Mithra, The Hidden Sun of The Aryans Part 4: Roman Mithraism

A Historical Study of the Roman Mystery of Mithra From the Pax Romana to the Fall of The Western Empire

The study of Mithra, as examined throughout my Substack, has assessed the anthropology of a God and his cultural interactions with various Indo-European peoples from the Bronze Age forward. This will be the first in a series of papers examining multiple aspects of the Mithraic Cult during the Roman Empire. Yet, this is the conclusion paper in my series on the History of Mithras explaining the most famous incarnation of the Mithra, the Roman Mystery of Mithras. The Roman Cult of Mithras flourished from the Pax Romana to the Collapse of the Western Roman Empire. The history of Roman Mithraism was born from Roman contact with the Hellenistic astral Mithra religion, which was created in the city of Tarsus and diverged significantly from its Persian origins. The Mithraic religion, as concluded in my last paper, began to spread across the Roman world with the movement of soldiers, slaves, and merchants after the defeat of Mithridates VI and the conquest of Tarsus and the Kingdom of Commagene resulted in Mithraic beliefs in the eastern provinces being brought back to Rome,[1] as Jason Reza Jorjani states in as Iranian Leviathan: A Monumental History of Mithra’s Abode,

Mithraism was the dominant religion within the Roman military, and a few Caesars were even counted among its initiates. Roman centurions were stationed in places other than their region of origin and moved often so that any one legion of them was a microcosm of the empire. Besides recruiting centurions from territories governed by the Parthians, the Romans occasionally recruited defeated Parthian cavalry into their own ranks. These recruits formed brotherhoods to preserve their Mithraic religion, and owing to the humanistic character of Mithraism, these brotherhoods were open to their fellow Roman soldiers, men who no doubt found the mysteries of the Orient alluring — especially when the god in question was believed to secure martial victory. When these converts were transferred, they recruited others to the faith in a realm of Roman military power extending from the Black Sea to the Scottish Highlands and the Sahara desert. Aside from the Cilician pirates, there were Mithraic initiates in the Roman Navy itself, and these spread Mithraism across Europe through the river systems that ran through Rome’s continental empire. No less than 420 Mithraea have been unearthed from the Middle East to northern England.[2]

Jorjani contends that Parthian cavalry was the vector of transmission of the Mithraic faith amidst the legion. Among the Roman army's cavalry and archers auxiliaries, evidence shows there were followers of Mithras. Mithras, known as the invincible protector of archers, was seen as a divine archer who could release water from dry rocks with arrows.[3] A Roman relief even depicts him holding a bow from birth. Additionally, Mithras was seen as a Rider-god whose precise aim never missed his targets, whether a gazelle or a wild boar.[4] Until the Muslim Conquest, Rome would recruit specialists from oriental cultures like Iranians, Armenians, and Syrians as auxiliaries who excelled at archery and horsemanship. Therefore, since these types of specialties auxiliary units were rotated around the empire, Jorjani’s idea that Iranian auxiliary units could have served on every frontier from Britain to the Sahra and from the Rhine to the Danube rivers and influencing the native legionaries and officers alike to the heroic warrior theology of the Iranian Solar God Mithra.

The intersection of Mithraism in Roman history after the deportation of Mithraic cultists and Cilician pirates after the Mithridatic wars by Pompey Magnus to Greece and Southern Italy, we start to see the start of the cult slowly gaining ground through the legion. The Roman military, through these oriental auxiliaries, was the memetic vehicle that spread Mithra across Roman society across the social stratum from slaves to Emperors. However, the cult, given its martial nature, was exclusively male and built a military fraternal order that united all men, overcoming social and ethnic lines by the Aryan idea of the cosmic oath, or what the Hindus called Rta, [5] as Jorjani states,

Members of a Mithraic secret society were bound together by oaths of loyalty that demanded greater devotion to one another than to their own kin, and the soldiers — or pirates — who became initiates were often far away from their families and even from their native country. In this case, water was actually thicker than blood.[6]

This new Mithraic religion would spread beyond the Empire’s military as Mithras infiltrated his way onto the Capitoline Hill, the home of the Julio-Claudian Dynasty. Emperor Nero was the first historically recorded emperor to be initiated into the Mithraic cult by King Tiridates I, the newly installed king of Armenia, in 66 CE. As Pliny the Younger states,

The Zoroastrian magus Tiridates came to celebrate Nero’s conquest over Armenia, and he brought with him other magi. And he even went so far as to initiate the Emperor in the repasts of the craft, but even though he had received a kingdom from him, wasn’t able to make Nero a magus.[7]

Carl A. P Ruck, in his book Myths & Mithras: The Drug Cult that Civilized Europe, argues that this ritual was a “magical dinner” defined by the consumption of Amanita muscaria-infused wine and blessed bread. [8] Nero believed he was a living avatar of Mithras, as seen by how “He also installed an enormous statue of himself in his Golden House as the Sun God.” [9] The premature death of Nero seems to have pushed the Mithras cult out of the focus of history. However, an exciting and controversial tangent is the recent scholarship of Attilio Mastrocinque in his book The Mithraic Prophecy, which argues that the 4th Eclogue of Virgil tells of a prophecy hailing the coming morning star who is Mithras (rather than Jesus as many Christians claimed) would bring a new Golden age to the civil war-ravaged Roman world. Mastrocinque explains that Virgil was part of the First Emperor’s court. Still, Virgil produced the Aeneid that hails the divine coming of Augustus as restoring the Roman Monarchy of Aeneas and Romulus. The idea of Augustus connected to the cult of Mithras is not as controversial claim as it may appear; the first Emperor was attached to the Tarsus Stoic academy (the originators of the Hellenic Mithra/Perseus cult) via the philosopher Athenodorus as D. Jason Cooper, in his book Mithras: Mysteries and Initiation Rediscovered, states,

It is likely that even as early as Augustus the military included initiates. In 45 BCE. Augustus himself met the great Stoic philosopher Athenodorus Cananites from Anatolian Tarsus, a hotbed of Mithraism. He brought him to Rome, where he stayed as an advisor until 15 BCE, when the philosopher returned to his native city to reform its constitution. It would be highly unlikely that the two never discussed philosophy or religion. In fact, Augustus styled himself as the putative son of Apollo and once officiated at a sacramental meal dressed as the Sun with twelve of his colleagues costumed as the signs of the zodiac.[10]

