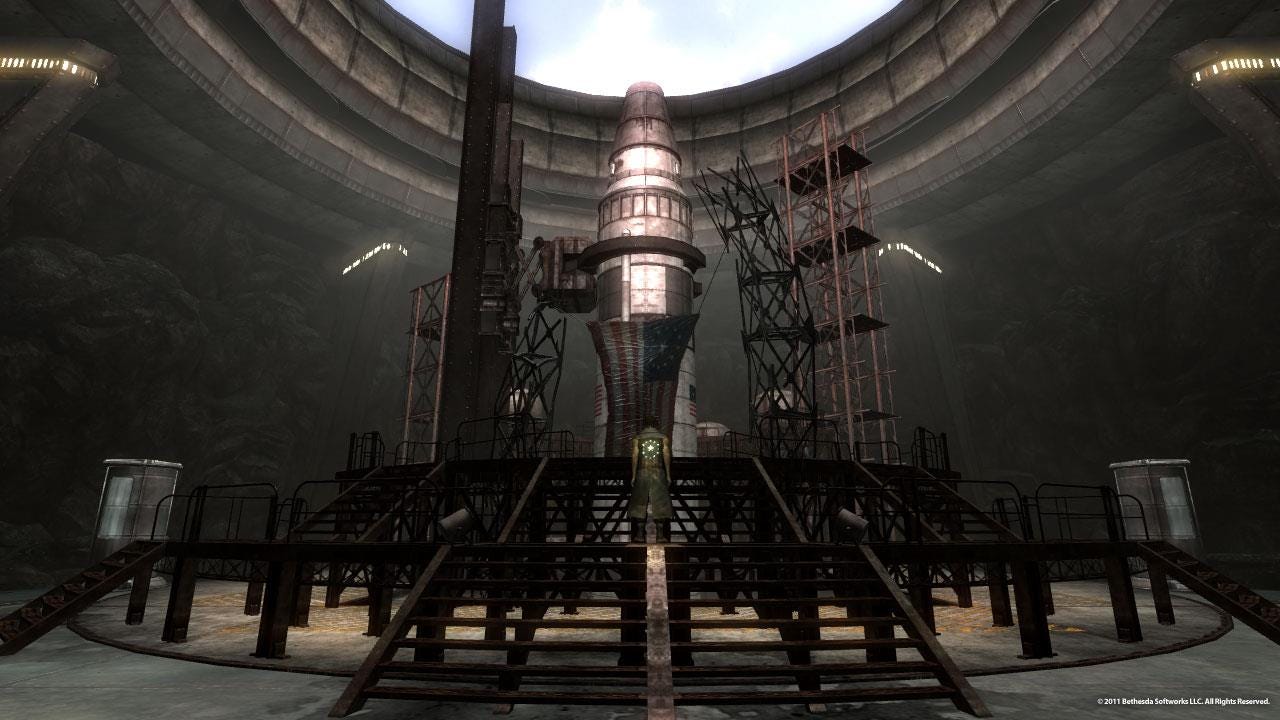

Next in the titular DLC, "Old World Blues," the metaphor becomes literal. The player is abducted and awakened in the Big MT (Big Mountain Research Facility), a surreal and nightmarish parody of pre-war scientific ambition. Here, disembodied scientists (the Think Tank) continue their experiments long after their purposes have been forgotten in the ruins of America. These figures, now little more than sentient egos with voices, embody the sterility and madness of unmoored intellectualism that has defined the modern world’s obsession with progress for the sake of progress. Their obsession with science, devoid of ethics or humanity, serves as a chilling critique of Enlightenment rationalism run amok, the teleological dead end of atheism as logical insanity, as a utilitarian answer to a world without God. The player’s role is not simply to defeat them, but to mediate, challenge, and ultimately reorient their purpose towards a higher and noble goal, to let go of the Sino-American war of the Past by the creation of mad experiments, but to use science to improve this wasteland for a better tomorrow.

