Mithra's Mountain Abode: How the Kalash People Keep the Ancient Flame Alive

Analysis of the Religion, Ritual, and Cultural Reality of the Indo-Aryans of Northern Pakistan

During the height of the Great Game between the British and Russian Empires, as they vied for control over Central Asia, the British Raj sent explorers, surveyors, and intelligence officers into the mountainous Hindu Kush region. Their aim was strategic: to map the terrain, observe the Afghan Kingdom, and gauge the extent of Russian expansion. In these expeditions, British agents unexpectedly encountered reports of a mysterious, fair-skinned people living in remote valleys, speaking a strange Indo-Aryan language, and worshipping pagan gods. Victorian observers, influenced by romanticism and racial theories of the time, saw the Kalash as a living anachronism, seemingly untouched by Islam and modernity. Fascinated by their lighter skin, pre-Islamic religion, and ancient customs, colonial scholars speculated wildly. The most persistent myth was that the Kalash were descendants of Alexander the Great’s soldiers, left behind during his campaigns in the fourth century BCE. Though unfounded, this idea was reinforced in George Scott Robertson’s influential 1896 ethnography, The Kafirs of the Hindu-Kush, which depicted the Kalash as remnants of a Hellenistic era. Robertson noted similarities in dress, rituals, and social structure, appealing to a European audience eager to find reflections of themselves in the "exotic" East. Although modern scholarship mostly dismisses these claims as orientalist fantasy, the fascination offered some insight. The Kalash are not a Macedonian colony, but may represent an older cultural link to the Proto-Indo-European world of the Bronze Age, not Alexander. Their language, customs, and cosmology show Indo-Aryan patterns linked to migrations and traditions from the steppe cultures into South Asia. While scholarly focus is on great civilizations like the Indo-Aryans, the Iranian empires, the Greeks, and the Romans, smaller groups like the Kalash often go unnoticed. These groups weren't fully assimilated into monotheistic or centralized states and preserved echoes of an older Indo-European world. The Kalash of northern Pakistan are particularly intriguing: a secluded Indo-Aryan population with a polytheistic religion, sacred festivals, and an archaic language that contrast starkly with their Islamic neighbors. While they are not a fossilized relic, the Kalash may be seen as a living cultural time capsule, retaining social and religious structures that predate Islam, Buddhism, and even the classical Hindu tradition. Their endurance offers a rare window into the spiritual and cultural landscape of early Indo-Iranian peoples, and challenges modern assumptions about cultural survival and transformation. This paper seeks to examine the Kalash not as a curiosity frozen in time, but as a dynamic community shaped by isolation, resistance, and the long shadow of Indo-European antiquity.

Historical and Linguistic Origins

The Kalash people inhabit the remote valleys of Bumburet, Rumbur, and Birir in the Chitral District of northern Pakistan. Despite their relatively small population, they have garnered considerable scholarly interest due to their links with early Indo-European peoples. The Indo-European language family is widely theorized to have originated in the Pontic-Caspian steppe, based on linguistic reconstruction and archaeological findings, such as those associated with the Yamnaya culture.[1] From this hypothesized Urheimat or homeland, Indo-European languages dispersed across Europe and large portions of Asia in successive waves of migration. One of the branches is Indo-Iranian, which would split into Iranian moving southeastward into the Iranian plateau and Indo-Aryan subgroups into the Indian subcontinent, where they profoundly influenced the linguistic and cultural landscape.