This Apollonian idealism of the Emperor fits Virgil’s prophecy of a new Solar figure who would defeat the Titans and create a new golden era of peace. Interestingly, Augustus saw himself as the agent of Apollo, much like his descendant Nero, who considered himself an avatar of Mithras. Perhaps the Apollonian symbolism of the Julio-Claudian dynasty is a hint at cultic worship of Mithra by the first Emperor and his family, and possibly Nero’s initiation by Tiridates was reaffirming of the Imperial family loyalty to Mithraism by the reintroduction of the Persian elements of the Cult? This topic of Mastrocinque and the prophecy of the 4th Eclogue of Virgil in a Mithraic apocalypse that gave the theological justification that legitimized the birth of the Empire and the Pax Romana will be examined further in a future paper. After Nero, the trail of the history of Mithras in the Roman Empire goes cold. Being a mystery cult with no public historical records makes the job of history difficult. However, we have references that Emperor Vespasian and his legions seem to have adopted the worship of a solar deity from their time in the east as seen during the Year of the Four Emperors, as Tacitus relates,

It was an ancient custom among the soldiers of Vespasian’s legions, whenever they rose, to salute the rising sun, and now their homage to this luminary was turned into an omen of empire.[11]

What was this oriental solar god? Was it Mithra or the Semitic god Shamash? It’s hard to say, but it shows that the solar deities were becoming popular, with legions serving in the east during the High Imperium. What we can say for sure is that, as mentioned earlier about the rotation of original auxiliary units around the empire, we can see that “under the Flavians, the indigenous alæ or cohorts formed but a minimal fraction of the auxiliaries that guarded the frontiers of the Rhine and the Danube.”[12] Hinting at the process of Mithraic dissemination may have been underway during the Flavian dynasty. Initially a minor and marginalized deity worshipped by displaced Asians from the Orient, Mithras gained followers from the lower social strata. Notably, Mithraism was initially associated with the lower classes for a long time, as evidenced by inscriptions from slaves, freedmen, and soldiers, both active and retired. Freedmen, who could rise to significant positions within the empire, and the descendants of veterans or centurions often achieved wealth and influence. During the era of the Pax Romana, Mithras transitioned from relative obscurity to become a prominent deity among the Roman aristocracy, and “The Roman imperial court continued its official practice of Mithraism for 300 years”[13]. Consequently, as Mithraism established itself in Roman society, it naturally grew in wealth and influence, eventually attracting influential figures, including high-ranking officials and local dignitaries.[14] However, this was not a mass public worship nor enforced by the state. Yet the cult of Mithra by the time of the reign of Antoninus Pious was gaining traction with the intelligentsia and aristocracy of the Empire as Franz Cumont, in his magisterial work The Mystery of Mithra, states

Under the Antonines (138-180 A.D.), literary men and philosophers began to grow interested in the dogmas and rites of this Oriental cult. The wit of Lucian parodied their ceremonies; and in 177 A.D. Celsus in his True Discourse undoubtedly pits its doctrines against those of Christianity. At about the same period a certain Pallas devoted to Mithraism a special work, and Porphyry cites a certain Eubulus who had published in several books. If this literature were not irrevocably lost to us, we should doubtless re-read in its pages the story of entire Roman squadrons, both officers and soldiers, passing over to the faith of the hereditary enemies of the empire, and of great lords converted by the slaves their own establishments. The monuments frequently mention the names of slaves beside those of freedmen, and sometimes it is the former that have attained the highest rank among the initiates. In these societies, the last frequently became the first, and the first the last,--to all appearances at least.[15]

This was when the Platonic school, with philosophers like Celsus and Apuleius, started integrating Mithraic ideas into Platonic philosophy that would culminate with the Platonic philosopher, Mithraic priest, and Roman Emperor Julian.

During the Pax Romana, the cult of Mithras was brought back into the light of historical records by another unfortunate Emperor, Commodus. Commodus, who is lumped in with some of the worst emperors yet, is, according to some new research, perhaps not as bad as we once thought. Traditionally, sources from the senatorial class have been pessimistic about him, casting him as a mad tyrant, but a revisionist historiography of Commodus is not my purpose. Instead, I make this distinction as Commodus seems not to be an insane ruler as traditional sources relate, but a revolutionary statesman for starting the trend that the Emperor was a divine figure in public settings by claiming himself the avatar of Hercules and Mithras. A facet of imperial propaganda that was mocked in his day but was vindicated in later eras of the Empire was the idea the Emperor was a living God or the vicar of Christ in the Late Empire, Byzantium, and Medieval Europe. This idea got its start with Commodus’ proclamations of Godhood, as Cumont relates,

To-ward the end of the second century, the more or less circumspect complaisance with which the Cæsars had looked upon the Iranian Mysteries was suddenly transformed into effective support. Commodus (180-192 A.D.) admitted among their adepts and participated in their secret ceremonies, and the discovery of numerous votive inscriptions, either for the welfare of this prince or bearing the date of his reign, gives us some inkling the impetus which this imperial conversion imparted to the Mithraic propaganda.[16]

Commodus's reign was full of Mithraic symbolism, such as “commissioned a bust of himself with a Persian cap in the likeness of Mithras”[17]. This period of the late 2nd century saw the beginning of the decline of traditional Greco-Roman paganism via the failure of the Augustian reforms to rebuild traditional morality and religiosity. New ideas, such as secular philosophies such as Epicureans and the mystery cults, started growing in Rome's spiritual landscape. This included the Cult of Mithra, the worship of Isis, and Early Christianity. However, the Mithraic mysteries had a leg up on the competition by having Imperial sponsorship; as Cumont states,

After the last of the Antonine emperors had thus broken with the ancient prejudice, the protection of his successors appears to have been definitely assured to the new religion. From the first Years of the third century onward it(Mithras) had its chaplain in the palace of the Augusti, and its votaries are seen to offer vows and sacrifices for the protection of Severus and Philippus.[18]

