Mithra, The Hidden Sun of The Aryans Part 3: The Arrival of Mithra into the Hellenistic World

The Phenomenon of the Hellenic Perseus cult and the Mithridatic Wars Against Rome

The Hellenic Mithra story is a compelling testament to the intricate tapestry of religious syncretism that characterized the ancient world. Rooted in the adoration of Mithra, a deity originating in Persian mythology, this cult underwent a fascinating journey of adaptation and dissemination in the Hellenistic world, ultimately flourishing within the cultural milieu of Rome. Through a meticulous examination of historical sources, archaeological findings, and comparative religious studies, this paper endeavors to unravel the complexities of this transference, shedding light on this forgotten stretch of history on a forgotten God and how the worship of Mithra traversed geographical and cultural boundaries to become an integral facet of the Roman religious landscape. In the Parthian Empire, the center of Mithraic worship during the Hellenistic era, the Arsacid dynasty believed that the Iranian race was a decedent of the Greek hero Perseus via his son Perses, the founder of the Persians. The figure of Perseus was seen as the first Magi and in a Mithraic-Promethean sense as he brought the celestial fire to earth for the Aryans.[1] This Irano-Hellenic synthesis was characteristic of the Parthian Empire, as they did not limit themselves to passive adoption of the Perseus myth; rather, the Parthians embraced this mythological origin into the Parthian identity itself. To the Parthians, Perseus was seen as Mithra, thereby making the Parthians descendants of Mithra himself, as Jason Reza Jorjani in his book Iranian Leviathan: A Monumental History of Mithra’s Abode states

In the wake of the Hellenization of Persia during the Seleucid period, the Parthians really embraced this idea. Mithradates II had himself depicted as Perseus on some of his coinage, which also featured the harpe sword as well as the crescent and star. The harpe sword was given to Perseus by Hermes. The harpe together with the crescent moon and star is the symbol of the fifth grade of initiation in Mithraism, the grade of Perses or “the Persian,” and the symbol of the seventh grade of “the Father” — which refers to Perseus or Mithra himself — is a curved knife next to a Phrygian cap with a staff and bowl Mithradates I believed that the Parthian dynasty were descended from Perseus, via his son Perses. Given that he also traced his lineage to the Achaemenids, via Darius III, this means that Mehrdâd wanted to see himself and his heirs as Persians, whether or not they actually were as a matter of ethnographic fact. The Gorgon and Pegasus are also depicted on his coins, as well as those of Mithradates III and IV. Mithra is none other than Perseus himself and the bull-sacrifice or tauroctony imagery at the heart of the Mithraic mystery is an astrologically encoded version of his heroic Gorgon-slaying. Mithras is simply the Greek pronunciation of the name “Mithra” (or Mitra). The original Iranian version of the god’s name will be used here. Mithra is a youth wearing a tunic and a Phrygian cap.[2]

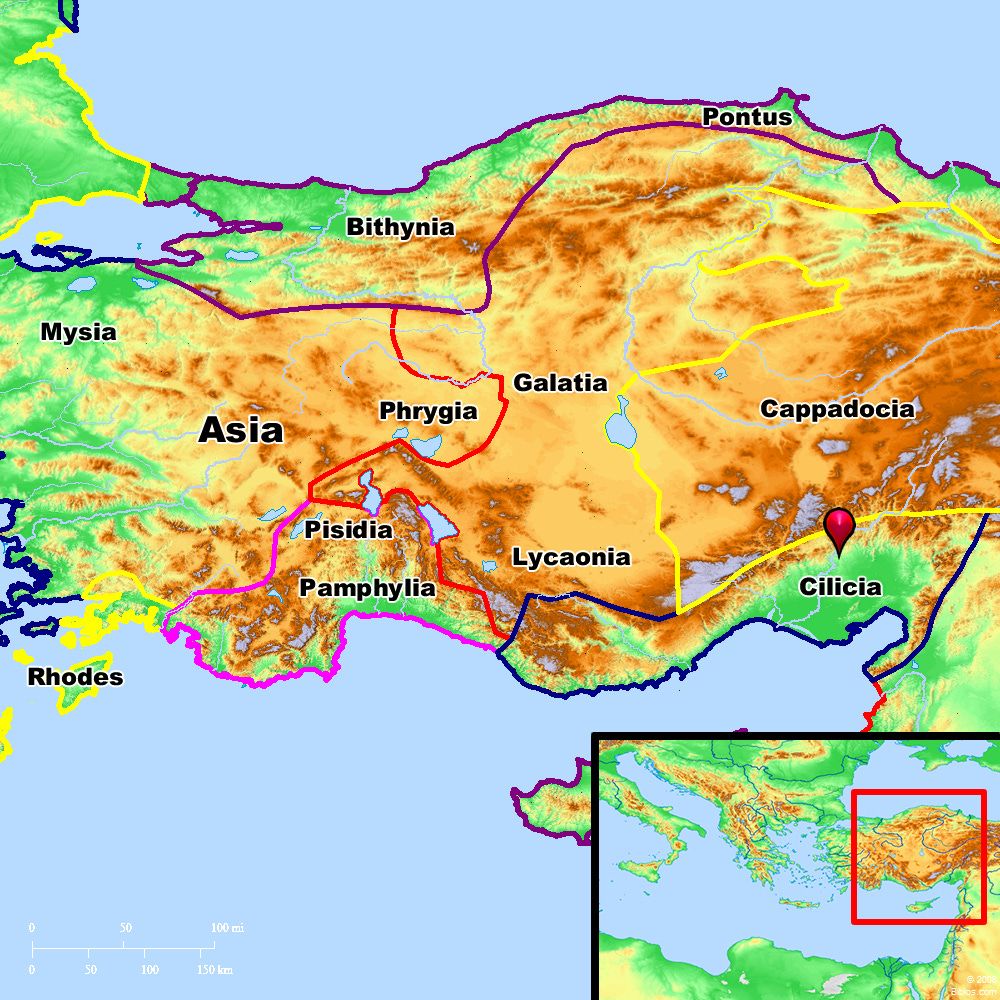

As the Mithraic Parthian Empire expanded westward at the expense of the Seleucid Empire, so did the Mithraic faith take root, signifying the Parthian Imperium, which brought Mithra into contact with the Hellenistic world.[3] This expansion of Parthian influence would revitalize the preexisting Mithraic faith established by Cyrus the Great in Anatolia, which coincided with the chaos of Post-Alexandrian Anatolia where Persian, Celtic, native Aryan Anatolian dynasties, and Hellenic Kingdoms struggling for control of Asia Minor. This environment of strife would create the conditions for the growth of the embryonic European Mithraic cult.[4] According to the founder of Mithraic studies, the Belgian scholar Franz Cumont argues that the Mithraic cult was adopted by the Phrygians, the Anatolian, and Hellenic populations from the Persians, then would be responsible for passing off Mithra to the Romans. Add to this idea, Iranian historian Parvaneh Pourshariati, in her book Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran, argues that “Mihr worship was one of the most popular forms of religiosity in pre-Christian Arsacid Armenia, so much so that some scholars claim that the region was the provenance of Roman Mithraism.”1 Hence, Armenia was the transfer point between the Parthians and the Anatolians; this would explain Cumont’s conclusion of the Parthian origin of Anatolian Mithraism, reinforcing a preexisting Iranic religious mentalité of the European Mithra cult. The evidence from Anatolia during the Achaemenid era shows that Asia Minor was heavily Persianized, and this Irani-Anatolian culture would survive the Alexandrian conquest of the region, [5] as Cumont states,