Finally, the "Lonesome Road" DLC ties together the philosophical journey with an existential climax. Ulysses, the antagonist, is a Courier like the player—someone who once believed in the symbols and meanings of his world. Now he sees the NCR, the Legion, and even the player’s actions as iterations of the same cycles that doomed the old world; Ulysses is chained to the nihilism of the eternal return. His desire to trigger another nuclear holocaust stems not from madness, but from a grim conviction that only through total erasure can something truly new arise and escape from the cycle of history. The player, in confronting Ulysses, is forced to reckon with their own choices and legacy. The road to the Divide, lined with broken cities and collapsed ideals, this is demonstrated by the “marked men,” insane former soldiers of the NCR and Legion who kill each other in an endless loop of madness, highlighting the failure of their ideas. The Courier caused the nuke disaster that affects the divide in a prior life, the ruin of the Divide caused by the Player character before we find them with tabula rasa blanks slate of ammenisa is symbolic of the ruin of the present, which is created by the poor decisions of past actors that we have no control over and we are forced to adapt too. In the end, the player can reject Ulysses’ nihilism, not by embracing any of the old world’s factions wholesale, but by charting a new path—independent, imperfect, but forward-looking thus the road through the Divide is a pilgrimage through the ruins of civilization, a Nietzschean hymn to become a Übermensch and rise above the chaos and chart a new path through the force of will. The battle between Courier and Ulysses is the struggle between redemption in the face of decline, that even in this dark age, a new golden age is attainable for those who shed blood to achieve it.

This is the genius of Fallout: New Vegas. It understands that nostalgia, while emotionally potent, is also politically and spiritually dangerous. The game does not ask the player to restore the old world, but to learn from its ashes. In a setting littered with the detritus of lost greatness, New Vegas calls upon the player to become a figure of transvaluation—someone who confronts old world blues not with longing, but with clarity. The future lies not in reclamation, but in invention. To build anything meaningful in the Mojave, one must first accept that the old world is truly dead. Only then can one “begin again” must “let go” to return to Vera Keyes’ tagline in Dead Money. In this way, Fallout: New Vegas becomes more than a post-apocalyptic adventure. It is a meditation on civilizational death and rebirth. It challenges the player—and, by extension, the society that plays it—to ask not "How can we bring back the past?" but "What must we become in order to survive the future?"