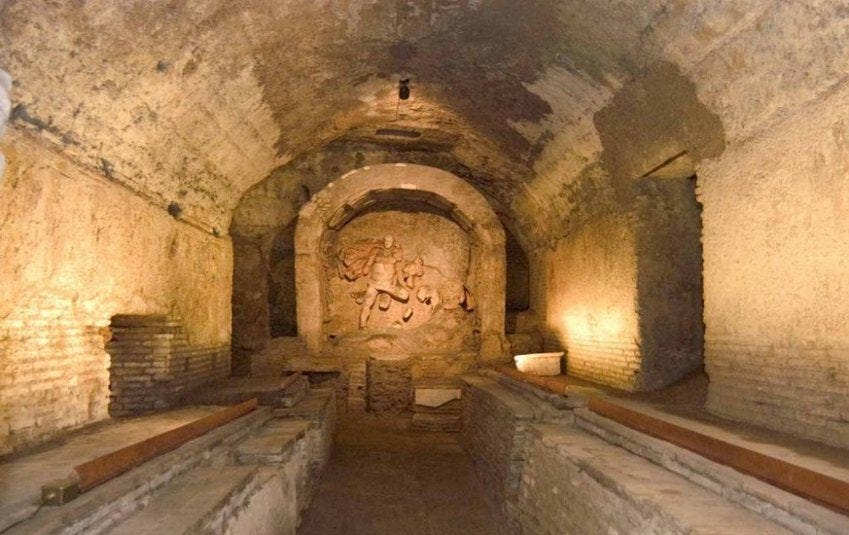

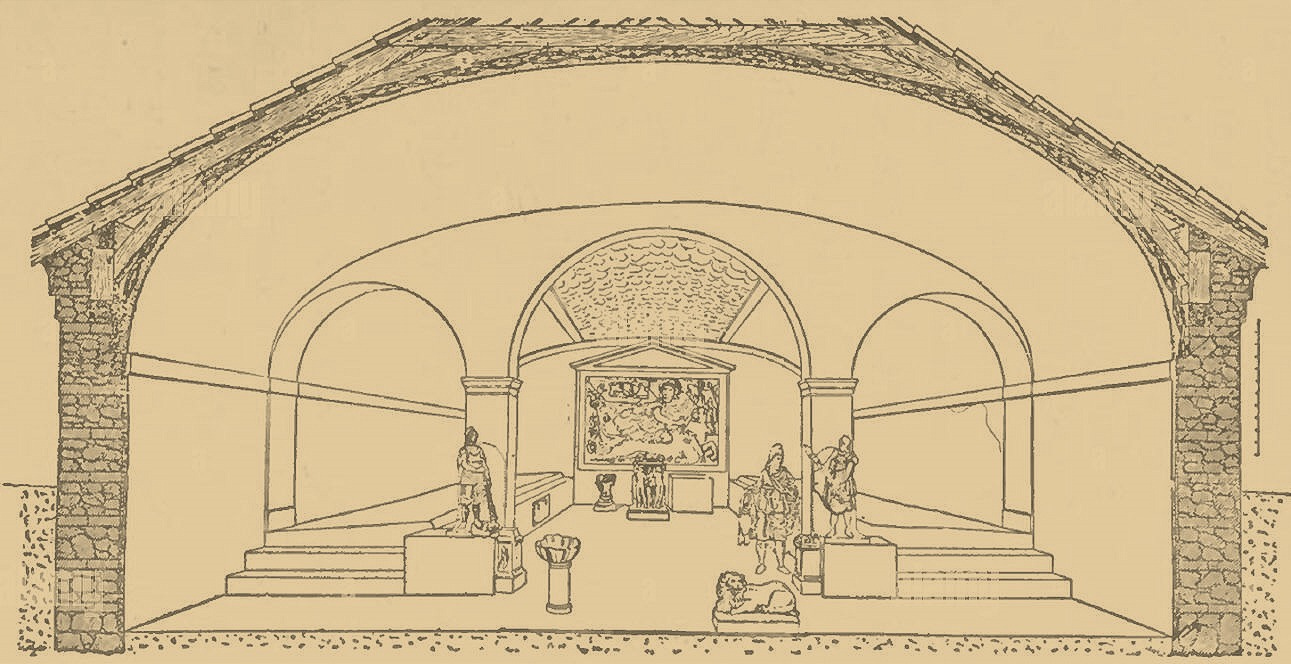

The Severan dynasty would be the following historical data point for Mithras. Septimius Severus, after his victory in a period of civil war since the assassination of Commodus, would dedicate more temples of Mithras or Mithraeums across the empire. Famously, the Emperor installed a Mithraeum in the imperial villa of Emperor Trajan on the Aventine hill in Rome,[19] leading the influential Mithraic scholar M. J. Vermaseren in his book Mithras, the Secret God to argue that it was the Severan dynasty who mainstreamed the cult of Mithras and gave it’s priesthood full imperial backing as he states, “From then on the court was won over to Mithras and a specially appointed court priest (sacerdos invicti Mithrae domus Augustanae) was in charge of the rites.”[20] This trend of the Severan dynasty of venerating Mithras would continue under the reign of Caracalla, who was like his father, an ardent supporter of the Mithraic cult. Several Mithraic temples were established in Rome during his reign, such as the famous Mithraeum of Santa Prisca and even a subterranean Mithraeum within Caracalla's famous baths. Further evidence shows that Emperor Caracalla even built Mithraeums in the African homeland of the Severan dynasty.[21]

Perhaps the reason for the rise of Mithraic worship was that by the third century, Roman emperors increasingly relied on the Legions fighting the endless civil wars. As we have the quote from Cassius Dio of Septimius Severus on his deathbed to his sons, “Be harmonious, enrich the soldiers, and scorn all other men."[22] This hints at Severus’ pragmatic view that the legionaries, not the people or the Senate were the leading power brokers in the empire. In a sense, the Crisis of the Third Century, which traditionally starts after the Severan dynasty, I would argue beginning with the fall of Commodus, Emperors from Septimius Severus to Diocletian were compelled to endorse the Mithraic faith embraced by their soldiers who had the de facto power to make or break an emperor.

The Severan dynasty laid the foundation for this feedback loop of the Emperors becoming more reliant on the Mithraic legionaries, which created a kind of Mithraic-Nietzschean struggle that defined the Crisis of the Third Century, which was brought about by the disastrous reign of Elagabalus and the overthrow of Alexnder Severus as it brought Mithraism in the form of the soldiers to panicle of political capital with the Barrack Emperors. Evidence from this time shows that one of these Barrack Emperors, Gordian III, while on route to wage war against the Sassanid Empire, minted a coin bearing the image of Mithras was struck in the provincial capital of Cilicia, Tarsus, the home city of European Mithraic faith.[23] This imperial gesture to mint a silver coin for a minor city shows particular importance; we may say that this relevance was at least confined to Emperor Gordian's Mithraic faith and thus honoring Mithras’ patron city. To be speculative, perhaps Tarsus had by the third century become a visible ritual center for Mithraic worship, or members of cults like Gordian knew the profound lore of Tarsus as the Invisible Sun’s home, which might not have been visible to your average Roman. The Crisis of the Third Century was a period of chaos where legionaries fought one another in a political state of nature where officers rose to the Imperial throne in a Nietzschean sense by violence. At the same time, these same Nietzschean Übermensch had to combat the threats of Germanic tribes, the new Zoroastrian Persian Empire, and the breakaway Gallic and Palmyrene Empires. Not to mention the active persecution of the insidious internal threat of Christianity, which seems to have been backed by the Mithraic clergy as Carl A. P Ruck, in his book Mushrooms, Myths & Mithras: The Drug Cult that Civilized Europe, states

Valerian (253-260) mercilessly purged the empire of Christians and declared December 25 the festival of the Unconquered Sun, as the days begin perceptibly to lengthen after the winter solstice. The Christians would eventually adopt this date for the birth of their god. Valerian’s son and coregent Gallienus had himself depicted as that Sol Invicta (Invincible Sun) on his coinage.[24]

