Mithra the Hidden Sun of the Aryans Part 2: Persian Civilization

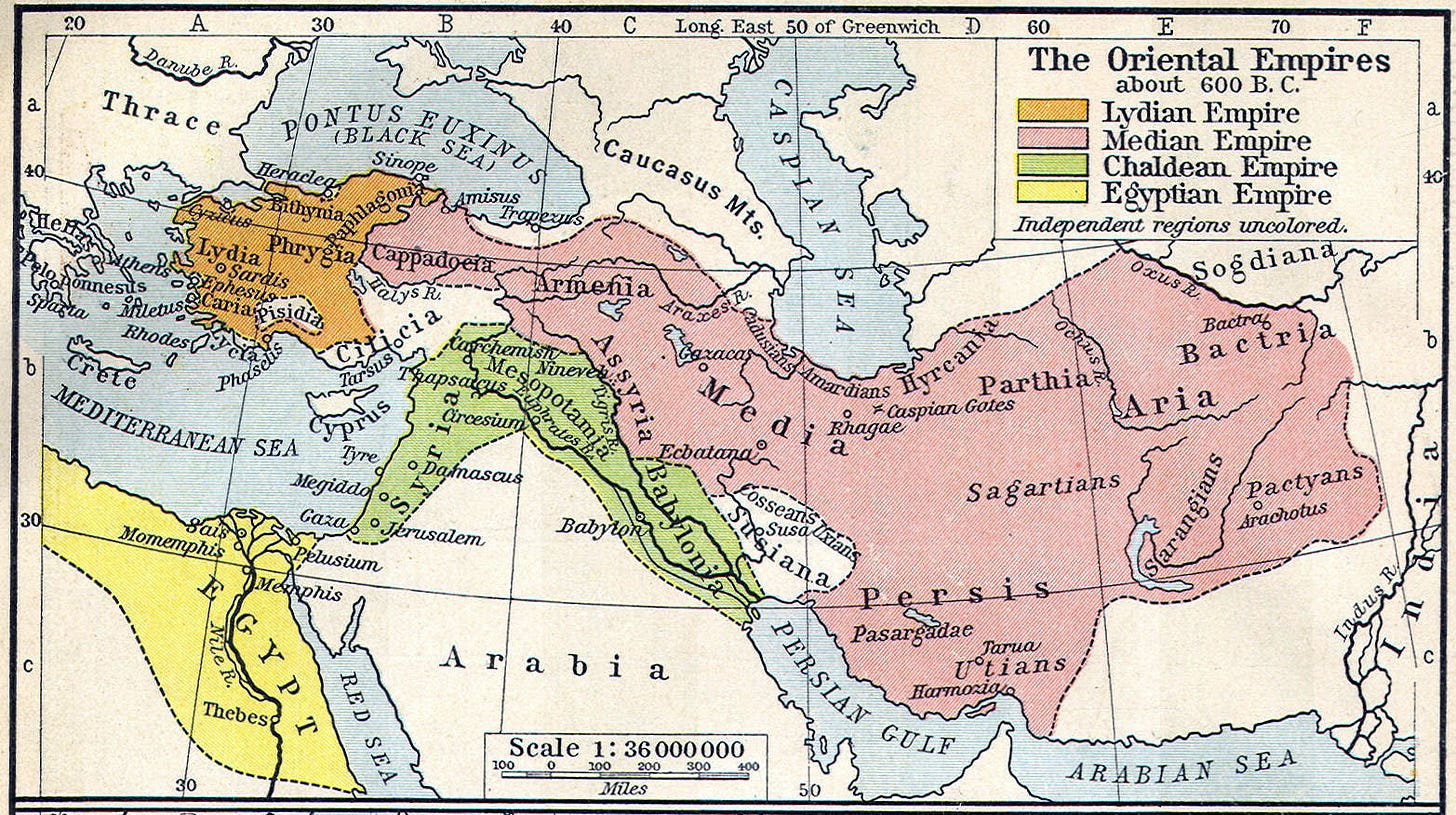

From The Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex to the Fall of the Sassanid Empire