Section 2: The Historical Trajectory of the West

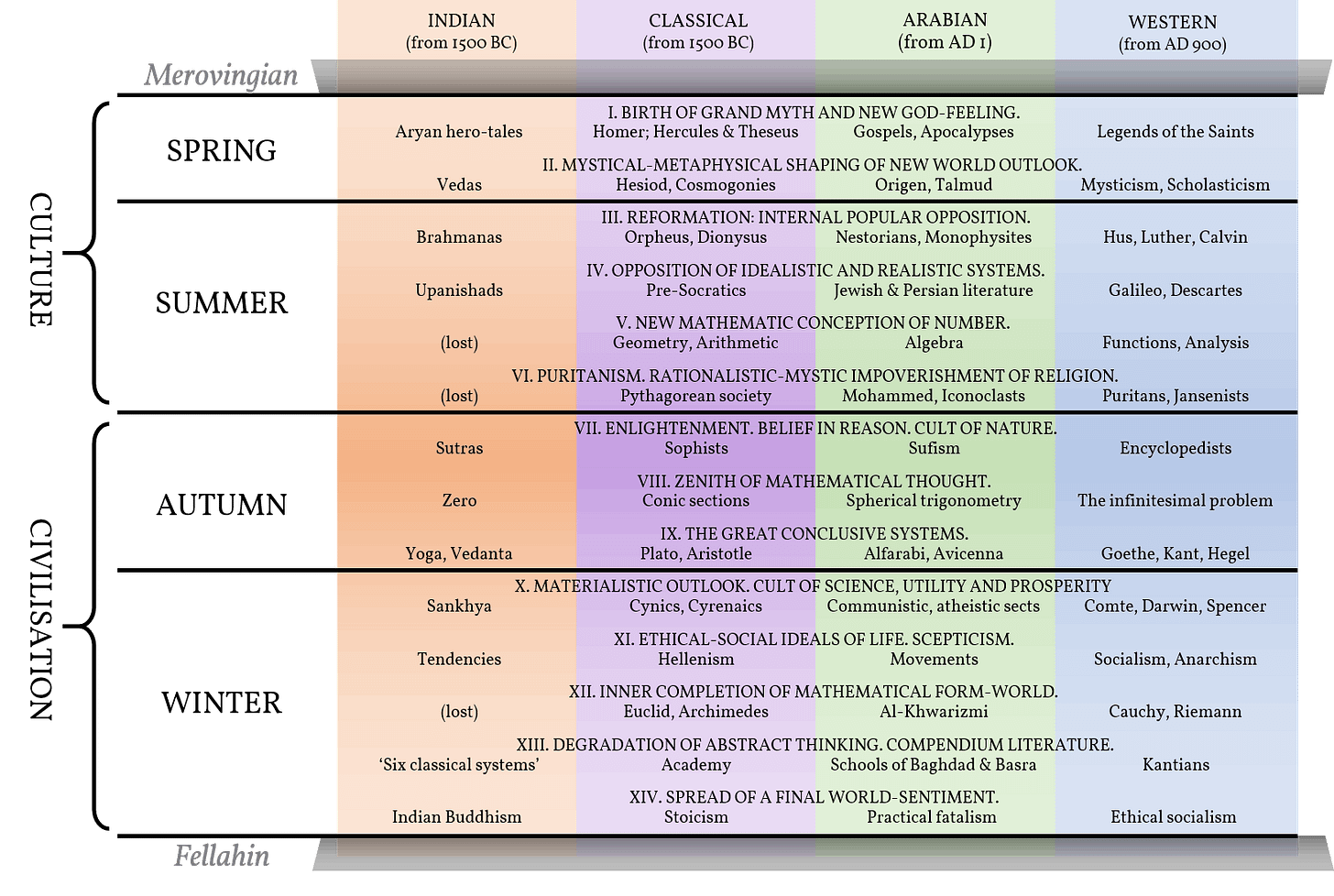

To understand the significance of "Old World Blues" in a real-world civilizational context, we must examine the West not as a static culture but as a living organism with a discernible life cycle. Oswald Spengler's seminal work, The Decline of the West, Spengler argues that cultures, like living beings, experience organic stages of birth, maturity, decline, and death. According to him, Western (or Faustian) civilization emerged around the 10th century and reached its cultural maturity in the Early Modern era. From there, it moved through the Baroque and Enlightenment periods and is now, in Spengler’s view, in its late "civilizational" phase or winter period—a time characterized by technological dominance, soulless bureaucracy, and spiritual exhaustion.[1] The West was not always the commercial, technocratic entity we see today. Its early springtime phase was steeped in a deep yearning for the infinite. The Gothic cathedrals stretching skyward, Dante's mystical poetry, and Aquinas's scholastic rigor were the traditional manifestations of the Faustian spirit—an infinite drive toward transcendence, toward mastering both the material and metaphysical realms. This was a world where the spiritual was not divorced from the political, where art, religion, and philosophy were woven into a coherent cultural fabric. However, with the Protestant Reformation and the Scientific Revolution, the trajectory of the Faustian soul began to shift. The Reformation fragmented the religious unity of Christendom and replaced the vertical spiritual hierarchy with individual conscience. This was both liberating and destabilizing. Where once the Church had served as the universal anchor of moral and metaphysical order, the new pluralism sowed the seeds for relativism. The Scientific Revolution, meanwhile, replaced metaphysical questions with empirical ones; the universe became a machine, not a mystery. With the Enlightenment, reason supplanted faith as the dominant epistemology, and with this shift came a profound change in cultural psychology. The French and Industrial Revolutions brought further upheaval. The rise of liberalism, capitalism, and secular nationalism transformed the West from a culture of spiritual inquiry and artistic transcendence into a civilization of utility and mass production. The state replaced the Church; markets replaced communities. Human beings were increasingly seen not as souls, but as economic units. Spengler saw this transition not as progress, but as a sign of decline: the shift from culture to civilization—a phase in which creative energy wanes and is replaced by rigid institutions, technical mastery, and spiritual inertia.[2] The 20th century only accelerated this process. Two World Wars, the rise and fall of totalitarian ideologies, and the omnipresence of American consumer culture created a world where the West became more of a geopolitical bloc than a coherent spiritual or cultural force. The great artistic and philosophical traditions of the past are preserved in museums and universities, but their living essence is lost. Traditions are no longer lived—they are studied, commodified, or parodied. In this sense, modern Western civilization began to mirror Fallout’s Mojave: a ruin populated by factions attempting to revive, reinterpret, or control fragments of a lost world lost in the nostalgia of Old World Blues.