The sacrifices of the pyrethes which Strabo observed in Cappadocia recall all the peculiarities of the Avestan liturgy. The same prayers were recited before the altar of the fire while the priest held the sacred fasces (baregman) ; the same offerings were made of milk, oil and honey ; and the same precautions were taken to prevent the priest’s breath from polluting the divine flame. Their gods were practically those of orthodox Mazdaism. They worshiped Ahura Mazda, who had to them remained a divinity of the sky as Zeus and Jupiter had been originally. Below him they venerated deified abstractions (such as Vohumano, “good mind,” and Ameretat, “immortality”) from which the religion of Zoroaster made its Amshaspends, the archangels surrounding the Most High. Finally they sacrificed to the spirits of nature, the Yazatas: for instance, Anahita or Anaites the goddess of the waters—that made fertile the fields; Atar, the personification of fire; and especially Mithra, the pure genius of light. Thus the basis of the religion of the magi of Asia Minor was Mazdaism, somewhat changed from that of the Avesta, and in certain respects holding closer to the primitive nature worship of the Aryans, but nevertheless a clearly characterized and distinctive Mazdaism, which was to remain the most solid foundation for the greatness of the mysteries of Mithra in the Occident.[6]

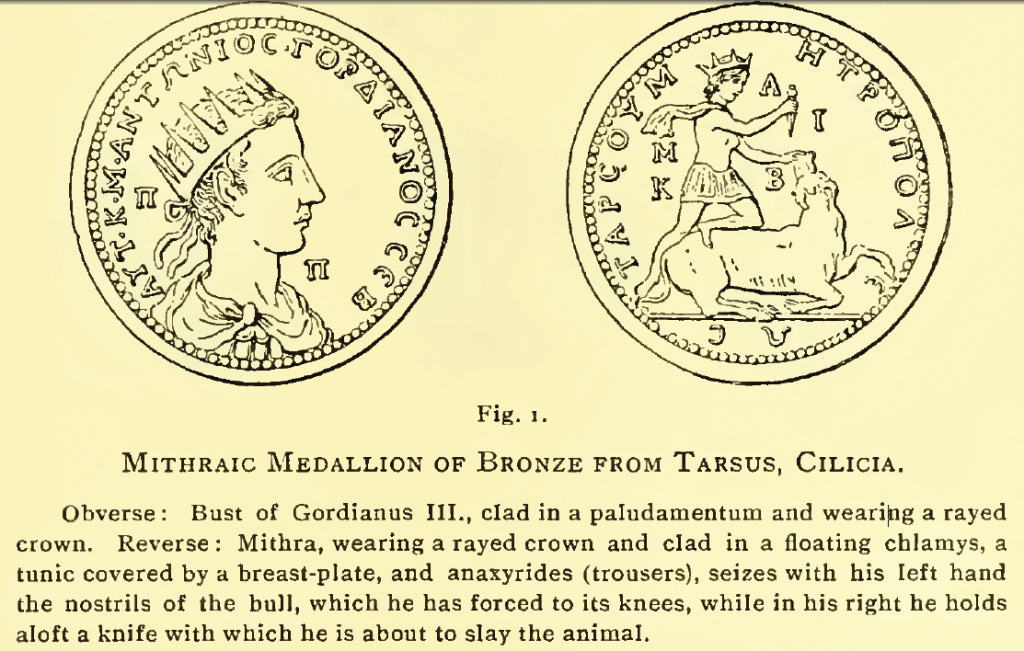

This environment of a more primitive Aryan-Iranian mentalité of faith unhindered by the Zoroastrian orthodoxy in the Achaemenid court allowed the Mithraic cult to dominate Anatolia and Armenia. Mithra became a key fixture of religious life, but this was nothing new as it was a revival or, in a sense, maintaining the ancient Hittite and Mitanni worship of Mitra native to the Aryan peoples of the Anatolian peninsula in the Bronze Age. Mithra’s restoration of his primordial Anatolian preeminence brings us to the region of Cilicia, where Mithra’s influence is historically pronounced, hinting that he was never forgotten. The area of Cilicia is situated in the Taurus mountains of modern southern Turkey, with a rich history of the flow of trade and armies, making the region a crossroads of Empire between the west and near east. The largest population center of the area, Tarsus, has had an archaeological presence since the Hittite Empire of the second millennium B.C. From there, Tarsus passed into the hands of various rulers, including the Assyrian and Persian Empires, Alexander the Great, and the Seleucids, who, under their stewardship, saw the city take on the characteristics of a typical Hellenic Polis.[7] Hellenistic Tarsus seems a significant expansionary vector for the Mithraic religion from Persia to Anatolia, to finally, the Western Aryans of Europe.

The city of Tarsus served as a perfect transfer point because of its geographic position between the Near East and Anatolia. However, geography aside, the defining factor in the Hellenization of Mithras resulted from the actions of philosophers united in their shared belief in astronomy and astrology that would define the occult doctrines of Mithra. These were the Stoic philosophers of Tarsus, who would become the first act of a causal chain that spread Mithra to the West. By the Hellenistic era, Tarsus had become an intellectual center of Greek civilization with a school of Stoic philosophy established, in the same vain as the Platonic Academy and Aristotle’s Lyceum in Athens or the Mouseion of Alexandria as Strabo relates in his work The Geography,

The people of Tarsus have devoted themselves so eagerly, not only to philosophy, but also to the whole round of education in general, that they have surpassed Athens, Alexandria. Or any other place that can be named where there have been schools and lectures by philosophers. But it is so different from other cities that there the philosophers. Put it is so different from other cities that there the men who are fond of learning are all natives, and foreigners are not inclined to sojourn there; neither do these natives stay there, they complete their education abroad: and when they have completed it they are pleased to live abroad and but few go back home. … Further, the city of Tarsus has all kinds of schools of rhetoric: and in general, it not only has a flourishing population but also is most powerful, thus keeping up the reputation of the mother-city.[8]