The Kalash language, or Kalasha-mun, is classified within the Dardic languages, traditionally considered a subgroup of Indo-Aryan. However, the categorization of Dardic as a coherent linguistic unit remains debated, as scholars such as Morgenstierne argue that "Dardic" is more of a geographic designation than a linguistic one, used to group together languages spoken in the mountainous regions of northern Pakistan, eastern Afghanistan, and parts of India.[2] This ambiguity complicates efforts to place Kalasha definitively within the Indo-Aryan lineage, though its Indo-European roots are not in dispute. What sets Kalasha apart is its remarkable retention of archaic linguistic features. Unlike most modern Indo-Aryan languages, Kalasha preserves consonant clusters and grammatical case inflections that are more typically found in ancient Indo-Aryan languages like Vedic Sanskrit. For example, Kalasha uses a full set of grammatical cases for nouns, including nominative, accusative, genitive, and dative forms. Bashir notes that "Kalasha exhibits conservative features within its nominal morphology, preserving distinctions that have been lost in most modern Indo-Aryan languages."[3] The Kalasha language is striking in its lexical conservatism, preserving ancient Indo-Aryan roots and vocabulary that have long disappeared from neighboring tongues. This linguistic archaism has led some to call it a “living fossil” of early Indo-Aryan speech, a rare echo of the linguistic world that once stretched from the steppes to the subcontinent. Far from being stagnant, however, Kalasha has evolved in its own isolated rhythm, retaining ancestral elements while subtly adapting to its mountainous surroundings and occasional external contact. It offers not only a window into the past but also a testament to the resilience of linguistic identity across millennia. Furthermore, the complexity of Kalasha-mun is that it’s not mutually intelligible with surrounding languages such as Khowar, despite centuries of geographic proximity. According to Heegård and Mørch, Kalasha vocabulary and phonology preserve aspects that seem more closely aligned with early Vedic Sanskrit than with most Indo-Aryan vernaculars.[4] For instance, the Kalasha word for sun, suri, is phonetically and semantically similar to the Sanskrit sūrya. Additionally, Kalasha’s verbal system includes tenses and aspects that align with Indo-Aryan structures but show significant innovation and independent development. The continued use of ergative constructions and split-ergativity reflects both ancient syntactic features and adaptive changes over time. As Degener writes, "Kalasha verbal syntax presents a complex interplay of archaism and innovation, illustrating a dynamic evolution within an isolated environment."[5] Geographic seclusion has played a crucial role in the preservation of Kalasha-mun and associated cultural practices. The rugged terrain of the Hindu Kush range limited interaction with larger Indo-Aryan populations and helped the Kalash maintain linguistic and cultural distinctions. The Kalash represent a vibrant, living tradition shaped by linguistic conservatism, creative adaptation, and centuries of relative isolation. Their continued existence provides a window into the diversity and complexity of the Indo-Aryan world. However, their language is currently endangered, with increasing pressure from dominant regional languages such as Khowar, Urdu, and Pashto. Organizations like the Forum for Language Initiatives and UNESCO have recognized Kalasha-mun as a vulnerable language. Documenting and revitalizing this linguistic heritage are not only essential for the Kalash community but also for scholars seeking to understand the historical evolution of Indo-European languages in Central Asia.

Religion and Culture of the Kalash People

Although the Kalash do not identify as “Indo-Aryan” or “Indo-European,” some of their oral traditions speak of origins in a “distant land to the west.” These stories are vague and mythic, but they may be a form of mytho-genetic echo, distorted remnants of the ancient Indo-European migrations from the Pontic-Caspian steppes. Through rituals, poetry, and cosmological tales, these ancestral memories function not as literal history but as a spiritual remembrance of a homeland whose exact shape has long disappeared. In this view, Kalash myths do not conflict with archaeology; instead, they reflect cultural continuities too subtle to be uncovered: the retention of Bronze Age cosmologies, seasonal rites, and moral dualisms long after the world that created them vanished. These stories serve more as a mythic compass than a geographic map, pointing to a cultural time rather than a physical location, marking a primordial Yamnaya identity. Thus, the Kalash are linked to the broader Indo-Aryan peoples of the premodern era through shared faith and cultural practices, within the framework of Indo-European history. They uphold a highly unique and symbolically rich belief system that combines animism, polytheism, ancestor veneration, and Indo-Aryan sacred cosmology. Unlike the majority Muslim population of Pakistan, the Kalash continue to practice a pre-Islamic Indo-Aryan religion rooted in nature reverence, ritual purity, and seasonal festivals. Their traditions provide a rare glimpse into ancient Indo-Aryan or Indo-European spiritual practices, filtered through centuries of local adaptation. The Kalash religion is polytheistic, with a diverse pantheon overseeing life, nature, and cosmic order. This reflects a worldview rooted in Indo-European tradition, emphasizing the sacred bond between natural forces, morality, and the cosmos.