Part 1: Mithra’s Arrival in Iran, Zarathustra, and Persian History Pre-Cyrus II

The story of Mithras in the Persian context is a long story that highlights the intertwined and complex relationship between Mithra and the Iranian peoples, from the Bronze Age Aryan migration into the Iranian Plateau to the Fall of Iran to the Caliphate. To begin the next chapter of this story, we must step backward and start in the Bronze Age. Like his Hindu equivalent, Mitra, Mithra was one of the essential primordial gods of the emergent Iranic peoples of Persians, Medians, and Scythians races. However, like the primordial Mithras discussed in the first paper, there was no racial, cultural, or theological difference between the Iranic and Vedic Aryans, as scholars identify them as Indo-Aryan or Indo-Iranic peoples. As the Eastern Aryans left the Indo-European homeland, we see the formation of the Sinstashta culture and, more relevant the Andronovo cultures that migrated out of modern Russia south toward Central Asia evolved into a new cultural entity scholastically known as the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex, which was the nomadic vector that brought Mithra into Central Asia. The Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex, or BMAC, located in modern Turkmenistan and Northern Afghanistan, was like the prior Yamnaya, Sinstashta, and Andronovo cultures, which were a semi-nomadic Indo tribe. However, the departure of the BMAC Aryans from modern Afghanistan would cause this proto-nation of the Indo-Aryan peoples to divide into two groups of Iranic nations that migrated west into modern Iran and Vedic peoples who moved east into modern Pakistan and India. According to one hypothesis, the reason for the split was that proto-Iranian groups may have overpowered the proto-Vedic Aryans, pushing them further eastward into the Indian subcontinent. This conflict is thought to be reflected in the opposing religious interpretations of the same deities. In the Vedic tradition, the term Deva refers to benevolent gods, such as Indra and Agni, while the Iranian counterpart, Daeva, came to mean demonic beings—essentially “false gods.” Conversely, Zoroastrians revered the Asuras (like Ahura Mazda, the supreme deity in Zoroastrianism) as benevolent, yet the Vedic Aryans considered asuras a class of antagonistic, often demonic, entities. This dualistic religious opposition suggests a cultural rift, possibly stemming from a historical clash or competition for territory between these early groups.1

These early Iranic peoples would further subdivide into Persians, Medians, and Scythians. All these peoples venerated Mithra, making Mithraism the first established religion of the Iranians and the first national faith of Persia long before the coming of the monotheistic revolution of Zoroastrianism.[1] These proto-Iranian peoples would champion Mithra, god of war, lord of vast pastures, the open air, the sun, and the guardian of the cosmic order and contracts, and among first among the panoply of Indo-European gods or Iranian polytheism that was established in Iran the, as A.T. Olmstead in his work History Of The Persian Empire states,

Second only to the all-embracing sky was Mithra, worshiped long since by fellow-Iranians in Mitanni and by other Aryans in India. Like all the Iranian Yazatas, he was a god of the open air. In one of his numerous manifestations, he was the Sun himself, in modern proverb the “poor man’s friend,” so welcome after the cold nights of winter, so terrible in summer when all vegetation parched. Other passages connect him with the night sky. Again, he was first of the gods, the Dawn, who appeared over Hara, Mount Alborz, before the undying swift-horsed Sun; he was therefore the first to climb the beautiful gold-adorned heights from which he looked down upon all the mighty Aryan countries that owed to him their peace and well-being. But it was as the war-god that Mithra was most vigorously and most picturesquely invoked by the still untamed Aryans...By force they had won the plateau and by force they had to defend it against the aborigines. The hymn devoted to Mithra pictures the peaceful herdsmen attacked by flights of eagle- feathered arrows shot from well-bent bows, of sharp spears affixed to long shafts, and of slingstones, and by daggers and clubs of the Mediterranean type. Even more dangerous were the spells sent against them by the followers of the Magi. We see the bodies pierced, the bones crushed, and the villages laid waste, while the cattle are dragged beside the victor’s chariot into captivity in the gorges occupied by the opponents of Mithra. The hymn continues, as the lords of the land invoke Mithra when ready to march out against the bloodthirsty foe, drawn up for battle on the border between the two contending lands.[2]

The original cult of Mithra worshiped Mithra and Indo-European Gods in nature without the need for temples like the Yamnaya; as the Greek historian Strabo, in his work Geographica, states,

The Persians therefore do not erect statues and altars, but sacrifice on a high place, regarding the heaven as Zeus; and they honour also the sun, whom they call Mithra, and the moon and Aphrodite and fire and earth and the winds and water.[3]

Hinting at the original celestial nature or astrotheology, they categorized Mithra’s worship in the Proto-Indo-European homeland. Mithra became the lord of the warlike Aryans of Iran who had not settled into an urban life, such as the Scythians.[4] Furthermore, Mithra and his theology would define the Aryan mentalité of just or holy war for the Iranians that guided Irani warrior cultures from this early period into the Persian Imperial age of the Achaemenids, Parthians, Sassanid dynasties. Thus, the concept of the holy war became the moral imperative of fighting against the forces of evil, such as demons, oath breakers, and chaos, depicted as the Aryan archetype of the holy warrior slaying the encomisc dragon of the Chaoskampf [5] as Julius Evola in Metaphysics of War states,