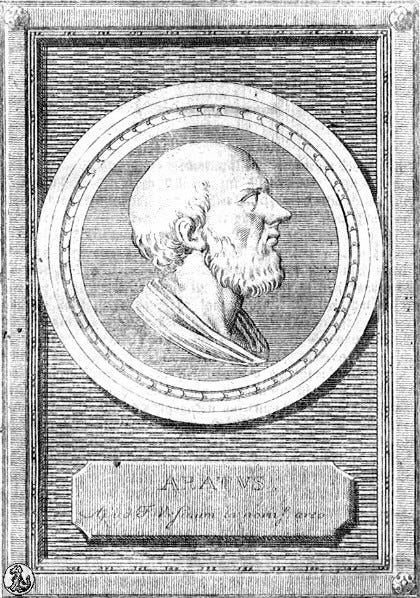

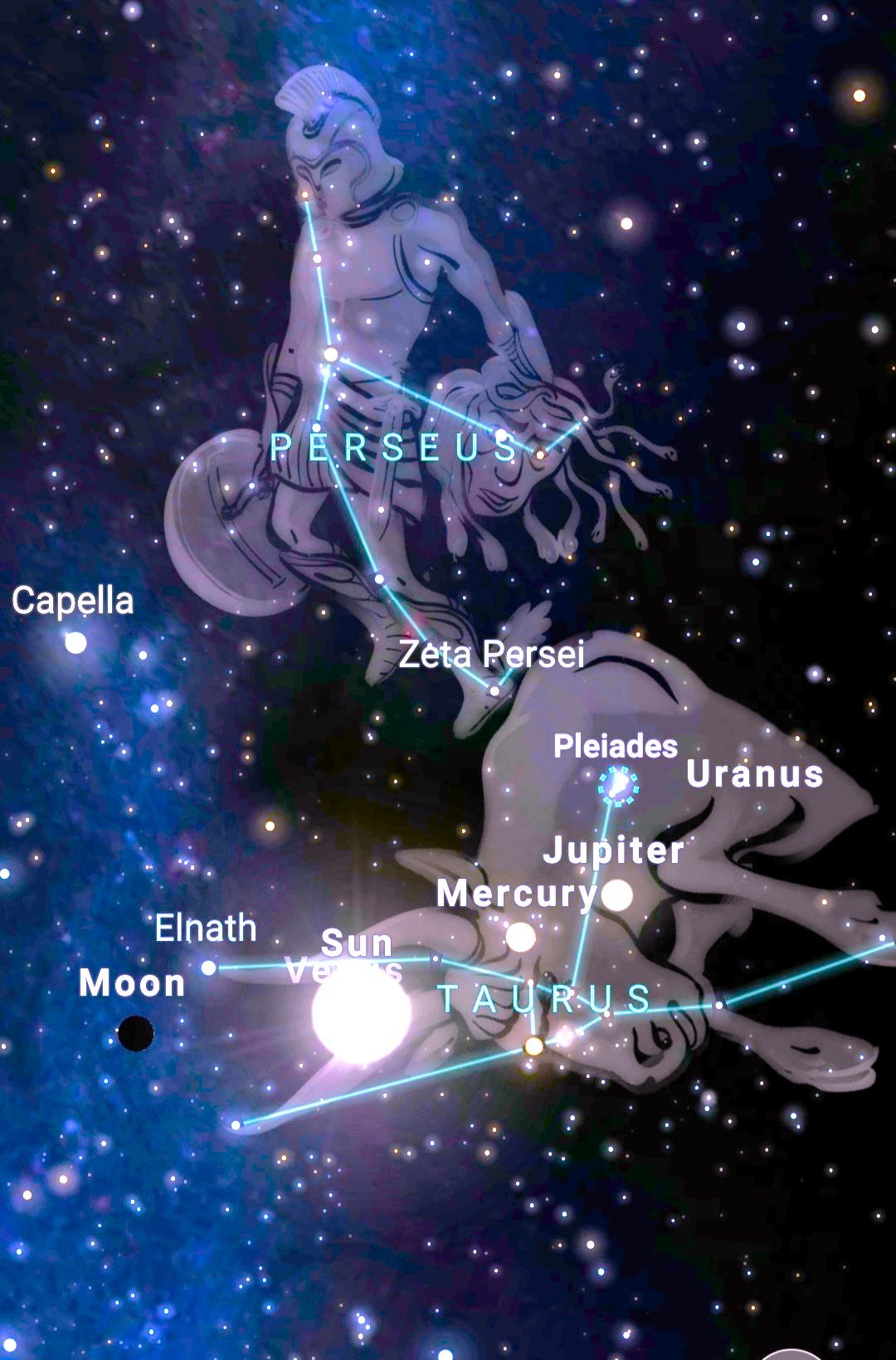

These intellectuals in Tarsus had developed a new religious schema influenced by Stoic ideas shaped by the growing popularity of astrology from “Chaldea”[9] but as well as scientific innovation in the field of astronomy such as astronomical cycles like Hipparchus' discovery of the precession of the equinoxes. This combination led the Stoic philosophers, starting with Aratos of Soli (315-240 B.C.), who authored the astronomical poem the Phaenomena,[10] thus the Stoics began to propose a new astrotheology around the existence of a powerful divinity responsible for this astronomical phenomenon which was in line with Stoic and Platonic ideas of a cosmological first cause for all existence. This Stoic belief would merge with the local Hittite-Luwian war god of Tarsus, known as Šanta or Šanada,[11] that evolved into the Hellenic hero-god, Perseus, who is also a constellation.[12]

Thus, it was this astrological and astronomical speculation that Franz Cumont, in his work The Oriental Religions in Roman Paganism, argues that Mithra did not come to the Greeks cleanly via Persia but partially through the middle man of the Semitic culture as;

Recent discoveries of bilingual inscriptions have succeeded in establishing the fact that the language used, or at least written, by the Persian colonies of Asia Minor was not their ancient Aryan idiom, but Aramaic, which was a Semitic dialect. Under the Achemenides this was the diplomatic and commercial language of all countries west of the Tigris. In Cappadocia and Armenia it remained the literary and probably also the liturgical language until it was slowly supplanted by Greek during the Hellenistic period… The divinities of the two religions became identified, their legends connected, and the Semitic astrology, the result of long continued scientific observations, superimposed itself on the naturalistic myths of the Persians. Ahura Mazda was assimilated to Bel, Anahita to Ishtar, and Mithra to Shamash, the solar god. For that reason Mithra was commonly called Sol invictus in the Roman mysteries, and an abstruse and a complicated astronomic symbolism was always part of the teachings revealed to candidates for initiation and manifested itself also in the artistic embellishments of the temple.[13]

Therefore, the interest in Babylonian astrology and Persian astronomy by the Stoics combined with the local Hittite/Luwian tradition of Šanta/Apaliunus/Mithra may be the causal link of how Mithra became reintroduced to the Aryan peoples of Anatolia via a syncretic astral religion. However, this is not to say that the Mithraic Cult is a Semitic religion. Instead, Semitic ideas may have been the vehicle that reintroduced these ideas into the Hellenic world. The Mithraic religion was Aryan in conception because of the compatibility of Hellenic and Persian beliefs in an Indo-European sense, which facilitated a natural syncretism, as Cumont continues,

The Greeks later translated the names of the Persian divinities into their language and imposed certain forms of their mysteries on the Mazdean cult. Hellenic art lent to the Yazatas that idealized form in which it liked to represent the immortals, and philosophy, especially that of the Stoics, endeavored to discover its own physical and metaphysical theories in the traditions of the magi[14]

Hence, it makes sense that the Stoic philosophers of Tarsus linked this new divinity of Perseus/Mithra to the symbol of a hero slaying a bull because of the astronomical discoveries of Hipparchus, which indicated that the spring equinox had moved from the constellation Taurus (the Bull) and the constellation Perseus, positioned above Taurus. This created the image of Perseus slaying the bull, signifying his immense power to shift the entire cosmos and end the Age of the Bull. This symbolism was strengthened by the city of Tarsus' emblem, which depicted a bull-slaying by a hero in the same manner as Mithra.[15] The central image of the bull-slaying deity solidified; other constellations along the celestial equator during the Taurus equinox were incorporated to demonstrate the god's control over the entire celestial equator.