The age of the Barrack Emperors would bring the blood-soaked Mithras to his apogee of power. The Third Century Crisis hardened the decaying and degenerate Roman world. Thus, this age of war was a very fitting period for a war god of Mithras’ stature, showing his Dionysian nature, as Nietzsche would say, as struggle creates a new Dionysian or Übermensch who overcomes the chaos of history and the strangulation and sterility of the overly Apollonian era as of the Principate started by Augustus. These new Übermensch, the Illyrian Emperors, beginning with Claudius II Gothicus and concluding with Diocletian, would overcome the crisis that destroyed the Pax Romana and restore a new Roman world known as the Dominate Period. These Illyrian Emperors from the 3rd and 4th centuries AD hailed from the Roman provinces of Illyricum (roughly corresponding to parts of modern-day Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia). Illyricum was a hotbed of the Mithraic cult; the province was strategically important as a critical recruiting for the legion from a hardy and warlike Illyrian population who occupied an essential border region of the Roman Empire, which facilitated the diffusion of the cult through the military via legionary vexillations networks. Cumont also relates that since the reign “of Hadrian at least (117-138 AD.), they were severally recruited from the provinces in which they were stationed. But this general rule was subject to numerous exceptions. Thus, example, the Asiatics contributed for a long time the bulk of the effective troops in Dalmatia and Moesia”[25]. Shows that the Illyrian and Pannonian Legions on the Danuban Fronter were, for 150 years, in cultural contact with probably Iranian archers and cavalrymen who would have inflected the war-like Illyrian population with the Mysteries of Mithra. This is not just my presupposition, but archeological ruins of Mithraic sites dotted the landscape, such as the defended Mithraeums like those of Rožanec, Jajce, Ptuji, Jasenovac, Salona, Sirmium, Prozor, and Močići.

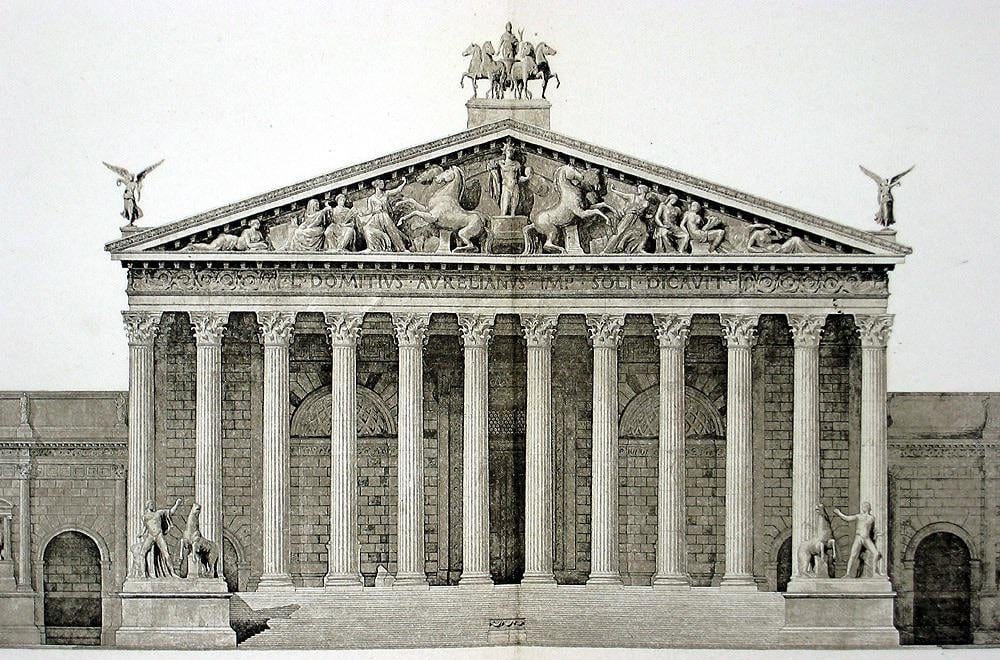

Indeed, more Mithraeum are found in the Rhine frontier in modern Germany, France, and the Roman heartland of Italy. However, I do not think it an insignificant point to be made that the Illyrian Emperors who ended the Crisis of the Third Century were natives of Illyria, a province with the importance of the Danubian frontier, warlike nature of the locals, and a focal point of Germanic and Sarmatian raids meant that the Roman army was a dominant force in the social and religious life of the region, leading to the proliferation of Mithraic faith in military camps and Roman urban centers. These Illyrian Emperors are known for their military prowess, but for our purpose, a few emperors were followers of the mysteries of Mithras. Of these men, two with overly apparent historical Mithraic connections were Lucius Domitius Aurelianus or Aurelian and Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus or Diocletian. The reign of Aurelian was the decisive figure in the list of the Illyrian Emperors, as Aurelian would play a pivotal role in stabilizing the Roman Empire. Ascending to power after a series of short-lived and contested reigns, Emperor Aurelian, renowned for defeating the Gallic Empire in the West and the reintegration of the Palmyrene Empire in the East, effectively restored the empire’s territorial integrity. However, despite his impressive military record, Aurelian would play a significant role in bringing Mithraism into the light of history as the advocator of solar monotheism as a new faith to unite the Roman Empire under a new unifying theology known as the cult of Sol Invictus as Vermaseren states,

Aurelian, who promoted the cult of Sol invictus, the invincible Sun, and raised it to the status of an official cult…The emperor himself was the representative of the Sun-god; he is dominus et deusy he is invictus, he is comes and conservator. And the same titles (‘lord and god’, ‘companion’, ‘protector’) were already in use in connection with Mithras, the invincible Sun-god, whose mysteries were predominantly astrological.[26]

Sol Invictus, while not the same as the Mithraic cult, the Cult of Sol Invictus served as a public-facing theology of the Mithraic Mysteries as Cumont states, “In 273 A.D., Aurelian founded by the side of the Mysteries of the tauroctonous god a public religion, which he richly endowed, in honor of the Sol Invictus.”[27] The Cult of Sol Invictus allowed the Mithraic mysteries to be integrated into the broader state-sanctioned cult, ensuring political stability while maintaining the spiritual depth and exclusivity of the mysteries. In another way of saying it, Sol Invictus was the exoteric tradition that unified the Roman Empire under a single solar deity, while Mithraism offered a more profound, esoteric spiritual path for initiates, as Vermaseren relates,

Aurelian built a large temple to the Sun in the Campus Martius, part of which is now the Piazza San Silvestro. There he worshipped the Sun-god as the only heavenly, almighty and divine power. It was decreed that every four years celebrations were to be held in honour of this new state god and the cult acquired a priestly college of its own. The anniversary of the Sun-god’s birth was on December 25th. Understandably the Mithraic cult took advantage of this favor.[28]