The Iranian tradition also includes the symbolic conception of a divine figure -Mithra, described as‘the warrior who never sleeps’ – who, at the head of his faithful Fravashi, fights against the emissaries of the dark god until the coming of the Saoshyant, Lord of the future kingdom of ‘triumphant’ peace. [6]

With the arrival of the Iranian people on the Persian plateau, their new prospective home was a land torn apart from conflict. The Neo-Assyrian Empire had launched a period of genocidal imperial conquests that spread across the Near East. These wars had the consequences of decimating the local pre-Iranian polity of Elam that dominated the south of modern Iran, massacring and enslaving the population. The collapse of Elam because of the brutality of the Assyrian invasion permitted the Aryans, known as Medes and as well early Persians, to spread out and colonize the country without much pushback from the Elamite locals who had lost all civilizational cohesion. The Assyrians would attempt to subdue the newly established Medes, but with little effect; the combination of Iran’s mountainous topography, nomadic lifestyle, and warrior culture made the Aryans a formidable opponent to subdue. The newly formed kingdom of the Medes would be victorious in defeating the Assyrian invasion of their kingdom. However, following a military campaign around 653 BCE, the Scythians, the Medes nomadic cousins, gained control over large parts of the Iranian plateau, establishing dominance over the Median Empire and forcing the Medes to pay tribute for nearly three decades. The Greek historian Herodotus describes this period of Scythian rule as marked by frequent raids, pillaging, and a nomadic style of governance that profoundly affected the region’s politics and culture. Herodotus attributes the incursion to the Scythian king Madyes, who is said to have led the campaign that subdued the Medes, extending Scythian influence as far south as Egypt (Histories, Book 1.95–144 ). The Scythians, unlike their Median and early Persian cousins, still maintained the original Mithraic cult of nocturnal bull and horse sacrifice dedicated to Mithra.[7] This Sythcian occupation was a significant factor in the growing religious difference between the Mede-Persians and the Scythians, which would become a source of conflict between brother races. The Median nation, led by its nobility, was experiencing a religious transition from the early Mithraic cult of the Yamnaya and Indo-European/Iranian polytheism to the formulation of a new monotheism belief. As tradition holds, a Mithraic priest or Magi somewhere in Greater Iran (probably in Northeastern Iran or Afghanistan) named Zarathustra had a vision of the One true God, and thus he sought to redefine the faith of the Iranian people under the singular lord of Ahura Mazada to eliminate all other of the old Aryan Gods including Mithra as Olmstead states,

Other divinities from dim Indo-European times — the sun-god Mithra, for example — might be cherished by kings and people, but to Zoroaster these daevas were no gods but demons worshiped by the followers of the Lie. Ahura-Mazdah was in no need of minor divinities over whom to rule as divine king.[8]

As stated in my last paper, the Mithraic cult, with its wolf-like attributes, is associated with the Aryan warrior caste or the Wolf warrior/Koryos of the Yamnaya. This wolfish mentalité, once the sign of the solar divinity, was shifted by Zarathustra to symbolize the essence of Ahriman, the source of ultimate evil. I would argue that Zarathustra’s religious reforms were meant to supplant the existing and ruling warrior-dominated Mithraic cult with a new priestly ruling caste accountable to a new religious priesthood that benefited him personally, which could explain Mithra’s transition from a core deity to a demon. Thus, the spiritual landscape of Iran became a powder keg as Zarathustra worked tirelessly to promote his new monotheist program, creating significant divisions between the Aryans of Greater Iran. Zarathustra began petitioning the Medes and early Persians to shed many aspects of their primordial faith, such as banning blood sacrifice and the heroic and shamanic Homa ritual, which angered the traditional Mithraic establishment.[9] The banning of the Mithra cult was not a popular act for the Aryan inhabitants of Greater Iran, just like the Christian schism in early modern Europe between Catholic and Protestant faiths. The Mazdean theological revolution sought the expulsion of the traditional Indo-European gods, Mithra included. This was poorly received by the northern nomadic Irani tribes, sociologically in the ranks of nobility and the ruling Scythian caste.[10] This division sparked a violent schism between the followers of Zarathustra and the Mithra cult, causing a Zoroastrian-Median revolt against the Mithraic Scythians. This war evolved from a typical noble revolt into a religious and sectarian war between two brother nations divided by faith, as Jorjani states.