Thus, the intellectual milieu of Tarsus and the Hellenistic world seems to be perfectly primed for the ideal conditions for the Mithra cult to take root in the Hellenistic world. The cutting-edge philosophical and astronomical trends of the late Hellenistic intellectual culture and Indo-European syncretic similarities could justify Mithra. Historical evidence shows the growth of Mithraism in this era, as the Mithraic scholar David Ulansey pinpoints the origin of the Hellenic Mithraic cult to the character of the Stoic philosopher Posidonius (c.135–50 B.C). Posidonius was a polymath in realms of philosophy, astronomy, history and many other fields, he was considered the foremost intellectual of his time. He lived in the correct period when the Mithraic mysteries began to emerge and in the Hellenistic world, as he was head of the Stoic school in Tarsus during this era and was the most significant advocate of Aratos’ cosmological and theological ideas.[16]

Consequently, the confluence of factors is remarkable. At the same time, Mithraism in Persia was characterized by astronomy, and the new astronomical cult of Perseus was being formed by Stoicism, who shared the same astrotheological interests as the Mithraic Magi in Parthia as expressed by Aratos of Soli during the same period of first century B.C., in the same city whose patron god was the Hittite Mitra. These factors strike one as a plausible origin point of Hellenic Mithraism. Tarsus was the proverbial Holy See or Mecca of Hellenistic Mithraism, and these Stoic philosophers were the European Magi or priesthood of this cult. A similar phenomenon in the Roman Empire was seen in the relationship between Mithraism and Neoplatonism with philosophers like Porphyry of Tyre who participated in the religious councils spearheaded by the Mithraic priesthood to persecute the Christians. Furthermore, Emperor Julian attempted to mandate Mithraism and Platonism as the religion of Rome to counter the growth of Christianity. Returning to the Hellenistic era, while Tarsus seems to have been ideologically captured by these new Hellenic Mages, the cult of Mithras-Perseus seems to have not spread far outside the city walls of Tarsus and the region of Cilicia and into neighboring Hellenic communities as Cumont relates,

…in spite of all these accomodations, adaptations and interpretations, Mithraism always remained in substance a Mazdaism blended with Chaldeanism, that is to say, essentially a barbarian religion. It certainly was far less Hellenized than the Alexandrian cult of Isis and Serapis, or even that of the Great Mother of Pessinus. For that reason it always seemed unacceptable to the Greek world, from which it continued to be almost completely excluded… The Greeks never admitted the god of their hereditary enemies, and the great centers of Hellenic civilization escaped his influence and…Mithraism passed directly from Asia into the Latin world.[17]

If Mithraism was not a popular religion in the Hellenic world, how did Mithraism, as Cumont states, “passed directly from Asia into the Latin world”? How did Mithra spread to Rome and become so dominant in Rome, even challenging Christianity for the soul of the Roman Empire? Some scholars believe this is where Cumont’s view of Mithraism fails. Their view is that Roman Mithraism originated in Rome, but where did the Romans get the idea of Mithraism, a god worshiped in Persia, India, and PIE Yamnaya culture independently? The Western theory is limited and does not offer enough of an excuse for the Roman origin of Mithras. For example, Roman Catholicism may have been created in Western civilization, but the Christian ideology originates in the Levant from Jewish culture; thus, why should we not see value in Cumont’s thesis of Mithras’ oriental origin? Hence, to answer to this critique of Cumont is in two data points: first, the Cilician Pirates and the wars of King Mithridates VI of Pontus against the Roman Republic, and second was the Roman conquest of the minor Anatolian-Syrian Kingdom of Commagene.

The nature of the Cilician pirates as the ideological vector spread Mithraism from Tarsus to the Greco-Roman world like a Mithraic ghost fleet projecting Iranian religious influence into Greco-Roman civilization. This observation from scholar Jason Reza Jorjani goes one step further and claims that the arrival of Mithra into the Hellenistic world may have been a Kulturkampf or world-view warfare. Thus, the Parthian Empire sought to subvert their ancient Hellenic foes and later Roman civilization by capturing the academic and aristocratic elite with Magian mysticism and astronomy by tapping into the Greek inclination for philosophy, phyusia (physics/physical sciences), or as he puts it “The ‘Persian religion’ of Mithraism was deliberately injected into the continental European Empire of the Romans by their Parthian rivals as a means of psychological warfare and social engineering.”[18] This is a claim that might be dismissed out of hand by unimaginative modern scholars, who might dismiss this idea to the likes of peddling conspiracies. However, as crazy as it may seem, this claim that the Persians/Parthians used religion to combat and convert the Hellenic Kingdoms and later the Roman Empire on a cultural or metaphysical plane is not unreasonable and should be explored. The tactic of cultural subversion is a key factor in psychological warfare from the ancient world to the modern day, and within subversion is the promotion of ideology to undermine your opponent's worldview.[19] Christian and Muslim nations in the medieval period used holy war and aggressive tactics of proselytism to expand their religion’s ideological dominance. Marxist revolutionaries and progressive academics have promoted their ideology clandestinely through the vehicle of education from the Conspiracy of Equals in 1796 to the modern day. Consequently, Jorjani’s claim does not seem unreasonable; as we investigate further, the Cilician pirates were no common thugs but had “established particularly close relationships with the aristocracy and intellectual elite”[20]of Hellenic and later Roman high society. The idea that pirates could be connected to nobility is not farfetched. As demonstrated in Greco-Roman civilization, the notion of an aristocratic pirate is a theme found extensively in Greco-Roman mythology, exemplified and glorified by Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, where the idea of piracy and raiding was a valorized act where heroic warriors lead warbands to prove their Arete (or manly virtue). Reflects the style of Post-Mycenean aristocratic warfare during the era when Homer composed his poetry in the 8th century BC. One could look at Alexander the Great, who embodied the Homeric mindset and had this warrior mentality instilled in him by Plato’s student, the philosopher Aristotle. Building off this theme, the Platonic philosopher and Roman Historian Plutarch of Chaeronea in his Vitum Pompius (the Life of Pompey the Great), illustrates the survival of this Homeric tradition of the aristocrats seeking their fortune on the high seas while referring to the Cilician pirates he states “Presently men whose wealth gave them power, and those whose lineage was illustrious, and those who laid claim to superior intelligence, began to embark on piratical craft and share their enterprises.”[21] The idea of an aristocratic pirate who was well cultured in philosophy is not a stretch as Jorjani relates on the Cilician pirates, “They were known for their strange mix of scientific and intellectual erudition and cut-throat enterprise.”[22] As Mithraic scholar M. J. Vermaseren, in his book, Mithras, the Secret God, concurs by stating, “the pirates, a group of drifting adventurers and, occasionally, fallen noblemen, conducted a communal worship of Mithras, whose cult was an exclusively male one”[23] Mithraism scholars Vermaseren and Ulansey have come to the same conclusion as Jorjani that there is a genuine connection between the Stoic philosophers of Tarsus and the Mithraic believing Cilician pirates as Vermaseren and then Ulansey states,

There are some well-known monuments associated with Mithras in the pirates’ homeland in the mountainous regions of Cilicia, and recently an altar was discovered in Anazarbos which had been consecrated by Marcus Aurelius as ‘Priest and Father of Zeus-Helios-Mithras’[24]

It would, therefore, have been quite possible for the teachings of the young astronomical mystery cult of the Tarsian intellectuals to have been transmitted to the pirates. And note that this is especially true in view of the fact that the pirates, like all sailors, were dependent on the stars for the purposes navigation and would thus very likely have been particularly receptive to religious teachings involving a deity whose essential characteristic was his power over the stars…The cult then spread to the Cilician pirates who had close ties to the wealthy and to intellectuals...[25]

These Stoic-trained aristocratic pirates and their cut-throat crew would find value in the worship of the astral and heroic Mithras, who would naturally fit into their martial existence of raiding, much like how the aristocratic raiders and cattle rustler of the Proto-Indo-Europeans worshiped Mitra as a heroic raider God. Much like these early Aryan warrior societies or *kóryos, the Mithraic Cilician pirates were a communalized and ritualized society of male warriors that adhered to a sense of “inviolable oath of loyalty taken by Mithraists, and enforced by a merciless lord of contracts, would have been appealing to pirates, bands of thieves, or mercenary soldiers”[26], as Jorjani continues,