Numerous contemporary thinkers endeavoring to “save the West” assume that it is still in a growth phase. They shift the focus from root causes to secondary causes, fostering the illusion that the West has only veered off track, as though we remain in the cultural context of the West in 1200 or 1700 AD. However, if we accept Spengler’s analysis, the West is not misdirected it has been detoured; it is exhausted. Like the NCR in New Vegas, modern Western states continue to expand, regulate, and campaign for democratic ideals, but they do so without the internal cohesion or vitality that once gave those ideals life, as Julius Evola in his work Revolt Against the Modern states,

The reader will have to acknowledge that the transformations and the events the West has undergone so far are not arbitrary and contingent, but rather proceed from a very specific chain of causes. I am not espousing the perspective of determinism since I believe that in this chain there is no fate at work other than the one that men have created for themselves. The “river” of history flows along the riverbed it has carved for itself. It is not easy, however, to think it possible to reverse the flow when the current has become overwhelming and all too powerful.[3]

Indeed, much of what passes for Western identity today is a simulation—what Jean Baudrillard would call a simulacrum. What is the West today? Is it a geographical entity? A set of Enlightenment values? A loose collection of military alliances and liberal democracies? Or is it something more profound: a spiritual tradition that has lost its animating soul? Multinational corporations adopt the aesthetics of tradition to sell products. Political parties invoke classical liberalism or Christian values without understanding or embodying their substance. Universities teach Plato and Aquinas, but often from a postmodern lens that strips them of metaphysical significance. Even the Catholic Church—once the beating heart of the Western spiritual order—now resembles a crumbling bureaucracy more concerned with public relations than with shepherding souls. The West has become, in Nietzschean terms, a culture where the God of its metaphysics has died, and yet its institutions continue to operate as though He were still alive. This is the real-world Old World Blues: a longing not just for the aesthetic trappings of the past, but for the spiritual coherence that gave those forms meaning. We live among the ruins of cathedrals, both literal and metaphorical. Like the characters in New Vegas, many Westerners now grasp at fragments of tradition, of nationhood, of religion—not to build something new, but to feel connected to a past they cannot fully comprehend or restore. This is why so many turn to political messiahs, conspiracy theories, or radical ideologies. They are trying to resurrect the dead with incantations that no longer work, as Evola states

Today, these conditions do not exist. Man, like never before, has lost every possibility of contact with metaphysical reality and with everything that is before and behind him. It is not a matter of creeds, philosophies, or attitudes; all these things ultimately do not matter. As I said at the beginning, in modern man there is a materialism that, through a legacy of centuries, has become almost a structure and a fundamental trait of his being. This materialism, without modern man being aware of it, kills every possibility, deflects every intent, paralyzes every attempt, and damns every effort, even those oriented to a sterile, inorganic, artificial construction.[4]

Yet the danger is not only in nostalgia, but in the refusal to accept cultural death. As with Father Elijah or Ulysses in Fallout, the temptation is to impose order through force or to destroy the world again in a fit of nihilism. But there is another path that thinkers like Julius Evola suggested: a return not to the past itself, but to the eternal principles that undergirded it. This means recognizing that while the Western world as we knew it may be physically dying and is functionally dead in spirit, the values of heroism, transcendence, family, hierarchy, and spiritual striving need not die with it. The historical trajectory of the West reveals a movement from unity to fragmentation, from mystery to mechanism, from soul to system. To confront this trajectory honestly is not to despair about what has been lost and give in to Old World Blues, as we cannot go back, but to clarify our position for the future. Just as the Courier in New Vegas must choose among flawed factions or forge their own path, so too must we decide whether to continue playing the broken game of liberal modernity or begin again, rooted in tradition but not enslaved by it. Only by acknowledging that the old world is gone and abandoning the childish notion that some politician or policy can save the West from its self-imposed cancer can we begin cultivating something new, something real, and perhaps something eternal.