The conflict between Zoroastrianism and an older Mithraic worldview that evolves in response to Zoroastrianism is not a matter of mere tribalism, it is a fundamental philosophical clash. Zoroastrianism was not only opposed by one single religious or philosophical rival. It was opposed by the Scythian Magic that the message of Zarathustra was directed against.[11]

Traditionally, this conflict is remembered in the Iranian cultural sphere as Persian-Turan war from the medieval Iranian Epic of the Shâhnâmeh (which is the source of pre-Islamic Aryan Persian mythology/pre-history, much like Beowulf or the Nibelungenlied that were Germanic Aryan stories that were framed in a Christian narrative), that provides a mythological retelling of the Median-Scythian War of the 7th century BC, exemplified through the mythological heroic duel of the Scythian Rostom and the Persian Esfandiyar. This war was a religious crusade of the Zoroastrian Medians against their Mithraic Scythian overlords that would decide the fate of Iran. This conflict would see Zarathustra as a martyr to a Scythian raid, as Jason Reza Jorjani's Iranian Leviathan: A Monumental History of Mithra's Abode states,

Zarathustra’s revolution is a conflict between the Medes and the Scythians, who had helped the Medes defeat the Assyrians but were then betrayed. At this time, the Persians were already vassals of the Medes and for all we know Zarathustra himself was a Persian…these antagonists are Scythian Mithraic magicians and semi-nomadic warriors who would terrorize the settled Medes. The epic war between Iran and Turan in the Shâhnâmeh is the Median-Scythian War of the seventh century BC. Once the Median Magi were converted to Zoroastrianism, this was an ideological crusade of the Medians against Scythian paganism. It is the war in the context of which Esfandiyar distinguishes himself as the leading commander, and the war that eventually claims Zarathustra’s life during a Turanian, i.e. Scythian, invasion of the northeastern territory of the Median Kingdom.[12]

The Median-Scythian war would allow the Medians to achieve independence from their Scythian overlords despite the death of their prophet, Zarathustra. As the new Median King Cyaxares, in seeking détente with his Scythian foes, including King Maydes, invited them to a dinner party where he got the Scythians drunk and cowardly murdered them all. This act of treachery allowed Cyaxares to assert Median independence and hegemony across the Iranian plateau. However, this period of Scythian rule reintroduced Mithra to a primary role of Medians and Persian Iranian polytheism. The absorption of the Saka into the Median Kingdom resulted in the genetic and ideological impression reintroducing the profound influence of Mithra on the Persian religion until the Islamic conquest. The conclusion of this war saw the Median Kingdom expand into Anatolia only concluded after the peace deal signed with the emergent fellow Indo-European Lydian Kingdom after the battle of “the eclipse” or the Halys River. The final campaign of Cyaxares would see war re-erupt with their Scythian cousins would drive the Scythians out of Greater Iran to where they would resettle in modern-day Ukraine and Southern Russia, completing the project of forcible conversions of the Aryans of Greater Iran to Zoroastrianism.[13]

Part 2: The Achaemenid dynasty

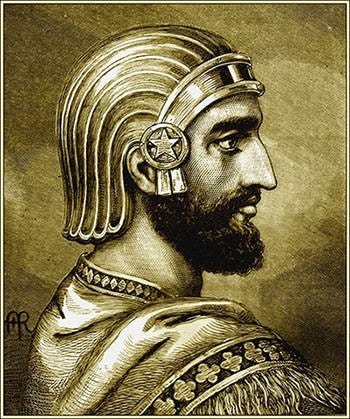

Notwithstanding Zarathustra’s monotheistic ambition, Mithra could not be entirely expunged from the Aryan heart, as with the rise of the Persians in toppling the Medians by Cyaxares grandson, Cyrus II Shah of Persia. The rise of Cyrus seems to hail a return of Mithra as returned lord of the land and Zoroastrianism to be marginalized from royal favor. The Achaemenid dynasty, founded by Cyrus, seems to have had an ambivalent relationship with Zoroastrianism. While Cyrus may have tolerated Zoroastrianism, it is more likely that he was a follower of Mithra, and many of the Medians, such as the General Harpagus, who helped Cyrus overthrow his maternal grandfather Cyaxares, were as well Mithraist, hinting at a counter-revolutionary movement to restore the old Mithraic faith.[14] Cyrus was historically quite tolerant of all the faiths of the lands he conquered and provided an ecumenical status that his people were not tied to the Zoroastrian faith. Among this sense of tolerance of Padishah Cyrus, he was particularly keen about the God Apollo worshiped by his Greek and Lydian subjects whom he saw as affinity with his own Mithra worship, as Jorajani relates,