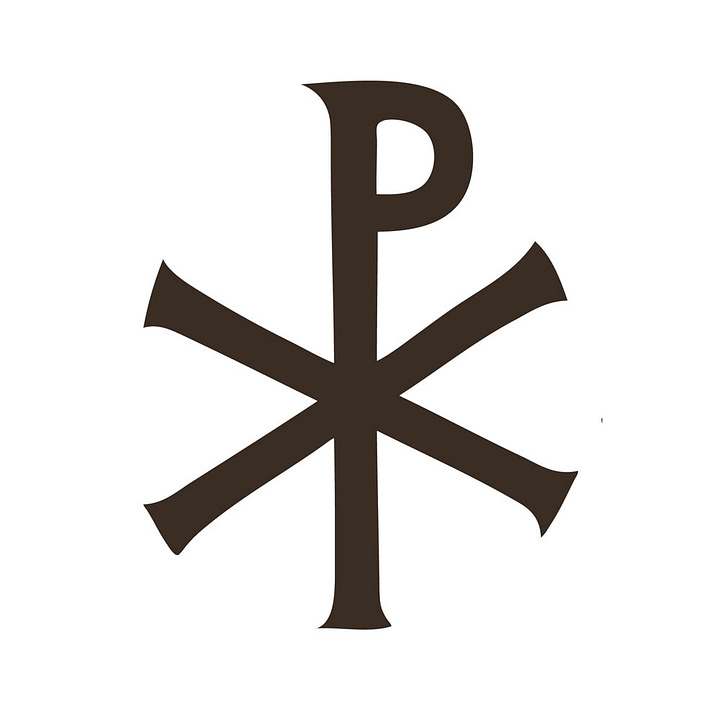

The “Jolly Roger” or skull and crossed-bones pirate flag is Mithraic in origin. The crossed bones represent the Greek letter chi or the X of the intersecting zodiacal circle and celestial equator, and the skull designates this earthly plane of astrologically marked time as the realm of fateful death….the ordeals of being buried alive that the initiate into the first grade of Mithraism, the grade of the Raven, had to undergo in order to transcend this realm of death….In ancient Iran ravens were used for the removal of flesh from an exposed corpse before its bones were placed in an ossuary. The “raven’s head” was the black sediment left at the bottom of an alchemical distillation. It symbolizes the blackness of both putrefaction and primordial chaos. The initiate is made to ingest this putrefaction… The grade of Raven symbolizes the trauma of incarnation into the wetness of worldly existence, which is at the same time a spiritual death.[27]

The Parthian connection to the Cilician pirates is unknown; Jorjani’s concept was plausible, yet in reverse, the Stoics of Tarsus were more likely the origin of Parthian cultural subversion because of their interest in Persian mysticism, while the pirates spread the doctrine of Mithra abroad.

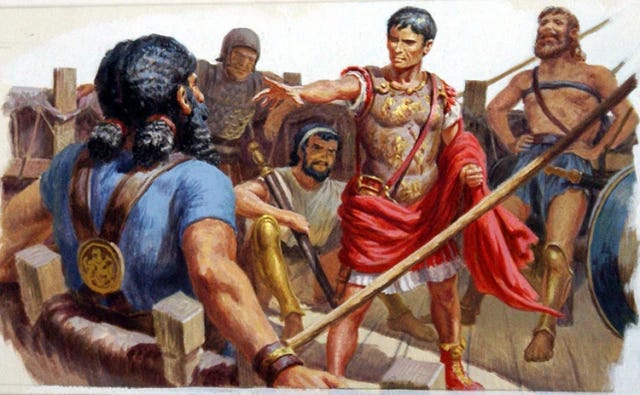

The evangelism of Mithra across the Mediterranean by the pirates was unlike the journeys of St. Paul preaching the Good News, as it was a violent affair. Mithra had his message of cosmic love and divine justice brought by the sword to the Greek world, which had become a battleground for the final series of wars between the Roman Republic and the Hellenistic world to control the Eastern Mediterranean basin. Out of the chaos, the last major Hellenistic ruler from the Kingdom of Pontus rose, the Macedonian-Persian lord Mithridates VI Eupator, as the last significant defender of Greek independence and the Alexandrian legacy. Mithridates would ally with the Mithraic pirates of Tarsus against the encroaching threat of Roman Imperialism. The Mithridatic dynasty created the Pontic Kingdom during the chaos of the Diadochi wars caused by Alexander the Great’s death, as Alexander’s successors were busy fighting each other to notice a Persian dynasty taking root in northern Anatolia.[28] The Mithridatic dynasty claimed descent from the Achaemenid lineage of Cyrus and the accompanying Persian identity. Still, as time progressed, they became more culturally Greek as Pontus became a more prominent player in the Hellenistic world.[29] They adopted the Greek culture and religion of the locals they ruled to complement their hereditary Persian character. They even married into the great families of the Hellenistic Diadochi, showing the origin of Mithridates VI’s claim that he was the genetic heir of both Cyrus and Alexander.[30] Thus, in a sense, Mithridates was the heir of two different branches of the Aryan majesty and Imperial cultures as Philip Matyszak, in his book Mithridates the Great: Rome’s Indomitable Enemy, states

Their coinage shows that the later Mithridatid kings chose to defiantly proclaim their Iranian origins in the face of the current fashion for Hellenization, yet they nevertheless took care to be seen as benevolent rulers who had the best interests of their Greek subjects at heart. Indeed, it was one of the major achievements of the Mithridatid kings that they ruled their kingdom with apparently very little friction between the half-dozen or so major ethnic groups of which it was composed. To the mercantilist, cosmopolitan Greeks of the Black Sea ports, the Mithridatids were civilized monarchs with a Hellenistic court, who sent embassies to Rome, and who made donations and sacrifices to the gods at the Greek sanctuaries. Yet to the people of the interior, many of whom knew little of life outside their own valleys, the Mithridatids were the ancient heirs of the Persian kings, to whom their priests and barons owed unswerving loyalty…Mithridates was for him a king ‘whose greatness was afterwards such that he surpassed all kings in glory – not only those kings of his own times, but of preceding ages too’. Mithridates was well aware of the advantages of what would today be called a personality cult. He deliberately portrayed himself as a fusion of Greek and Persian culture, giving himself the Greek nickname of Eupator, loving father’, and also adopting the title of Dionysius, a god liberty, peace and law; on the other hand, Mithridates habitually dressed in the robes of a Persian noble. He explicitly boasted to his troops that they found in him the best of both worlds. ‘I count my ancestors, on my father’s side, from Cyrus and Darius, the founders of the Persian empire, and on my mother’s side Alexander the Great and Seleucus Nicator, who established the Macedonian empire.[31]

While Mithridates balanced this duality of Gerco-Persian cultural mentalité, the Great King, like his Cilician allies, was a champion of Mithras. While there is an obvious connection to his name, meaning in Greek the “gift of Mithra,” a name discussed in my last paper contemporaneously in vogue in the Parthian Empire of Iran, where Mithraism was the state orthodoxy. Furthermore, Mithridates, like his Parthian counterparts, believed he was a descendant of Perseus.[32] Thus, the Great King used the symbolism of Perseus from Greek myth and portrayed himself as the hero Perseus using both motifs on his coinage, which links him to the Parthian practice of identifying Mithra and the iconography of the mysterious astrological Perseus worshiped by the Stoics of Tarsus.[33] Also, we have the symbolic nature of the Pontic Royal, which symbolizes a star above a crescent moon.[34] This symbol, long before the coming of Islam, has a connection to Mithras. The Parthians used the crescent moon and star symbol for their dynasty because of its Mithraic symbolism.[35] Why would the meaning be any different for Mithridates VI of Pontus to use this symbol of his fidelity to the Stellar Lord or Mithras compared to how Mithridates II of Parthia’s usage to venerate Mithra? There are similarities in the emblem of Mitra sitting above Varuna in the Rig Veda, but as well in the Persian context, Mithra floating over a lotus flower, which represents his Mother, the Persian goddess of fertility, water, healing, and wisdom Anahita, and finally the Yamnaya God*H₂epom Nepōts who was the cosmic fire that rises above the materiality of the waters.[36] Mithra has a solar masculine aspect; to build on this, Anahita takes on a feminine and lunar aspect. Thus, Aryan religions are represented by the solar and masculine as active while lunar and feminine as passive; therefore, based on the aforementioned Mithraic evidence from Hindu and Persian symbolism, the star above a crescent moon symbol represents Mithra’s cosmic ascent from the womb of materiality towards the heaven on a fiery and stellar chariot.