Section 3: Beyond the Ruins — Overcoming Old World Blues

To move beyond the mental paralysis of "Old World Blues," both the narrative condition in Fallout: New Vegas and the real-world psychological trap gripping modern Western consciousness require more than critique. It requires vision. It requires a genuine confrontation with loss, and then, paradoxically, a rebirth not in the image of the past, but from its ashes. Where Fallout gives the player the option to side with the old, flawed powers or forge an independent future, our task is more difficult: we must forge a spiritual and cultural renaissance amid the ruins of the postmodern world. But the first step remains the same: we must let go. Letting go does not mean forgetting. It means ceasing to worship the dead, accepting the fact that the West, whether of 1000 AD, 1789 AD, or 1945, is gone and cannot be saved. It means accepting that many of the institutions, customs, and even symbols of the West are no longer what they once were. We must bury the mummy of Western culture, not drag it into battle. The Catholic Church, once a bastion of metaphysical unity, is today largely bureaucratic, fragmented, and subservient to political and social trends antithetical to its original mission. Modern academia no longer cultivates wisdom but manufactures ideology and debt. Western democracy, once a dynamic system of civic participation, has calcified into a cynical ritual of managed decline. To cling to these forms is not traditionalism; rather, more grimly, it is selfish necromancy. The postmodern West is a civilization without essence. It is not merely in decline; it is haunted by its former self. Symbols are hollowed out, rituals emptied, holidays commercialized, and values relativized. The average person in the West cannot articulate what it means to be Western beyond vague notions of freedom, rights, or consumption. Contrast this with the clarity of identity possessed by a medieval knight, a Renaissance philosopher, or a monastic ascetic. Their lives were embedded in a metaphysical structure; they saw themselves as part of a cosmic order. The Faustian man sought the infinite through architecture, theology, conquest, and science. Today’s Western man, shaped by algorithmic media and deracinated education, seeks only distraction from a world of declining standards of living.

To overcome Old World Blues is not to seek a political solution; it is to engage in metanoia, a spiritual turning. It requires a rejection of the simulacra that has been the defining modality of the West since 1945 and the courage to build anew from metaphysical first principles. As Nietzsche wrote, the death of God has left us with the burden and responsibility of creating new values. But those values must not be arbitrary or manufactured. They must be drawn from perennial truths, from the deep well of myth, metaphysics, and cosmic order that sustained civilizations for millennia. We must return to an organic way of being—a world of rootedness, hierarchy, transcendence, and duty. In a sense, the Übermensch is the hero or the priest at the end of the prior era who fills the role of God in a Godless age and, through transvaluation of values, creates a new metaphysical reality for a new age, as Nietzsche in The Gay Science states,

Does not empty space breathe upon us? Has it not become colder? Does not night come on continually, darker and darker? Shall we not have to light lanterns in the morning? Do we not hear the noise of the grave-diggers who are burying God? Do we not smell the divine putrefaction? - for even Gods putrefy! God is dead! God remains dead! And we have killed him! How shall we console ourselves, the most murderous of all murderers? The holiest and the mightiest that the world has hitherto possessed, has bled to death under our knife, - who will wipe the blood from us? With what water could we cleanse ourselves? What lustrums, what sacred games shall we have to devise? Is not the magnitude of this deed too great for us? Shall we not ourselves have to become Gods, merely to seem worthy of it? There never was a greater event, - and on account of it, all who are born after us belong to a higher history than any history hitherto![5]

This is transvaluation of values is not reactionary nostalgia rather it is the rejection of sentimentality for sociological and metaphysical virility. This path is what Evola called the "revolt against the modern world"—not through LARPing knightly feudalism or the Roman Empire, nor emulating outdated and failed political systems like fascism or communism, but through embodying the eternal warrior ethos, the initiatic principle, and the sacred order of the cosmos. Just as my personal Mithraism and Platonism are not mere historical curiosities or to larp in the Old World Blues of Greco-Roman civizlation, but as worldviews that are grounded in the cosmic participation and initiatic transformation of the Indo-European tradition of the Bronze age that hold the key foundational truths that can be built upon, the same well that the Greeks, Romans, Persians, and medieval Europeans drew water from. So too we must draw from the perennial well of tradition and participate in the light of the eternal and authentic archetypes that can be used as the template for a new high culture, drawing from the sacred without becoming a mere statement of reactionary antiquarianism. As Evola puts it, it must live, breathe, and grow as the return to tradition as the only path forward.