Those Median priests who accompanied him, and officiated the new cult, even called themselves karapans — the same title as the old Indo-Iranian sacrificial priests demonized by Zarathustra in the Gathas. Interestingly, while the Aramaic version of an inscription from the Mithraic cult at Xanthus refers to Mithra as Khshathrapati, the Greek version of the same inscription refers to Apollo. Cyrus honored many foreign gods, but his exceptionally great respect for the Greek god Apollo has been seen by some scholars as indicative of his recognition of Apollo as a Hellenic equivalent of his own patron solar deity, namely Mithra.[15]

Beyond this seemingly circumstantial evidence, solar and Mithraic imagery dominates the iconography of the Padishah’s reign, such as the recurrence of numerology and celestial religion or what the Platonists associated with the Magi that worship Mithra.[16] Such a cosmological example of divine numerology was 360, which is associated with the days of sunlight(in the Persian calendar) and symbolizes the razes of the sun, a number that repeats throughout the life of Cyrus. Such as 360 channels created to divert the waters of the Euphrates River or the ceremonial assembly of 360 white horses to mimic Mithra’s chariot during the same siege of Babylon.[17] Beyond the limited historical information we have on Cyrus the Great’s life, we can imagine that the Padishah sought to restore the solar orientation of Mithra to the Persian Empire as his Scythian cousins had attempted prior. Still, we lack any sense that the Padishah attempted to suppress the faith of Zarathustra. To conclude on the great Padishah, we shall quote Jorajani on his conclusion on his evidence of Cyrus’ Mithraic tendencies by highlighting the un-Zoroastrian nature of his burial, as he continues,

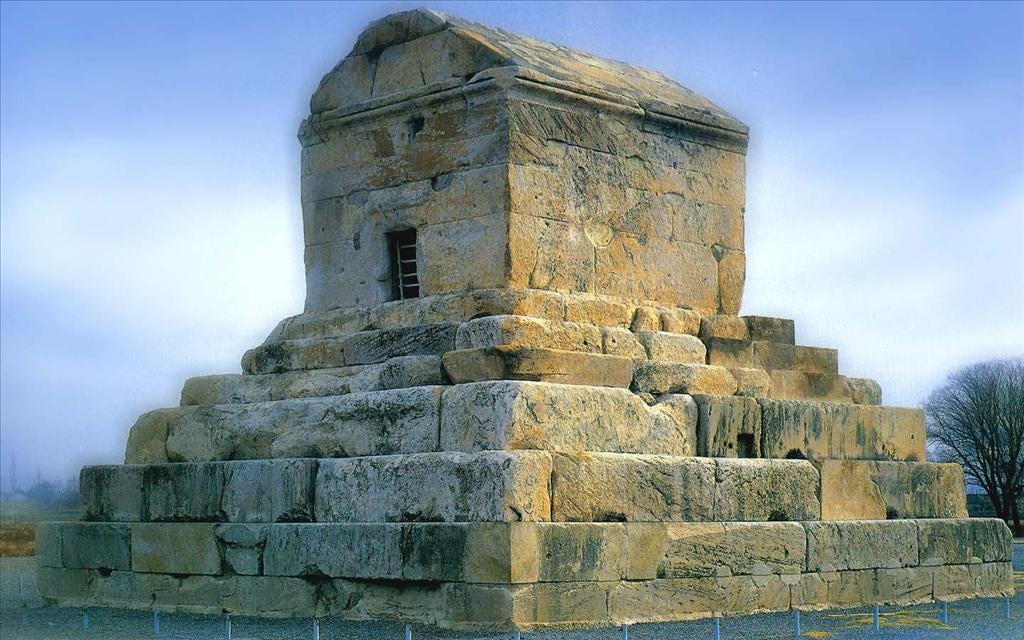

Perhaps the single most significant piece of evidence in favor of Cyrus being a Mithraist, and not a Zoroastrian, are the horse sacrifices that were carried out on a monthly basis at his tomb in Pasargadae. Zarathustra vehemently opposed any form of animal sacrifice, and harming horses is considered a particularly heinous offense by Zoroastrians. The floral design engraved on the tomb of Cyrus the Great, which is the only image or motif present on the titanic stone structure, is also Mithraic in nature. It depicts a hybrid of the sun and a lotus flower. A symbol nearly identical to this one shows up in later Iranian rock carvings of Mithra wherein the god is standing on such a solar lotus, while holding a barsom or “fasces.”[18]