Building on the religious sympathies of Mithridates VI, his Mithraic leanings in the Pontic royal capital of Amaesia as “The great citadel contained both the royal palace a huge altar to Zeus Stratios, whom the Mithridatids identified with Ahura-Mazda, the Iranian fire god and official protector of the dynasty.”[37] This is interesting as it does not just show the Irano-Hellnic syncretism practiced by him and his family but instead hints at the Mithraic character of the worship of this deity, as this god of Zeus Stratios or Zeus Oromasdes, known as Jupiter Dolichenus in the Roman Empire, which has been reasonably linked with the Roman era Mithraic cult. [38] It would be a sufficient assumption that the worship of the Hellenistic Zeus Stratios was linked to Mithras in the Pontic court. In the case of the star above a crescent moon symbol serving as the insignia of his nation and dynasty. The evidence suggests that Mithridates, like his contemporaries in Parthia and the Persian dynasts who ruled the Kingdom of Commagene, worshiped a syncretic Hellenized Mithraic God in the vain of the formulation of “Zeus-Helios-Mithras…Zeus-Ahura-Mazda, Hermes, Apollo-Helios and Herakles-Verethragna” lead by an organized Magian priesthood that had been established in Anatolia since the collapse of the Achaemenid Empire.[39] This personal belief of Mithras by Mithridates VI would explain “that Mithridates had a very strong alliance with the Cilician pirates, whom he used as his allies against Rome…The pirates of Cilicia, therefore, were deeply involved with Mithridates, a great leader named after the Iranian god Mithra.”[40] David Ulansey presents this alliance between the Pirates and Mithridates as the reason why the Tarsus mystery religion became known as the Mithraic cult compared to the being Perseus Cult, as probably Mithridates reintegrated the Iranian tradition back into the Greek mystery religion.[41]

Nevertheless, the Kingdom of Pontus and the Cilician pirates formed a strong anti-Roman front as a bulwark of Greek civilization against barbarian peril. Mithridates as Perseus standing against the titanic threat of the Grogons in the form of Rome, such propaganda was cultivated by Mithridates as the defender of Hellenic liberty to build a collation to support the Pontic bid for a new Alexandrian Empire uniting the Hellenic world under Mithra’s banner. [42]

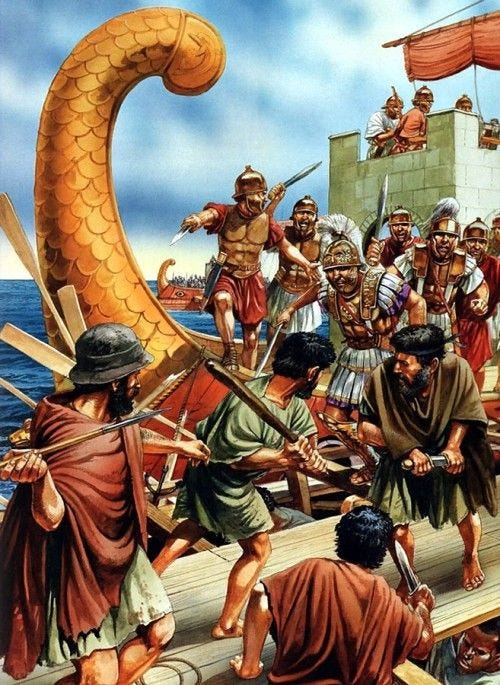

Pontus’ “military and feudal aristocracy furnished Mithradates Eupator a considerable number of the officers who helped him in his long defiance of Rome, and later it defended the threatened independence of Armenia against the enterprises of the Caesars. These warriors worshiped Mithra as the protecting genius of their arms, and this is the reason why Mithra always, even in the Latin world, remained the “invincible” god, the tutelary deity of armies, held in special honor by warriors.”[43] This Mithraic army of Pontus would wage the peer-to-peer war against the legions of Rome, while the Cilician pirates, with a strength of 400 triremes, with the additional number of pentekonter and smaller raiding boats known as lemobi would terrorize the coast of Greece and harassed Roman and Rhodian naval maneuvers preventing the Roman ability to prosecute the land war in Anatolia.[44] This Mithraic alliance divided Roman attention, making the Mithridatic wars more challenging and a protracted conflict compared to Rome’s other wars with other Hellenistic Kingdoms and Empires; as Henry A. Ormerod in his book Piracy in the Ancient World states,

The alliance now formed between Mithradates and the pirates closely resembles the position held by the Barbary corsairs of the sixteenth century under the Sultan of Turkey…The war against the pirates became, in fact identical with the war of against Mithradates…The Cilicians gave Mithradates command of the sea which in the first Mithridatic war was nearly fatal to Sulla.[45]

The Cilician pirates fought zealously against Rome for their co-religionist Mithridates and operated as a fleet of Mithraic and Pontic interests. Mithridates used the pirates as forces to sow discord and aid Rome’s enemies to tie up Roman forces further. The Great King sent a squadron of 81 pirate vessels to aid the rebel Populare General Quintus Sertorius to capture the Balearic islands during a civil war between the Popualre faction led by Gaius Marus the Younger against the Optimate faction led by Lucius Cornelius Sulla, which was busy fighting Mithridates in Asia Minor.[46] Furthermore, we have the anecdote that in 70 BC, during the Third Mithridatic War, a fleet of Cilician corsairs sailed to southern Italy to support Spartacus and his army of slaves and gladiators against Roman forces led by Crassus and Pompey during the Third Servile War.[47]

The Mithraic alliance between Pontus and the Cilician pirates was a tight bond, even after the Romans defeated the Pontic fleet, unlike what one would expect from pirates to cut their losses and abandon Mithridates they did the opposite. The corsairs reformed the Pontic fleet under their banner, thus committing to closer integration with Mithridates, even though the Great King tasked them to defend the city of Sinope.[48] Exhibiting the metaphysical nature of the Mithraic religion as contractual in nature or the divine oaths maintained by a vengeful Mithra that kept the Pirates loyal to their Pontic partners to the bitter end. When Rome finally defeated Mithridates, the Cilicians, honor bound to the struggle, “retreated from the fall of the Pontic Kingdom and occupied Crete which caused a new spike of piracy in favor of Mithradates, making the Roman navy to wage another offensive against the new kingdom of Cilician Crete.”[49] Like their Homeric predecessor, the Cilician Pirates embarked on a piracy campaign that would terrorize the Mediterranean Sea in the name of Mithras for years against the Roman Republic—waging a naval guerrilla war that would flicker on until the Roman Empire finally solidified the Mediterranean under the notion of Mare Nostrum (Our Sea) during the Pax Romano.

However, it was Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, after his defeat of Mithridates VI and his son-in-law Tigranes II the Great of Armenia, moved on to the invasion of Cilicia, capturing the pirate’s homeland, ending the independence of Mithraic Tarsus. During this period, Pompeius Magnus’ grand march down the Eastern Mediterranean, sacking and capturing the Kingdoms of Syria and the Levant, made the fateful decision to vassalize the Kingdom of Commagene in 67 BC.