At the apex of the Kalash pantheon stands Dezau (also known as Khodai), the supreme creator deity and cosmic architect. Dezau is conceptualized as a transcendent yet immanent force, responsible for the genesis of the universe and the establishment of a moral order that sustains life and community. This idea aligns with other ancient Indo-European deities like Ahura Mazda, Brahman, and the Platonic One, all representing a universal, foundational essence rather than a personal god. This suggests a shared cultural origin, possibly from the Yamnaya, who may have had an early concept of a singular cosmic first principle as a universal, divine essence. Unlike the more frequently venerated gods of the pantheon, Dezau is not the focus of regular ritualistic practice but is invoked primarily during moments of significant communal distress or existential threat, such as droughts, earthquakes, or epidemics. This pattern of invocation highlights his role as an overarching divine overseer, a guardian of cosmic balance whose presence ensures the maintenance of order (often understood as harmony between humans, nature, and the spirit world). This ritual economy echoes the function of the Indo-Iranian Dyaus Pitar or the Vedic Dyáuṣ Pitṛ́, the sky father figure who embodies the overarching heavens and moral authority. Other prominent deities in the Kalash pantheon exhibit traits that align with Indo-European mythological archetypes. For example, Balumain, a god associated with warfare, fertility, and the winter solstice festival Chaumos, parallels the figure of the warrior-culture hero archetype seen in Indo-European traditions similar to the Vedic god Indra, the Norse Týr, or the Greek Ares. This shared similarity of gods that Balumain exhibits thematic parallels with the ancient Indo-Iranian deity Mithra (or Mitra in the Vedic tradition), who was associated with solar divinity, contracts, protection, and truth. While there is no direct textual continuity, Balumain’s role as a mediator between cosmic and social orders, his seasonal appearance, and his solar festival associations resemble Mithraic motifs.[6]

Balumain’s connection to seasonal cycles also reflects the ancient Indo-European preoccupation with the rhythms of nature and the sacralization of agricultural and cosmic time. A more personally involved deity is Balumain, regarded as a culture hero and god associated with warfare, fertility, social harmony, and the sacred festival of Chaumos. Balumain is said to descend into the valleys during Chaumos to bless the people, and his mythic journey symbolizes renewal, prosperity, and the cyclical turning of the seasons. He is both a mythical ancestor and a living presence, with rituals dedicated to him often including dance, fire, and animal sacrifice. Additionally, the Kalash recognize Jestak, a goddess of domesticity and fertility, who is venerated particularly by women and is associated with protection, fertility, and domestic harmony. Every Kalash household has a Jestak shrine or Jestak Han, often located near the kitchen or in a specially demarcated sacred space, where offerings are made to maintain her favor. This reflects the widespread Indo-European reverence for goddesses who govern the household and reproductive cycles, akin to the Roman Vesta or the Greek Hestia. Mountain spirits, such as Sajigor, another key deity, preside over boundaries, both physical and moral, as he embodies the sacred geography so central to the Kalash cosmology, much like the reverence for natural features found in Celtic, Greek, and Slavic polytheisms, where divine or semi-divine entities inhabit mountains, rivers, and groves. Sajigor is invoked in rituals concerning the village, agriculture, and communal law, underscoring his role as a guardian of both land and social norms. Sajigor, too, may echo aspects of Mithra’s ancient Indo-Iranian function as a protector of oaths, guardian of order, and enforcer of moral codes, although filtered through a distinctly local and non-textualized lens. This divine multiplicity is embedded within a broader cosmology emphasizing purity, balance, and cyclical renewal concepts deeply resonant with Indo-European religious ethics. The Kalash maintain strict ritual boundaries between purity and impurity, a division reminiscent of the ṛta (cosmic order) and dharma (moral law) that governed Indo-Aryan religious thought. These deities, beyond abstract metaphysical constructs, are intimately embedded in the landscape and everyday life of the Kalash. As Parkes explains, Kalash deities are “manifest in the world through ritual, through human morality, and through the landscapes they inhabit.”[7] Their presence is visible in sacred places, such as mountain peaks, springs, and ancient groves, which are considered to be dwelling places of spirits and divinities. These sites must be approached with ritual purity, and violations of these sacred spaces are believed to invite misfortune or divine retribution. This sacralization of the environment, a trait found in many other Indo-European religions, underscores a deeply rooted ecological ethos in Kalash cosmology. Nature is not merely a backdrop for human activity but an animate, moral universe suffused with divine presence. The Kalash landscape is a "ritualized ecology," where interactions with the environment are governed by respect, reciprocity, and a recognition of spiritual immanence. This perspective has practical implications: hunting, farming, and gathering are all subject to ritual protocols that maintain ecological balance and social cohesion.