Cyrus’ heir, the Padishah Cambyses, who took the throne as co-ruler with his father in 530BC, was like his father before him, was a Mithraist and seemly continued his father’s policies until his premature death in 522BC.[19] He was succeeded by his brother Bardiya, the satrap of Bactria (modern Afghanistan), who, according to the Greek historian Herodotus, was murdered by a Magi who impersonated the Shah and ruled as a tyrant. Then the story continues that the Zoroastrian faithful nobleman and family relative, Prince Darius, with a band of warriors, broke into the palace and killed the false Bardiya, with Darius becoming the new Padishah. This episode of the brief rule of a mostly forgotten Persian monarch is significant as a renegade Magi never overthrew Bardiya; instead, the Magi that Darius killed was likely Bardiya, the head of the Mithra cult. This hints at an ideologically motivated regime change as the slaughter of Shah Bardiya and the Magi, which was remembered in the Persian Empire as the festival Magophonia. As we can see after the death of Bardiya, the Empire takes on a more Zoroastrian character, and inscriptions of Mithra seem to disappear as it “is significant of an earlier source that he actually ascribes the listing of the six forms of contract to Ahuramazda, whom Darius had long since announced as the true divine author of his own law.”[20]

The worship of Mithra seems to have been banned again during the Persian Empire until the reign of Artaxerxes II; despite the ban on Mithra, the manifestation of Mithraic aesthetics survived in Persian culture in the Zoroastrian period.[21] Such as the celebrations, such as the King's birthday and Mithraic holidays, were marked by distinctive rituals, including the Persikon or Shield Dance, which has evolved into the modern Pahlevani and zourkhaneh rituals. This ancient dance resembles the Dorion Greek war dance known as Pyrrhichios and the mythical Corybantian dance done to protect infant Zeus. Furthermore, Greek sources tell of the continued importance of Mithra as Iranian historian Parvaneh Pourshariati, in her book Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran, states,

Xenophon informs us in both Anabasis as well as Cyropaedia that “the Persian king swore by Mithra.”…And finally both Aelian and Pseudo-Callisthenes note that “the [king?] swore by Mithra. The implication of all this is that “most, if not all, Iranians swore by Mithra, and not just the king or the army.”2

Moreover, the Mithraic festivals in Persia were characterized by elements such as heavy drinking as the Greek historian Ctesias, as quoted by Athenaeus of Naucratis, states,

Ktesias reports that among the Indians it was not lawful for the king to drink to excess. Among the Persians however the king was permitted to be intoxicated on the one day on which sacrifice was offered to Mithra.[22]

These kinds of religious rituals of excessive drinking are comparable to Dionysian rituals in Greece. As well the prevalence of Mithraic-inspired equestrian activities reminiscent of celebrations associated with old Aryan nomadic traditions, as Duris of Samous, as quoted by Athenaeus of Naucratis, states,

In the seventh book of his Histories Duris has preserved the following account on this subject. Only at the festival celebrated by the Persians in honour of Mithra does the Persian king become drunken and dance after the Persian manner. On this day throughout Asia all abstain from the dance. For the Persians are taught both horsemanship and dancing ; and they believe that the practice of these rhythmical movements strengthens and disciplines the body.[23]

Furthermore, the presence of Mithraic names in the courts of rulers like Darius and Xerxes indicates the significant cultural influence of Mithras within the Persian nobility. Additionally, as well Mithra provided the Farrnah or Far of the divine right of kings, as Jorjani expands on,

Farr was also thought to be embodied by birds of prey, such as the eagle that nursed Achaemenes, the patriarch of the Achaemenid clan that includes Cyrus, Darius, and Xerxes. Whether Iranians accepted or rejected a monarch’s sovereign authority over them depended on their perception of whether or not that monarch possessed the Farr. Ancient Iranians believed that Farr could be possessed — or for that matter lost — not only by individuals, but by whole tribes and nations.[24]

While Mithra’s cultural influence was strong, he was theologically minimized to the function of an Amentas Spenta or an aspect of Ahura Mazda, with his cult made heretical for many generations. In an exciting turn of events, the coming of the new Shah Artaxerxes II’s reign saw the restoration of Mithra. Still, his restoration was based on a legitimacy problem or a lack of divine Far. As observed in his reign was a series of noble revolts challenging the autocratic authority of the Achaemenid dynasty, starting with the revolt of his younger brother Cyrus the Younger, culminating in the battle of Cunaxa 401 BC as recorded by the student of Socrates and Hoplite present at the battle, Xenophon in his Anabasis. However, this was not the end, as the Great Satrapial Revolts plagued the imperium, which dominated Artaxerxes rule in the 360s and 350s BC.