Fundamentally to Aurelian and the Roman legion, the deity of Sol Invictus was seen in a Platonic sense as shared sympathy or participation with Mithras and thus regarded as identical as Vermaseren state, “Mithras is the Sun and is one and the same with Apollo, Phaethon, Hyperion and Prometheus. The other gods merely express different aspects of the power of the sun.”[29] This idea of the figure of Sol is seen as a junior partner of Mithras but related to him can be seen via the Heliodromus grade in the mysteries, which is the last grade before Pater that represents Mithra on earth, and the Platonic philosopher and Roman Emperor Julian argues in his Hymn to the Sovereign Sun that Sol Invictus or Zeus-Helios is the physical sun or lower emanation of the actual Sun, Mithras who himself is an emanation Hypercomsic Sun of the Platonic Monad as Julian remakes,

Mithras, who is the mediator between that pure, supreme, and perfect One, and us... Helios is thus the visible image of the intellectual and divine Sun, while Mithras represents the bridge between the two worlds, as the One and the same being, both Sol and Mithras [30]

The relationship between Sol and Mithras is a solar henotheism that vises the Platonic cosmology of Henaidic participation visive Iamblichus and Emperor Julian. Therefore, Sol Invictus is the public-facing or exoteric worship of Mithras. This why I argue that Aurelian’s solar monotheism or henotheism was the mainstreaming of the Roman Mithraic cult out of the shadow of the private imperial patronage that, with Diocletian ending the Crisis period, would seemly fulfill Virgil’s Mithraic age of peace. Though ironically, this Mithraic monotheism under the Domainate era would lay the groundwork for the unity of throne and altar that would define the Christian monarchies of medieval Europe and Byzantium, as Cumont concludes on the religious reforms of Aurelian,

Aurelian (270-275 A.D.) had essayed to establish an official religion broad enough to embrace all the cults of his dominions and which would have served, as it had among the Persians, both as the justification and the prop of imperial absolutism. His hopes, however, were blasted, mostly by the recalcitrance of the Christians. But the alliance of the throne with the altar, of which the Caesars of the third century had dreamed, was realized under another form; and by a strange mutation of fortune the Church itself was called upon to support the edifice whose foundations it had shattered…Mithra had paved the way achieved without them and in opposition to them. Nevertheless, they had been the first to preach in Occidental parts the doctrine of the divine right of Kings and had thus become the initiators of a movement of which the echoes were destined to resound even “to the last syllable of recorded time.[31]

However, returning to the narrative, the tragic assassination of Aurelian put the religious narrative of Mithras out of historical focus and back to a military narrative of the Crisis of the Third Century. After Aurelian, the Imperial throne passed to a Senator named Tacitus (no apparent relation to the great historian of the same name) and then to his cousin Florianus, who was challenged by the Mithraic Illyrian clique of the Roman military led by Aurelian’s subordinate Probus. Florianus was murdered by his legionaries outside the Mithraic city of Tarsus walls rather than fighting Probus. Like Florianus and Aurelian, Emperor Probus was murdered by his mutinous soldiers and replaced by the Gallo-Roman officer Carus, who spawned a short dynasty, including his sons, Carinus and Numerian. However, the Mithraic Illyrian military clique made their final bid for power under the officer Diocles, better known as Diocletian. After Carus' short reign, he was replaced in the east by his son Numerian, who led the legions to victory against the Persians. Nonetheless, during the return trip, Numerian mysteriously died. Diocles, according to tradition, accused the Pretorian Prefect Lucius Flavius Aper of killing and hiding the body of Numerian. Diocles cut down Aper before he could defend himself, which gained the respect of the legions for the show of efficiency in resolving the apparent tyrannicide. This turn of events has led some Roman sources to believe that Numerian was murdered by the leader of the Illyrian officers, himself Diocles, and he pinned the crime on Aper.[32] Aper, whose name means boar, feeds into the legend that Diocles would gain power after slaying a boar. Was Diocles’ slaying of Aper a Mithraic ritual murder to become the ruler of the known world, mirroring Mithras’ slaying of the cosmic bull to cement his role as Kosmokrator (king of the universe)? Perhaps there’s symmetry in the symbolism given the Diocletian person's religious views and positive leanings towards Mithras and his cult, which is observable later in his reign.

Furthermore, such religious symbolism of a ritual Mithraic sacrifice in front of the Mithraic legionaries would cement his legitimacy but, as well, in a Mithraic sense, would have punished those broken oaths that bound the cult is not out of the realm of reasonable conclusions. Whatever the result may be, Diocles was crowned as Diocletian by his men and would wage the final civil war of the period by defeating and killing the brother of Numerian, Carinus, at the battle of the Margus River (285ad), finally claiming the entire Roman Empire as his own, ending the Crisis of the Third Century, started by the death of Commodus some 91 years earlier.

Diocletian could be regarded as a second Augustus for his pivotal role in ending the Third Century Crisis, much like Augustus, who ushered in the peace and stability of the Roman Empire after the chaos of the late Republic. Diocletian brought about a series of transformative reforms that stabilized the empire and laid the groundwork for its continued existence in the centuries to come. He curbed internal strife and restored centralized authority by introducing the Tetrarchy, which divided imperial power among four rulers. His military, economic, and administrative reforms were as far-reaching as those of Augustus, signaling a new era of imperial strength or a second founder of the Roman state, ensuring its survival for generations. Diocletian reforms varied from administrative, military, economic, social, and religious terms, transforming Rome into its final form.

Nonetheless, Diocletian religious reforms are our focus point in laying the groundwork for a Mithraic Roman Empire. The Crisis of the Third Century, with its endemic civil and foreign wars, economic collapse, climatic shifts, and the Cyprian plague (which could have been a hemorrhagic fever like ebola). This crisis period did not just create a demographic and cultural collapse, but the Olympian religion of ancient Greece and Rome finally broke under the pressure of a civilizational freefall. This period created a moral vacuum in Roman society, sparking what Oswald Spengler, in his magnum opus Decline of the West, called a Second Religiousness states,

Everywhere it is just a toying with myths that no one really believes, a tasting of cults that it is hoped might fill the inner void. The real belief is always the belief in atoms and numbers, but it requires this highbrow hocus-pocus to make it bearable in the long run. Materialism is shallow and honest, mock-religion shallow and dishonest. But the fact that the latter is possible at all foreshadows a new and genuine spirit of seeking that declares itself, first quietly, but soon emphatically and openly, in the civilized waking-consciousness... Second Religiousness is simply that of the first, genuine, young religiousness — only otherwise experienced and expressed. It starts with Rationalism's fading out in helplessness, then the forms of the Springtime become visible, and finally the whole world of the primitive religion, which had receded before the grand forms of the early faith, returns to the foreground, powerful, in the guise of the popular syncretism that is to be found in every Culture at this phase.[33]