Kalash rituals are heavily influenced by the notion of purity (onzar) and impurity (pragata), which guide interactions with deities, animals, food, and even other humans. There is a marked division between the sacred and the profane, particularly in relation to gender and spatial organization. Women, for example, are temporarily sequestered during menstruation and childbirth in special houses called bashali. Ritual specialists, known as shamans or dehar, play a central role in mediating between the human and spiritual realms, recalling the Vedic soma rituals or the sacred rites of Zoroastrianism aimed at maintaining cosmic harmony. These individuals perform sacrifices, often involving goats or bulls to appease the gods, ensure fertility, or protect the community from misfortune. Public rituals are communal affairs, reinforcing social cohesion and collective memory as “To be Kalash is to participate in ritual; identity is enacted through seasonal celebrations and sacrificial acts.”[8] Kalash religious festivals are complex, multi-day events that blend music, dance, storytelling, and sacrificial offerings. They are keyed to seasonal cycles and agricultural rhythms, marking solstices, harvests, and transitions between social and cosmological phases. The most important Kalash festival is Chaumos, held in December, which marks both the New Year and a ritual reenactment of the Kalash origin myth. Rich in symbolism, Chaumos bears striking parallels to other Indo-European winter solstice traditions. Like the Persian Yalda Night and the Roman Saturnalia, Chaumos celebrates the rebirth of the sun and the renewal of cosmic order. Saturnalia, dedicated to Mithras, and Yalda, celebrating the longest night of the year, both center on themes of light returning after darkness, a motif echoed in Chaumos, when the deity Balumain is believed to descend into the valleys. The Kalash respond with ecstatic dances, ritual fire ceremonies, and competitive games, recalling the festive inversion, revelry, and spiritual renewal found in other ancient solstice rites across the Indo-European world. These shared elements suggest that Chaumos may preserve deep-rooted Indo-European ritual structures, adapted to the Kalash's unique mountainous context. Other major festivals include Joshi (spring fertility festival), Uchao (autumn harvest), and Pul (commemorating the dead). Each festival encapsulates different aspects of Kalash cosmology and social organization, highlighting values of hospitality, generosity, and cosmic balance. These festivals also serve as moments of intergenerational transmission, where elders instruct youth in the meanings and procedures of sacred rites.

The Kalash people's fascinating religious traditionalism that anchors itself in the pure archetypes or Platonic forms of Indo-European spirituality has been durable in the reality of their situation of centuries of contact with neighboring Muslim populations and increasing pressure to convert. The Kalash have retained their religious practices with remarkable tenacity. At the same time, some have adopted Islamic customs for practical reasons, but a strong sense of cultural identity continues to anchor their religious distinctiveness. The Pakistani state recognizes the Kalash as a distinct religious and ethnic minority, and various NGOs have worked to support cultural preservation. At the same time, syncretism is visible in subtle ways. Some Kalash now refer to Dezau as Allah in public discourse, while maintaining traditional rituals in private. This pragmatic accommodation is not necessarily a sign of religious dilution but rather a strategy of cultural resilience, as the “Kalash cosmology is not a static relic but a living system capable of incorporating new elements while preserving core values.”[9] In sum, the religion of the Kalash is a richly layered and deeply contextualized spiritual tradition that resists simplistic categorization. As perhaps the only extant community preserving an unbroken thread of Indo-Aryan religious practice from the Bronze Age into the modern era, the Kalash offer a rare and invaluable window into the ancient spiritual worldview of early Indo-Europeans. For those approaching from a Traditionalist or comparative religious perspective, Kalash cosmology provides living insight into the ethical, ecological, and ritual sensibilities that may have once shaped the Yamnaya and Andronovo cultural spheres. Any serious attempt to reconstruct Proto-Indo-European religion, whether for academic scholarship or spiritual revival, must consider Kalash mythology and ritual life as a vital reference point, alongside Zoroastrianism, Vedic Hinduism, Platonism, and the European pagan traditions.