This often-forgotten Hellenic Kingdom of Commagene, with its capital of Samosata, located in modern Turkey, is located about 180 km or 112 miles from the Mithraic city of Tarsus and, like Pontus, was ruled by a Hellenized Persian dynasty that traced its lineage back to Perseus. The Kingdom was the final area after Cilicia, and Pontus was one of the hypothesized origin points of Roman Mithraism.[50] Commagene is famous in Mithraic studies for the Temple at Mount Nemrud, where we find inscriptions and artwork that are heavily Mithraic inspired, as Vermaseren states,

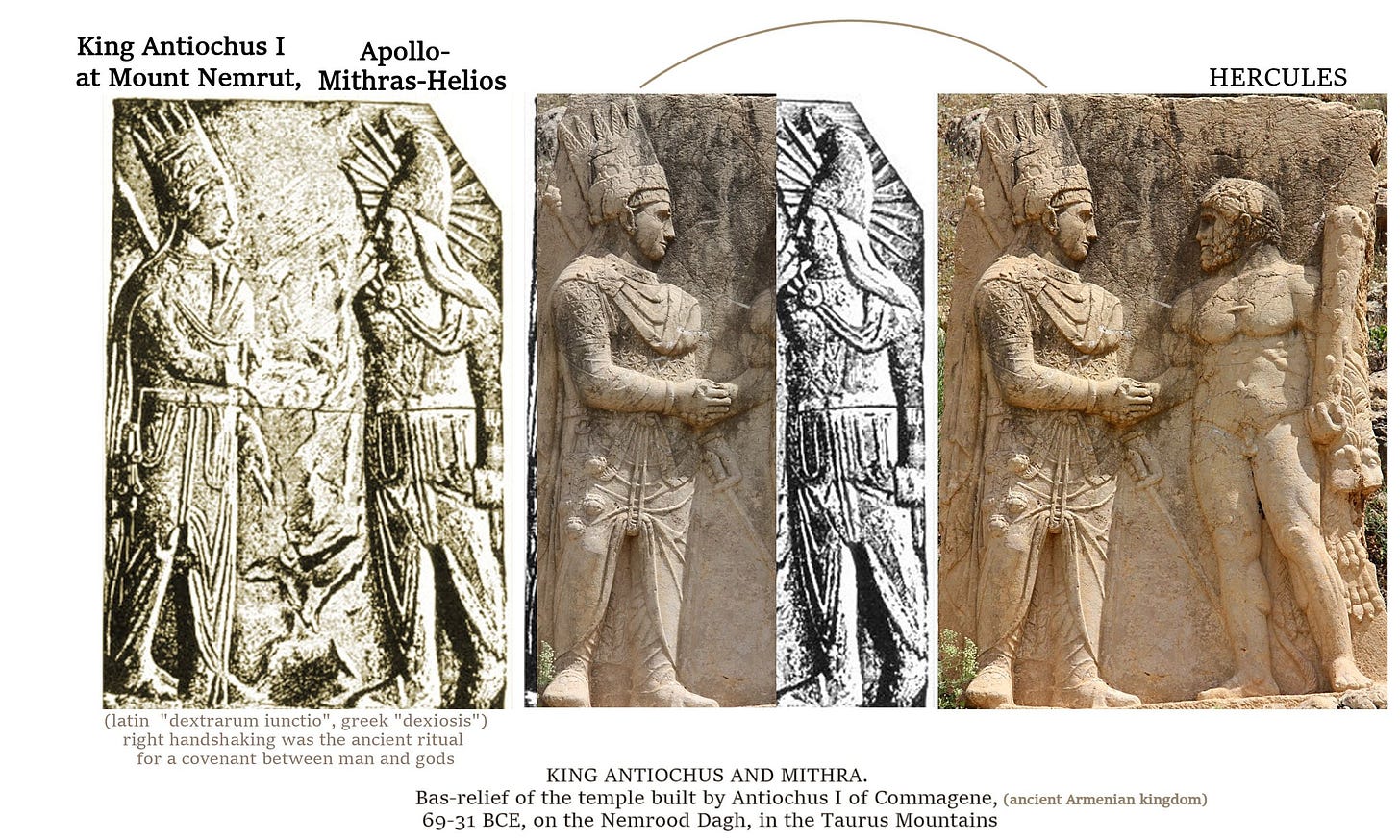

Other early evidence of the first decades b.c. refers only to the reverence paid to Mithras without mentioning the mysteries; examples which may be quoted are the tomb inscriptions of King Antiochus I of Commagene at Nemrud Dagh, and of his father Mithridates at Arsameia on the Orontes. Both kings had erected on vast terraces a number of colossal statues seated on thrones to the honour of their ancestral gods. At Nemrud we find in their midst King Antiochus (69-34 b.c.) and in the inscription Mithras is mentioned together with Zeus-Ahura-Mazda, Hermes, Apollo-Helios and Herakles-Verethragna. Thus Persian gods were invoked as protectors of the royal house. Both Mithridates and his son were represented in reliefs clasping hands with Mithras. Yearly feasts were held in honour of the deceased kings. But the inscriptions do not say anything about a secret cult of Mithras; the god simply takes his place beside the acknowledged state gods.[51]

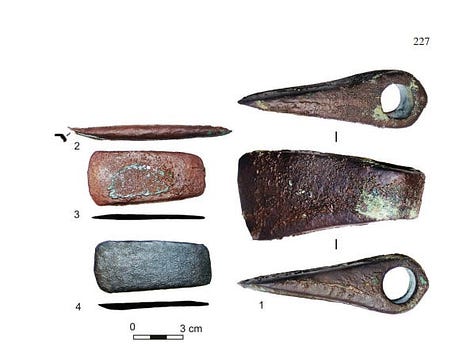

Cumont discusses that the Commagenean royal house, “a half Persian, half Hellenic dynasty succeeded Alexander in Commagene”[52], worshiped a previously mentioned Jupiter Dolichenus (which is another name for Mithras) represented by a double-headed axe as Cumont states, “The ax symbolized the god’s mastery over the lightning which splits asunder the trees of the forest amidst the din of storms.”[53] The symbol of the battle axe is unique but also telling. The double-headed axe or warhammer is a common feature of the Indo-European sky father and the early Aryans; as Julius Evola in his book Revolt Against the Modern World states,

There is a connection between the appearance of the “battle-axe cultures” of the Neolithic and the more recent expansion of the Indo-European populations (“Aryans”) in Europe; they are believed to have originated the political and military institutions and forms of government that opposed the Demetrian, peaceful, communitarian, and priestly type of culture and that often replaced it.[54]

Hyperborean battle-axe and a sign of the thunderbolt force proper to the Uranian gods of the Aryan cycle.[55]

Evola’s connection to primordial Aryan culture is fascinating; as Cumont says, Jupiter Dolichenus is not native to Syria but originated from the north from a tribe of blacksmiths known as the Chalybes who migrated into the area.[56] The ancient Greek writer Apollonius of Rhodes states that the Chalybes were a Scythian group [57]. Thus, as described in my prior papers, showing the Mithraic presence in Scythian religion would further confirm that Jupiter Dolichenus is a Scythian variation of Mithra. A form of a Mithra who got lost in the cultural syncretism of Greek, Persian, and local Semitic culture that was common in the Hellenic East.