Artaxerxes II's rule, rocked by internal strife, needed a method to foster political unity and stability in a diverse Empire. He decided to bring in the Persian and Median populations as a reliably loyal power base and restore the Far or his reign simultaneously. The Shah’s solution was to rehabilitate the worship of Mithra as a means to foster political loyalty and cultural continuity with his Irani core of the Empire, thus binding the Iranian nobility to the monarchy's survival with Mithra, the lord of oaths and the guarantor of monarchal legitimacy. While the new Shah did not restore the Mithra to his ancient primacy as Cyrus the Great did, the primordial popularity of Mithra with the Medes and Persians made Artaxerxes seek a synthesis between Zoroastrianism and Mithraism. A new imperial orthodoxy that sought to balance the metaphysical struggle between Mithra and Zarathustra that had affected Median-Persian culture since the beginning. The Shah made Mithra and his mother Anahita equal in a solar trinity with Ahura Mazda, a sort of divine family as seen in inscriptions from Artaxerxes II’s reign: “Ahura Mazda, Anahita, and Mithra protect me against all evil.”[25] Also, the ancient Aryan oral wisdom of Mithra was written down during Artaxerxes II's reign in the Hymns to Mithra, which was added to the Avestan canon, where Mithra was reconfirmed in his role as lord of oaths, light, cattle, and war but was further granted the role as the cosmic mediator between good and evil within the Zoroastrian framework.[26] As well, Zoroastrian temples were known as “Dar-e Mehr” or gate of Mithra, not to mention the presence of Mithra ritualism survived, such as the Homa ritual and the Bullhead mace of Mithra that initiated the Mazdean priests.[27] As well Mithra also claimed the seventh month named Mehr of Persian Calander, which is September to October, and the festival of the longest night or Yaldâ, which correspondences to the winter solstice (which, if we account for the Gregorian calendar reforms accounting for the subtle drift of the equinox is the 25th of December) that sees the rebirth of the Sun.[28] Mithraism, despite attempts to crush it, was a foundational feature of ancient Persian culture and became an integral part of Zoroastrianism, with Mithra as a Yazata and as the greatest disciple of Ahura Mazda.

The religious balance erected by Artaxerxes II was continued by his son Artaxerxes III, who popularized the worship of Mithra’s mother, Anahita, through the mass building spree of statues of the Goddess in many important cities of the Empire. Otherwise, we have limited information on the last two final Achaemenids Padishahs, Artaxerxes VI, and Darius III’s religious policy. The obvious answer is that these twilight monarchs of the Empire were consumed with a more pressing matter of foreign policy. That was the rise of Macedonia under Philip II and the conquest of the Empire by Alexander III the Great. We do have the reference of Darius III and his officers praying to Mithra before the famous battle of Gaugamela against Alexander; as Quintas Curtius in his History of Alexander states,

The king himself with his generals and Staff passed around the ranks of the armed men, praying to the sun and Mithra and the sacred eternal fire to inspire them with courage worthy of their ancient fame and the monuments of their ancestors.[29]

Therefore, Mithra's presence in this later period is diminished because of the decline of historical sources. Still, we can assume that Artaxerxes II's policy survived as the orthodoxy until Alexander marched his army into Babylon, deposing the Empire in 330 BC.

Part 3: The Parthians Mithraic Orthodoxy to the Sassanid Neo-Zoroastrianism and the cultural schism between the Persians and Parni

With the arrival of Alexander the Great, who conquered the First Persian Empire, the fate of the cult of Mithra splits into two separate paths, which divide the narrative of the story of Mithra. We have Mithra’s adoption by Hellenic civilization, marking the start of Mithra’s march westward back into the minds of the European Aryans. On the other hand, we have the nomadic Parni who sought to revive the Mithra cult, dreaming of restoring Cyrus the Great’s legacy. However, this turn towards Europeanization of the cult of Mithra shall be dealt with in the following paper; for now, we shall continue to examine the Mithra cult that stayed in Iran after the collapse of the Achaemenid Empire. The Hellenistic period marked a transformative era in the history of the ancient Near East and Iran, particularly following the demise of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE. With Alexander's sudden passing, his vast empire fractured into multiple successor states, each controlled by ambitious generals or Diadochi vying to carve out their own kingdoms or attempt to reunite Alexander’s Empire. Among these successors was Seleucus Nicator, founder of the eponymous Seleucid Empire, who seized control of the heartland of the Persian Empire and established a new era of Hellenistic influence in the region. Inspired by the Persian model of governance, Seleucus initiated a cultural exchange that saw the fusion of Persian and Greek traditions, setting the stage for the emergence of a unique synthesis of beliefs and practices that would see the rebirth of Mithra.