Seeing this moral void, Diocletian sought to build upon the legacy of his Illyrian predecessor, Aurelian’s Solar Monotheism, attempting to restructure a neo-Olympian religion with Mithras as the new lord of the Empire. As seen during the conference at Carnuntum in 307 AD on the borders of the Roman Empire, Diocletian, along with fellow tetrarch rulers such as Galerius and Licinius, dedicated an altar to Mithras, explicitly naming him as "the benefactor of the Empire" This dedication is significant because it singles out Mithras by name, distinguishing it from the broader sun-worship associated with earlier emperors like Aurelian. At the time, Mithraism was at its height, and there were even attempts to elevate Mithras to a position of supreme honor, including efforts to install his worship as the sole god of Rome.[34] The emperors' reverence for Mithras underscored a belief that the fate of the empire, much like the destiny of individuals, was governed by the stars, with the Sun—the chief of the celestial bodies—viewed as both a protector and a decisive force in the rise and fall of rulers.[35] As a solar deity, Mithras symbolized the divine authority that safeguarded their reigns and shaped their fortunes. The Mithraic temple was unlike the Olympian religion of the Pax Romana, and classical Greece was an organized institution that was up for the task of forming a new monotheistic religion to support the new empire, which gave early Christianity a run for its money, as Jorjani relates,

…the religious influence of Mithraism in Rome was as institutional as that of the Church as it rose to power. Like Churches today, Mithraic communities were juridical bodies capable of holding property. Private benefactors would put up the cost of digging the subterranean chambers, or would volunteer their own cellars. The similarities of Mithraism to Christianity frightened the Christian writers who became aware of them, and they resorted to claiming that the devil, who had the demonic power to attain foreknowledge of the coming of Christ, had imitated elements of what would become Christianity and introduced them into the world so as to denigrate Christ’s gospel and misguide people.[36]

This ambition of Diocletian to create a new Mithraic “church” would create a spiritual conflict with early Christianity, which grew in leaps and bounds during the Crisis of the Third Century, offering salvation for the Romans who were experiencing the seeming end of their world. Therefore, Christians and, to a lesser degree, the Manicheans were obstacles to the Diocletian vision of a Mithraic church. It seems from Christian sources that Diocletian unleashed Mithraic clergy as they “were suspected of instigating his persecution of the Christians in 303 under his son-in-law Galerius Maximianus”[37]. The ambition of Diocletian for a Mithraic Empire was undone by the rise of Constantine and the coming of Christianity.

Constantine's conversion to Christianity, while pivotal in shaping the future of the Roman Empire and the spread of the faith, has long been debated as potentially more politically motivated than spiritual as he was

a worshiper of the Sun was likely a Mithraic initiate.. had dealt the cult a serious blow. The vision that precipitated his conversion indicated the superiority of Christ, for he saw a cross shining above his former god, the Sun. However, the interpretation of his imperial standard is ambiguous and can easily be seen as Mithraic, and he styled himself as an avatar of Mithras.[38]

The Chi Ro seems to have been a Mithraic symbol before Constantine's adoption, and perhaps Constantine was a Mithraist who would have been familiar with the symbol.[39] One significant piece of evidence supporting this view is his delayed baptism, which occurred only on his deathbed in 337 AD, despite his professed conversion decades earlier.[40] This delay suggests Constantine may have hesitated to fully commit to the Christian faith and its obligations while serving as emperor. Instead, he maintained a policy of religious tolerance, exemplified by the Edict of Milan in 313 AD, which legalized Christianity but permitted the worship of all religions, demonstrating his pragmatic approach to balancing religious interests in his diverse empire.[41] Another critical aspect of Constantine's reign that casts doubt on the sincerity of his conversion is his continued association with paganism. Even after his conversion, Constantine retained the title of Pontifex Maximus, the high priest of Roman paganism. He continued to mint coins featuring the Sol Invictus, a sun deity closely associated with Roman imperial power. These actions suggest that Constantine was keen to maintain the loyalty of the pagan majority, who still comprised a significant portion of the Roman populace. By blending Christian practices with familiar pagan customs, such as declaring Sunday a day of rest—traditionally dedicated to the Sun god—he ensured that Christianity became more palatable to the Roman population, a move that appears more politically astute than religiously devout.[42] Constantine's involvement in Christian theological debates and his ruthless political decisions further indicate the possibility of a politically motivated conversion. His convening of the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD, intended to resolve the Arian controversy, was primarily aimed at maintaining religious unity rather than enforcing a strict theological doctrine, showing his concern for stability over spiritual integrity.[43] Additionally, Constantine's execution of family members, such as his son Crispus and wife Fausta, demonstrates a level of cruelty inconsistent with Christian moral teachings, further suggesting that his commitment to Christianity may have been superficial.[44] These elements indicate that Constantine’s conversion, while crucial to Christianity's rise, was likely driven by a combination of political strategy and the desire to consolidate power. Why did Constantine make this radical shift from Mithraism/Sol Invictus to Christianity but did not commit fully to the conversion of the Empire like Emperor Theodosius? Jorjani boldly argues that Constantine’s decision originated with the rise of the Sassanid Empire. Ardeshir's reign was before Constantine’s lifetime but significantly impacted both Persia and Rome. Ardeshir sought to redefine Persian identity by rejecting Greek cultural influence and launched aggressive campaigns against the Roman Empire, aiming to reclaim territories lost since Alexander the Great's conquest, making the Sassanid more dangerous than the Parthians. Ardeshir turned Persia into a centralized, totalitarian, monotheistic state from the decentralized and tolerant Parthian Empire.[45] In response, the Romans adopted Christianity as a countermeasure to the Sassanid state; as Jorjani relates,

Given the national security threat from Iran, this could not be “the Persian religion” of Mithraism, and there was no pagan Greco-Roman religion structurally suitable to play such a role. So the social engineers of Constantine’s time discovered a Jewish cult that could do the job, and incorporated many Mithraic ideas, symbols, and rituals into this universalist form of Judaism so as to placate those Romans who were already Mithraists. After all, it was not as if the Jews of Roman Palestine had the capability of taking over the Roman Empire through the Roman adoption of some version of their religion, in the way that Mithraism could be used as a fifth column for a Persian takeover of the Roman Empire — one that might be followed by a replacement of Mithraism with puritanical Sassanid Zoroastrian orthodoxy… It would be concerning enough if, at a time when the Iranian religion of Mithraism was about to build a bridge between pagan Rome and Mahayana Buddhist northern India, Ardeshir’s intention was to turn Zoroastrianism into a vehicle for a kind of national unity that shields itself against outsiders. But it would hardly have escaped the notice of the cosmopolitan Romans that Ardeshir was now claiming to be the rightful ruler of the entire Aryan world, which, at that time, besides Iran, included northern India and Europe. By explicitly defining his state as Irânshahr or “the Aryan Imperium,” the founder of the Sassanian regime was equating Zoroastrianism with Aryan identity. [46]

Constantine’s adoption of Christianity, beginning with his reign in 306 and culminating in its establishment as Rome’s state religion, is contextualized as a defensive reaction to the threat of the Sassanian Empire.[47] If Jorjani’s thesis is correct, this hypothesis could explain Constantine’s tepid conversion to Christianity as a pragmatic political move to defend against Persian aggression rather than a genuine conversion of faith. Yet I shall let the reader be the judge.