West needs to return to tradition in a large, universal, unanimous way that encompasses every form of life and of light; in the sense, that is, of a unitary and order that may rule supreme over every man, in every group and people in every sector of existence. I am not referring to tradition in an aristocratic and secret sense, as the deposit entrusted to a few or to an elite acting behind the scenes of history. Tradition has always existed in this subterranean sense and it still exists today; it will never get lost because of any contingency affecting the destinies of people. And yet the presence of Tradition in this sense has not prevented the decline of Western civilization. Somebody has correctly remarked that Tradition is a precious vein, but only a vein. There is a need for other veins; besides, all the veins must converge, although only the central and occult vein dominates by going underground ! Unless the right environment is present, there is no resonance. If the inner and outer conditions that allow all human activities to acquire again a meaning are lacking; if the people do not ask everything of life and by elevating it to the dignity of a rite and an offering do not orient it around a nonhuman axis then every effort is vain, there is no seed that will bear fruit, and the action of an elite remains paralyzed.[6]

What does this look like in practice? It means reclaiming the household as the center of life, not as an economic unit, but as a spiritual community. It means building real communities, not virtual networks, but of fraternities, local guilds, temples, rites of passage. It means creating art that is beautiful, symbolic, and transcendent—not ironic, nihilistic, or mass-produced. It means forming children not into consumers or activists, but into heroes, philosophers, and saints. And above all, it means the cultivation of the self as a sacred vessel—the soul as temple, the will as sword, the intellect as the torch.

To begin again, as Dead Money’s motif implores, is not to reassemble the shattered cathedral from its rubble, but to consecrate new ground and raise a new structure upon it. This requires mourning. It requires facing the reality that the West, in its high cultural forms, may be gone forever and being used as a skin suit by American Imperialism. But it also requires faith, the faith that the soil is still fertile, that new seeds can take root, and that the eternal can find new expression, just as Medieval Europe replaced Greece and Rome, a new expression can and must replace the West. Just as the player in New Vegas is not defined by the factions but by the choices they make amid the wreckage, so too are we defined not by the institutions that failed, but by the culture we are willing to birth, as Evola states,

Let us leave modern men to their “truths” and let us only be concerned about one thing: to keep standing amid a world of ruins. Even though today an efficacious, general, and realizing action stands almost no chance at all, the ranks that I mentioned before can still set up inner defenses. In an ancient ascetical text it is said that while in the beginning the law from above could be implemented, those who came afterward were only capable of half of what had been previously done; in the last times very few works will be done, but for people living in these times the great temptation will arise again; those who will endure during this time will be greater than the people of old who were very rich in works.[7]

This task is monumental. It is lonely, often without reward or recognition, and many will stand in our way out of malice and fear of a world beyond the familiar comfort of our current ruin. It is lonesome, in the most profound sense—like the road through the Divide walked by Courier Six, strewn with the ruins of better times. But it is also sacred. For those who walk, it carries within them the fire of a new dawn. This is not fantasy. This is a necessity. The liberal order is crumbling; its institutions are unsustainable. The failure of globalism, demographic collapse, ecological crisis, vapid culture, and spiritual alienation are not challenges that can be met with policy reforms or new parties. They are symptoms of a deeper collapse: the loss of a shared worldview. The next civilization will be built not by policy papers, but by myth. Not by debates, but by liturgies. Not by slogans, but by symbols. We are not victims of history, nor is this the end of history, but we are its continuation in the eternal return. Thus, we must not ask how to save the West. We must ask how to give it a funeral worthy of its greatness—and how to use its bones to fertilize the earth. Out of those bones, a new culture may grow—not a replica or Old World Blues, but a new world fire. We do not need another Rome or another America. We need something greater: a civilization born not of nostalgia, but of necessity; not of decadence, but of destiny. And for that, we must be both mourners and builders—carrying the wisdom of the dead and the flame of the yet-to-be. This is the fulfillment, not the negation, of the best of the West. Not the Enlightenment, but the Logos. Not modern rights, but eternal duties. Not GDP, but glory. The soul of the West may not live—not in its current institutions, but in the men and women willing to embody its spirit, its will to power anew.