With the defeat of Mithridates’ dream of a new Mithraic Alexandrian Empire, the fully formed doctrine of the Hellenic Mithras did not die out. Still, the Lord of Light was adopted by the victorious Romans. The transfer of this new Hellenized Mithra or Mithras into what scholars call Roman Mithraism was a result of the legionary victory over Mithridates and the Cilician pirates under Lucullus and then Pompey along with the vassalage of Commagene as these victories introduced Rome to the ancient influence of Persian culture and subsequently Mithra.[58] Cumont relates, “From these conquests and annexations in Asia Minor and Syria dates the sudden propagation of the Persian mysteries of Mithra in the Occident. For even though a congregation of their votaries seems to have existed at Rome under Pompey as early as 67 B.C.”[59] Mithras was spread throughout the Republic and then Empire by the movement of soldiers, as the Mithraic patronage of soldiers, the keeper of oaths, and destroyer of evil became popular with Pompey’s legionaries who carried this faith home with them. The legions would spread Mithras across the Empire across Europe and into Africa down to the Sahra desert.[60] Additionally, Cumont states that Persian and Greek slaves from the eastern provinces spread the faith passively as the Roman state had them “engaging in every pursuit, employed in the public service as well as in domestic work, in the cultivation of land as well as in financial and mining enterprises, and above all in the imperial service, where they filled the offices.”[61] This matches with the famous quote of Plutarch in Mithraic scholarship discussing a group of Cilician pirates deported and resettled in Greece by Pompey after the defeat of Mithridates, as Plutarch states, “They also offered strange sacrifices of their own at Olympus, and celebrated there certain secret rites, among which those of Mithras continue to the present time, having been first instituted by them.”[62] Mithras found an equally warlike people as the Macedonians and Persians to carry his banner onward into the future. Thus, the irony of the defeat of Mithridates and the Cilician pirates allowed Mithras to make the transition to patronize and convert a larger Empire that held sway over a large portion of the Aryans of Europe, that being Rome, the new defender of Greco-Roman civilization against the barbarity beyond her borders. The exploration of how Mithras converted Rome and nearly became the religion of the West will be the topic of the following paper in my series on the History of Mithraism. (Continue Below)

Mithra, The Hidden Sun of The Aryans Part 4: Roman Mithraism

The study of Mithra, as examined throughout my Substack, has assessed the anthropology of a God and his cultural interactions with various Indo-European peoples from the Bronze Age forward. This will be the first in a series of papers examining multiple aspects of the Mithraic Cult during the Roman Empire. Yet, this is the conclusion paper in my series …

Bibliography

Apollonius of Rhodes . Argonautica. Translated by R L Hunter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Clauss, Clauss Manfred. Roman Cult of Mithras. Edinburgh University Press, 2019.

Colledge, Malcolm A.R. The Parthians: Ancient Peoples and Places. Thames and Hudson, 1967.

Cumont, Franz . The Oriental Religions in Roman Paganism. Chicago : Open Court Publishing, 1911.

Evola, Julius. Revolt against the Modern World. Translated by Guido Stucco. Rochester, Vt.: Inner Traditions International, 1995.

Gershevitch, Ilya , trans. The Avestan Hymn to Mithra. Cambridge University Press, 1967.

Jorjani, Jason Reza. Iranian Leviathan : A Monumental History of Mithra’s Abode. London: Arktos Media Ltd, 2019.

Matyszak, Philip. Mithridates the Great. Pen and Sword, 2009.

Ormerod, Henry Arderne. Piracy in the Ancient World. 1924. Reprint, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

Plutarch. Plutarch: Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans : [Complete and Unabridged]. Translated by Arthur Hugh Clough. Oxford: Benediction Classics, 2015.

Puhvel, Jaan . Comparative Mythology. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987.

Strabo. The Geography of Strabo. Translated by Horace Leonard Jones. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1929.

Ulansey, David. The Origins of the Mithraic Mysteries : Cosmology and Salvation in the Ancient World. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Vermaseren, Maarten Jozef. Mithras, the Secret God. New York : Barnes & Noble, 1963.

[1] Jason Reza Jorjani, Iranian Leviathan : A Monumental History of Mithra’s Abode (London: Arktos Media Ltd, 2019),166.

[2] Ibid 166-7

[3] Malcolm A.R. Colledge, The Parthians (Praeger, 1967), 108.

[4] Colledge, 102-3.

[5] Franz Cumont, The Oriental Religions in Roman Paganism (Chicago : Open Court Publishing, 1911),142-4.

[6] Cumont. 145

[7] David Ulansey, The Origins of the Mithraic Mysteries : Cosmology and Salvation in the Ancient World (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 68.

[8] Strabo, The Geography of Strabo, trans. Horace Leonard Jones (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1929), vol. 6, p. 347.

[9] Chaldea is an nebulous term used to define what the Greeks and Roman understood as Babylonian and Persian culture. Hence Chaldean mysteries where to the Ancient Greeks a tradition of mixed Semitic and Iranian magic and philosophy that was erroneously designated to be a coherent modality by the Hellenistic age and the Roman Empire

[10] Ulansey, 69.

[11] Šanada is depicted in Apollonian terms associated with archery and plagues, hinting the connection to Hittie deity, Apaliunus who in the first paper in this series on Mithra, we connected Apaliunus to the same divine participation as Mitra/Mithra.

[12] Ulansey, 93.

[13] Cumont, 145-6.

[14] Cumont,148-9.

[15] Maarten Jozef Vermaseren, Mithras, the Secret God (New York : Barnes & Noble, 1963), 27.

[16] Ulansey, 73.

[17] Cumont, 148-9.

[18] Jojani,172-3.

[19] https://www.usmcu.edu/Outreach/Marine-Corps-University-Press/Expeditions-with-MCUP-digital-journal/To-Win-without-Fighting/

[20] Ibid 172

[21] Plutarch, Plutarch: Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans : [Complete and Unabridged], trans. Arthur Hugh Clough (Oxford: Benediction Classics, 2015). Vita Pompei.24.2

[22] Jorjani, 172.

[23] Vermaseren, 27-8.

[24] Ibid

[25] Ulansey, 88-94.

[26] Jorjani, 172.

[27] Ibid, 173.

[28] Philip Matyszak, Mithridates the Great (Pen and Sword, 2009), 1-2.

[29] Bosworth, Wheatley, ‘The Origins of the Pontic House’, in The Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol 118 (1998), PP 155–164.

[30] Matyszak,1-4.

[31] Ibid, 3-8.

[32] Ulansey, 94.

[33] Ulansey, 89-90.

[34] Matyszak, 3.

[35] Jorjani, 166.

[36] Jaan Puhvel, Comparative Mythology (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987), 227/ Ilya Gershevitch, trans., The Avestan Hymn to Mithra (Cambridge University Press, 1967), 6-7.

[37] Matyszak, 9.

[38] Clauss Manfred Clauss, Roman Cult of Mithras (Edinburgh University Press, 2019), 44.

[39] Vermaseren, 27-8. Cumont, 144.

[40] Ulansey, 89.

[41] Ulansey, 90.

[42] Matyszak, 18.

[43] Cumont, 144.

[44] Henry Arderne Ormerod, Piracy in the Ancient World (1924; repr., Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), 211-2, 220.

[45] Ormerod, 209-12.

[46] Ormerod, 223.

[47] Ibid

[48] Ibid, 223.

[49] Ibid, 225-7.

[50] Cumont, 137.

[51] Vermaseren, 27-8.

[52] Cumont, 145-8.

[53] Ibid

[54] Julius Evola, Revolt against the Modern World, trans. Guido Stucco (Rochester, Vt.: Inner Traditions International, 1995), 231.

[55] Ibid, 292.

[56] Cumont, 145-8.

[57] Apollonius of Rhodes , Argonautica, trans. R L Hunter (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015) pp. 49, 65.

[58] Cumont, 139-40

[59] ibid

[60] Ibid, 149

[61] ibid

[62] Plutarch vita Pompey.24.5

Parvaneh Pourshariati, Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran, 359