Regardless of his rationale, Constantine's reign would radically change the dynamic between the Mithraic Clergy, now out of Imperial favor, and the Christian Church, now in the dominant position, in theory at least. The successive reigns of Constantine’s sons, who openly advocated for Arianism, actively undermined the council of Nicaea and, thus, Church unity. In the religious chaos, Julian, known in Christian sources as the Apostate, was born, but more accurately known as Julian II, the Philosopher. Julian was born into the Constantinian dynasty and lived as a virtual prisoner of his cousin Emperor Constantius II after he murdered many princelings from Julian’s side of the Constantinian family in a paranoid attempt to prevent usurpation. This left Julian and his brother Gallus alive, thus seeing Christianity related to the trauma inflicted on him by his cousin. After the massacre of the princes, Julian was shuffled around to different estates away from the levers of power of Constantinople. Julian used this comfortable exile to study the classics of Gerco-Roman culture. At the age of 18, free from his house arrest, Julian traveled around the Eastern Empire learning philosophy by studying under the masters of the Neoplatonic school in Athens and Ephesus under the chosen student of Iamblichus, Aedesius and then his pupil Maximus of Ephesus, who converted Julian from Christianity to a Neoplatonism.[48] Furthermore, Maximus initiated Julian into the Mithraic cult as Abbot Giuseppe Ricciotti, in his book Julain The Apostate, states, “There can be no doubt, on the other hand, that Julian was initiated into the mysteries of Mithra.”[49] Julian became a Mithraist and “in his attempt to reverse the Conversion to Christianity and revive the old pagan religions…He had a Mithraeum erected in his palace in Constantinople. Like Nero, he saw himself as the incarnation of the god Mithras. Ever since childhood, he had cherished a secret devotion to the god Helios as his spiritual father.”[50]

Julian’s Neoplatonism is heavily influenced by his Mithraic beliefs, as seen in his philosophical works, such as The Hymn to the Sovereign Sun.[51] Julian was part of a tradition of Mithraic Platonism, starting with Porphyry of Tyre, which was fervently anti-Christian, and this mentalité would guide Julian’s philosophical writing. Julian was taped by his cousin Constantius II to become his Ceasar and posted to Gaul to deal with a Germanic invasion. Julian, the assuming bookworm, led a successful Roman campaign against the Germans, defeating them at the battle of Argenteum; then, in old Mithraic fashion, the legionnaires declared Julian Emperor and usurper against Constantius. The war between cousins would never come as Constantius died, but miraculously, the Emperor named Julian his heir on his deathbed, avoiding the disaster of a civil war. Julian’s independent rule as Emperor sought to undo the religious influence of his cousin and Constantine by restarting the religious policies of Diocletian with a Platonic addition, as Ricciotti states,

For the higher offices, at least, he turned to his fellow initiates, the Neoplatonic theurgists, and the faithful followers of the god Mithra. The Neoplatonic theurgists, and the faithful followers of the god Mithra.Drawing his inspiration in part from the Church and in part from the followers of Mithra (§§ 60, 161), Julian proposed to organize the pagan priesthoods into a regular hierarchy; but this project was only in its initial stages when he died. Over the priests of a city was to be the archpriest; over the archpriests of a province was to be the pontifex maximus of the province, and at the head of the entire hierarchy was to be Julian, pontifex maximus of the empire and grand master of all the priestly corporations. And just as the higher clergy to watch over the conduct of the lower, so Julian was to have supreme jurisdiction over all.[52]

Julian’s ambition was not fully realized but was on its way to undoing the damage of Constantine (while outside the scope of this paper, Julian’s religious policy was undoing Christianity’s hold on the imperial government and had great potential of restoring Mithraic dominance, yet this a subject for a future paper). Still, after taking power, he marched east to the land of Mithra to fend off the perennial threat of Sassanid Persia.[53] The campaign in the east would claim Julian’s life at the battle of Samarra, as the Persians ambushed the Roman legion. Julian left his tent hastily to command his men to forget to put on his armor. An arrow mortally wounded him, heroically leading his men as Ruck concludes, ”He died during his expedition against the Persians, apparently desiring to conquer the land that had given him his religion, assured that his tutelary deity would grant him victory.”[54]

Julian’s death during his campaign against the Persians, who also revered Mithras, can be interpreted as a profound instance of heroic apotheosis within Roman Mithras. His demise is not merely a tragic end but a symbolic surrender to the inexorable tide of historical transformation. As a fervent devotee of Mithras, Julian’s ultimate sacrifice on the battlefield can be viewed as transcending the temporal realm, embodying the essence of Mithraic apotheosis of heroic death in battle. In this sense, his death signifies a heroic culmination, where Julian’s devotion to Mithras aligns with the deity who promises spiritual transcendence beyond the constraints of earthly life. Thus, Julian's end reflects a poignant and profoundly symbolic moment where personal sacrifice intersects with the grand narrative of Roman civilization’s decline, embodying a mystical union with Mithras that transcends historical defeat and embraces a higher, divine resolution. Julian’s death historically brings us to the end of the story of Roman Mithraism as his death of Julian ultimately created a void for the Christians to recapture the Imperial throne and thus establish cultural and religious dominance; Julian would be the last pagan, let alone Mithraic Emperor to sit on the Imperial Throne.[55] As Edward Gibbon states in his work The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, relates,

The death of Julian had left the public affairs of the empire in a very doubtful and dangerous situation…the first moments of peace where consecrated by the pious Jovian to restore the domestic tranquility of the church and state…as soon as he ascended the throne, he transmitted a circular epistle to all the governors of provinces: in which he confessed the divine truth, and secured the legal establishment, of the Christian religion. The insidious edicts of Julian were abolished; the ecclesiastical immunities were restored and enlarged.[56]