Conclusion: The Path of Fire is to Begin Again

Fallout: New Vegas begins in the ashes of a lost world, just as we find ourselves standing amid the smoldering ruins of Western civilization. In that game, as in this age, the player must make a choice: to serve one of the dying empires clinging to relevance or to navigate a solitary and uncertain path toward revival. The game ends not with a neat resolution, but with an open future. So too must we end this reflection—not with despair, nor with sentimental longing, but with resolve. Old World Blues transcends mere nostalgia; it embodies a form of psychic paralysis and a refusal to mourn. It represents a spiritual attachment to outdated practices that no longer offer vitality. To transcend this state is not to reject tradition, but to truly inherit it: embracing its essence rather than clinging to its remnants. This is the burden of the Faustian individual—not to dwell in sorrow but to create anew. Spengler alluded to this when he discussed the natural and cyclical rise and fall of cultures. Likewise, Evola urged us to rise against the modern world—not out of bitterness, but in the spirit of transcendence. The West, as we once knew it, is gone. Yet, the faint glow of its essence emanates from the past—its sacred geometry, philosophical depth, and heroic spirit can be revived. Not through globalist democracies, decaying structures, or ideological battles, but through the vibrant passion of those who dare to reshape the world. We seek not to salvage the West as a crumbling relic pretending to be a glorious epoch. Instead, we must surpass it. We must step away from the vacant cathedral and erect a new temple, with foundations that are eternal and spires that reach for the divine. This new world will not be easy. It will be forged through hardship, sacrifice, and deep solitude, as Evola states,

This is all we can say about a certain category of men in view of the fulfillment of the times, a category that by virtue of its own nature must be that of a minority – This dangerous path may be trodden. It is a real test. In order for it to be complete in its resolve it is necessary to meet the following conditions: all the bridges are to be cut, no support found, and no returns possible; also, the only way out must be forward. It is typical of a heroic vocation to face the greatest wave knowing that two destinies lie ahead: that of those who will die with the dissolution of the modem world, and that of those who will find themselves in the main and regal stream of the new current. Before the vision of the Iron Age, Hesiod exclaimed: “May I have not been born in it!” But Hesiod, after all, was a Pelasgic spirit, unaware of a higher vocation. For other natures there is a different truth; to them applies the teaching that was also known in the East: although the Kali Yuga is an age of great destructions, those who live during it and manage to remain standing may achieve fruits that were not easily achieved by men living in other ages.[8]

Yet it will be authentic. It will be genuine. It will be sacred. Like the Courier entering the Divide, we venture forth alone, yet not without intention. With trust in the divine, commitment to truth, and passion in our hearts, we begin again. Like the Courier in the Mojave, we do not begin with power, but are shot in the head, wounded by the modern world. We are men among the ruins, picking through the waste for meaning and armed only with choice, the Courier forges a new world by his will to power and seeks the heroic path. The road is long, lonely, and dangerous. Nonetheless, it belongs to us, the vanguard of the new dawn.

Bibliography

Fallout: New Vegas by Obsidian Entertainment, 2010

Friedrich Nietzsche: The Gay Science

Oswald Spengler’s Decline of the West, Volume 1, and Man and Technics

Julius Evola, Revolt Against the Modern World

[1] Oswald Spengler, Decline of the West, Volume 1, 46-8. Man and Technics, 61-78.

[2] Man and Technics, ibid

[3] Julius Evola, Revolt Against the Modern, 358.

[4] Evola, 359

[5] Friedrich Nietzsche - The Gay Science Book III - Aphorism # 125

[6] Evola, 359

[7] Evola, 364-5

[8] Evola 366