Modern Realities of the Kalash People

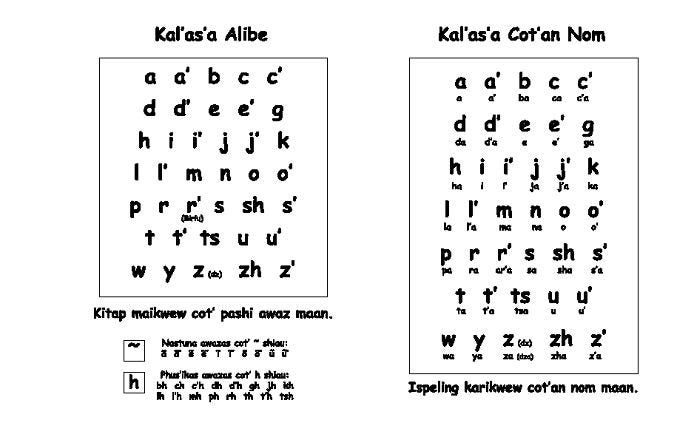

The Kalash people today exist at a complex intersection of tradition and modernity, navigating pressures from globalization, religious conservatism, and state politics. While their unique cultural and religious identity has garnered international attention and occasional support, the Kalash face a number of existential threats from economic marginalization and cultural assimilation to environmental degradation and religious conversion. Understanding their modern realities requires an integrative approach that examines socio-political dynamics, education, tourism, and internal community adaptations. The Kalash are a small ethnic minority, numbering between 3,000 and 4,000 people. As a recognized religious minority in Pakistan, they are granted limited constitutional protections under Article 36 of the Pakistani Constitution, which requires safeguarding minority rights. However, these protections are often enforced inconsistently. According to the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, Kalash communities have reported incidents of land encroachment, limited access to public services, and threats of forced conversion.[10] Politically, the Kalash lack significant representation. Although NGOs and international observers sometimes voice their concerns, the absence of strong advocacy within the government leaves them vulnerable to changing political priorities. As “the Kalash experience inclusion largely as tokenism, rather than meaningful representation.”[11] One of the biggest challenges for the Kalash is the ongoing pressure to convert to Islam. Conservative religious groups have been active in the region, offering financial aid, educational opportunities, and social acceptance in exchange for conversion. While these efforts are often presented as charity and outreach, local leaders describe them as coercive. Conversion often isn’t just a personal religious choice but a complex negotiation involving poverty, access to opportunities, and intercommunal tensions. One Kalash elder explained, “They say we can have roads, schools, medicine—if we become like them.”[12] These dynamics create divisions, as converts may enjoy privileges while others remain economically isolated. Despite this, many Kalash continue to resist conversion, relying on a strong sense of cultural identity and community bonds. Public celebrations, rituals, and oral traditions are key ways they preserve their religious life amid external pressures. Education is another double-edged sword. On one hand, literacy and schooling are vital for empowering Kalash youth and increasing their political agency. On the other hand, formal education is often conducted in Urdu or English, with little accommodation for the Kalash language. This language displacement threatens the passing down of oral traditions, songs, myths, and rituals across generations. Efforts to preserve the Kalasha language have gained momentum recently. Local projects, supported by linguists and anthropologists, have created textbooks, dictionaries, and language apps for Kalasha. These efforts aim to combine cultural preservation with modern tools: “The key to Kalash survival may lie in hybrid strategies—embracing education while maintaining the oral lifeblood of their tradition.”[13]