Christianity used the mechanisms of political power of the Roman government to enforce and spread Christian doctrines while simultaneously persecuting and delegitimizing opponents, such as the Neoplatonists and the Mithraic cult. The Roman state established legal codes forbidding pagan worship and outlawing of pagan rituals, such as sacrifice.[57] After the death of Emperor Julian in AD 363, a brief period of religious tolerance followed. Still, it ended in AD 382 when Emperor Gratian issued an edict removing the Altar of Victory from the Senate and withdrawing state support for Roman pagan cults. Gratian also became the first emperor to refuse the title of pontifex maximus and handed the title to Bishop Ambrose of Milian, who started the tradition of Catholic Popes. Around the same time, the city prefect of Rome, Gracchus, reportedly destroyed a Mithraic temple, possibly the sanctuary at San Silvestro, as evidenced by damage seen at Santa Prisca. Gratian also faced opposition from intellectuals, some made of Platonic and Mithraic partisans of Julian’s legacy and others who were Olympian traditionalists united in defending the Roman faith. One of their leaders, Vettius Agorius Praetextatus, the last recorded "Father of Fathers" or Pater, the leader of the Mithraic cult.[61] Alongside his friend Quintus Aurelius Symmachus, these pagan conservatives defended traditional Roman religious practices, with Verius Nicomachus Flavianus continuing the struggle and facing punishment for his actions.[62] Yet, Praetextatus and Symmachus failed to defend Roman tradition from Christian dogmatism and persecution. The Roman Empire was ensconced in its new Christian tradition and would eventually collapse in 475 AD; Christ could not halt the tide of history either.

The Mithraic cult disappeared from the historical record after the references of Praetextatus and Symmachus attempted to restore religious tolerance, hinting at violent religious persecution by the Christians against Mithraism; as Ruck states,

Subsequently, the dominating Christians attempted to eradicate the religion with all the fervor of persecution that themselves had recently suffered, desecrating the sanctuaries and even murdering Mithraic priests. In the Saarburg Mithraeum the skeleton of a man was found lying face downward with his wrists bound with an iron chain behind his back, probably a priest murdered and ritually cursed. His burial in the sanctuary was meant to desecrate it for all eternity.[60]

The fall of Mithraism in the Western Roman Empire, alongside the decline of the Sassanid Empire, marked the end of an era for this ancient deity. This paper concludes the series I started 9 months ago, examining the 2400 years of Mithraic worship from the Yamnaya of the Bronze Age to the end of the Classical Civilizations of Rome and Persia. The enduring legacy of Mithras across these diverse cultures from Rome to India highlights a continuous thread in the tapestry of Indo-European spiritual history, illustrating how an ancient deity can transcend time and geography, adapting to new contexts while retaining his core theological significance and overcoming history itself.

[1] Franz Cumont The Mystery of Mithra, 38

[2] Jason Reza Jorjani, Iranian Leviathan: A Monumental History of Mithra’s Abode, 179.

[3] Mithras, the Secret God By M. J. Vermaseren, 32

[4] Ibid

[5] D. Jason Cooper, Mithras: Mysteries and Initiation Rediscovered, 27.

[6] Jorjani, 185

[7] Pliny, Natural History, 3.6.

[8] Carl A. P Ruck, Mark A. Hofferman, Jose Celdran. Mushrooms, Myths & Mithras: The Drug Cult that Civilized Europe. 28

[9] Ruck. 28

[10] Cooper, 29-30

[11] Tacitus Histories 2.82

[12] Franz Cumont The Mystery of Mithra

[13] Cooper, 30

[14] Cumont 60-1

[15] Cumont, 61.

[16] Cumont 64

[17] Cooper, 30

[18] Cumont 64

[19] Cooper, 31

[20] Vermaseren, 34

[21] Vermaseren 35/Cooper 31

[22] Cassius Dio (Roman History, Book 77, Chapter 15)

[23] Vermaseren 27-8

[24] Carl A. P Ruck, Mark A. Hofferman, Jose Celdran. Mushrooms, Myths & Mithras: The Drug Cult that Civilized Europe , 31

[25] Cumont, 37

[26] Vermaseren, 35-6.

[27] Cumont 199

[28] Vermaseren, 188

[29] Vermaseren, 189/Cumont, 88-9

[30] Emperor Julian, Hymn to King Helios, Section 3

[31] Cumont, 73

[32] Vita Car., 12-13; Vict., Caes 38.4 f; Eutrop IX. 18; 20; Zonar XII. 30 f, p 611; Syncell., Chron., p 724 f; Oros. VII, 24.4.

[33] Spengler, Oswald. The Decline of the West: Perspectives of World History. Translated by Charles Francis Atkinson. 1. Vol. 1. 2 vols. London: Forgotten Books, 2018. Pg. 310-1

[34] Vermaseren 187-8/ Cumont 64-70

[35] Ibid

[36] Jorjani, 180

[37] Ruck, 31-2

[38] Ruck, 33

[39] Jorjani, 173

[40] MacMullen, Ramsay. Christianizing the Roman Empire (A.D. 100-400). Yale University Press, 1984.

[41] Lenski, Noel. The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine. Cambridge University Press, 2006.

[42] Michele R. The Making of a Christian Aristocracy: Social and Religious Change in the Western Roman Empire. Harvard University Press, 2002./ Stark, Rodney. The Rise of Christianity: A Sociologist Reconsiders History. Princeton University Press, 1996.

[43] Barnes, Timothy D. Constantine and Eusebius. Harvard University Press, 1981.

[44] Odahl, Charles M. Constantine and the Christian Empire. Routledge, 2004.

[45] Jorjani, 194-6

[46] Ibid

[47] Ibid

[48] Abbot Giuseppe Ricciotti Julain The Apostate, 41

[49] Ricciotti, 64

[50] Ruck 32

[51] Ibid

[52] Ibid, 191-2

[53] Jorjani 180

[54] Ruck, 32

[55] Cumont, 64

[56] Gibbon, Edward. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Edited by David Womersley. 1. Vol. 1. 6 vols. London, UK: Penguin Press, 1994.Pg 959-960

[57] Brown, Peter (1998). Pg.638-40

[58] Brown, Peter. Power and Persuasion in Late Antiquity: Towards a Christian Empire. University of Wisconsin Press (1992). Pg.107

[59] MacMullen, Ramsay. Christianizing the Roman Empire: (A.D. 100-400). New Haven, CNT: Yale University Press, 1984. Pg 90

[60] Ruck, 33

[61] Vermaseren, 189-90

[62] Ibid

This is the best description and analytical summary of Mithraism of Rome I have come across yet. Thank you for a profound exploration of the facets and details surrounding the way Mithraism became established in Rome, how it flourished and essentially ended. I deeply appreciate your work, it puts a lot of context to some of the more basic history I knew before.

This also fills in some areas of gaps in my own knowledge related to how this cult may have held influence at least in part for the establishment of Christianity.

We had a brief conversation on some of this topic in the 'chat.' It's probably easier to use the comment section.