Conclusion

The Kalash people are a unique and often overlooked thread in the rich tapestry of Indo-European identity. They embody a primordial tradition, rooted in ancient cultural and religious practices that have endured despite the leveling forces of modernity. Their story is one of remarkable resilience, maintaining cultural coherence against pressures toward uniformity, abstraction, and dissolution. The Kalash stand as a living testament to the endurance of Indo-European tradition, preserved in a remote corner of the Hindu Kush. Their polytheistic cosmology, ritual life, and social structures offer rare anthropological insight into early Indo-European societies, echoing the spiritual architecture of cultures long thought lost. Their language, festivals, and sacred geographies form a palimpsest of memory, expressing continuity with a broader Eurasian civilizational arc, one that still breathes, even as the modern world forgets how to listen. Yet this endurance is precarious, dependent not only on their steadfastness but on a broader willingness to recognize the value of rooted tradition in an age that privileges the ephemeral. The Kalash are not merely a cultural anomaly; they are a symbol of how depth can survive surface, and how vertical forms of order might persist within the horizontal flattening of modernity. Studying the Kalash is not simply to preserve a cultural curiosity. It is to witness the persistence of form in the age of flux, a meditation on how identity, myth, and sacred order may yet endure, riding the currents of a world unmoored. Though their world is small, its implications are vast: a reminder that tradition is not the enemy of change, but the anchor that makes meaningful transformation possible.

[1] Anthony, David W. The Horse, the Wheel, and Language How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton University Press, 2010.

[2] Morgenstierne, Georg. Kalasha Language Texts and Translations Vocabulary and Grammar. Ishi Press, 19 Feb. 2016.

[3] Bashir, Elena. The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge, 2003.

[4] Arsenault, Paul. “Two Types of Retroflex Harmony in Kalasha: Implications for Phonological Typology.” Studies in Languages of Northern Pakistan and Surrounding Regions: in Memory of Carla Radloff, 2021.

[5] Degener, Almuth. 1998. Die Sprache von Nisheygram im afghanischen Hindukusch. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

[6] Boyce, Mary. Zoroastrians : Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. London ; New York, Routledge, 2001.

[7] Parkes 1999, 1; World Minorities Report 4

[8] Jones, 2010.

[9] Maggi, Wynne. Our Women Are Free. University of Michigan Press, 2001.

[10] HRCP, 2021

[11] Ali, Muhammad Kashif (2011), “Kalash Culture”, Ancient History Encyclopedia,

https://www.ancient.eu/Kalasha/

[12] Wynne, 2001.

[13] Ibid

Like many of your posts, this one is a treasure. What you point out about the Kalash is profound, both in the sense of historic essence and for the importance of their preservation.

You wrote: "The Kalash are not merely a cultural anomaly; they are a symbol of how depth can survive surface, and how vertical forms of order might persist within the horizontal flattening of modernity." -- Very powerfully stated.

In the process of writing part 4 of the series I was working on, regarding Yahweh; I became aware of just how impactful the force of trade and commerce was in the ancient Mediterranean. It seems Religion was one way to commoditize and enforce Regional Trade Zones. This appears to be something that started with the Phoenicians, but I think it started much earlier.

When you bring up the topic of pressure to convert being exerted on the Kalash People, you point out the way they are being pressured economically; this rings true for the ancient world. The way the Habiru people having to conduct business in some ancient cities could have been constrained by their cultic views or practices. Even some seafaring people like the Aḫḫiyawa or Achaeans were constrained from certain areas. (The Amarna Letters are helpful here)

Your quote: "One Kalash elder explained, “They say we can have roads, schools, medicine—if we become like them.”[12] These dynamics create divisions, as converts may enjoy privileges while others remain economically isolated. Despite this, many Kalash continue to resist conversion."" -- This gives me a real sense of hope, that their way of viewing world both natural and spiritual is being defended. The Kalash are a cultural treasure in themselves because they point a way to touch our own ancient roots.