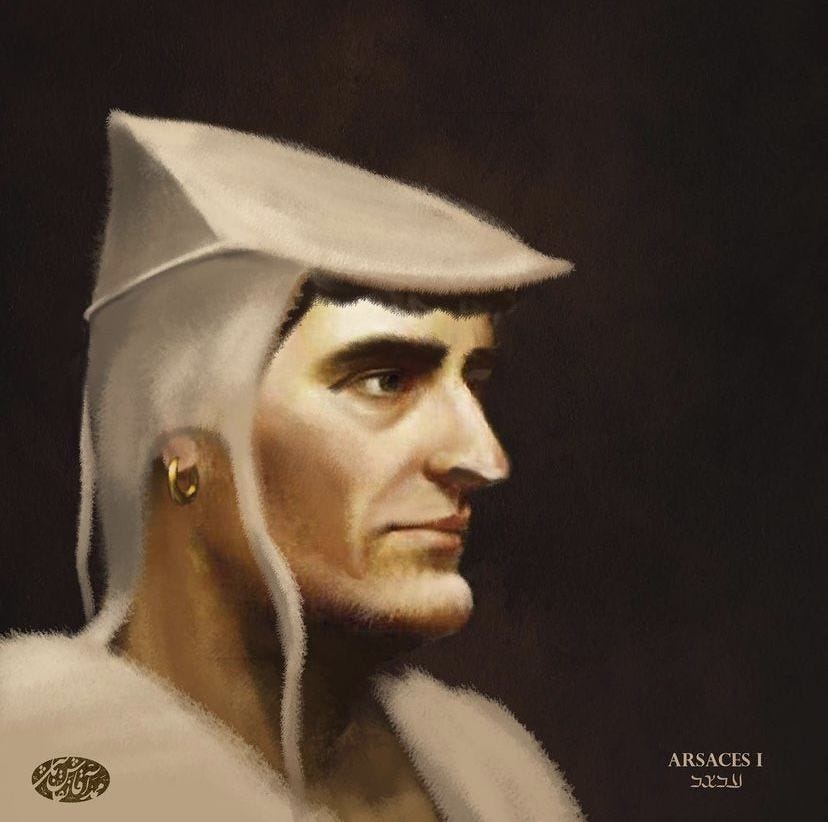

The Seleucid Empire ruled from its capital of Antioch and was a great power in the ancient world since the death of Seleucus. However, as the empire progressed, the Seleucids were losing influence over the far reaches of the empire’s eastern domain. Satrapal revolts, Scythian raids, and the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom succeeding from the Empire created a power vacuum in Iran and Central Asia, which presented an opportunity for various Iranian tribes to assert themselves to be crowned as the would-be restorer of the Persian Empire. Meanwhile, the Mega Basileus Antiochus III the Great waged war with many Iranic invaders, including the Parni, to restore the Hellenic hold of Iran. These Parni or Parthians are a group of nomadic Iranians who, like their Scythian cousins, were Indo-Iranian/Scythian polytheists who sought to reclaim the Persian imperial legacy from both their northern Scythian cousins and the Greco-Macedonian settlers. Led by Arsaces, who adopted the name Ashk, the Parni established the Arsacid or Parthian dynasty in 247 BC, with Ashk becoming the first Arsacid ruler. Notably, the name Ashk is linguistically linked to Mithra, signifying a potential early association with the deity.

Moreover, the spread of Mithraic symbolism, such as the Burzin Mithra fire altar, highlighted Mithra as the preeminent object of worship, reinforcing his status as the patron deity of the Parthian rulers and their subjects. The Arsacid rulers, conscious of cultivating a Persian heritage, strategically aligned themselves with the primordial Mithraism, elevating Mithra to a central figure in their religious and political ideology. Mithra, a solar deity associated with truth, justice, and warfare, resonated deeply with the ethos of the feudal and warlike Parthian society. Moreover, the Parthians' nomadic origins likely contributed to their reverence for celestial Aryan deities, further solidifying Mithra's prominence within their religious landscape. The Arsacid dynasty would launch a series of wars against the Mega Basileus Antiochus III and his Seleucid heirs between 238 BC and 129 BC that would liberate Iran from Hellenic rule and lead to the collapse of the Seleucid Empire, coinciding with Rome’s conquest of Seleucid western holding in Anatolia and Syria ending Greek rule in the Near East and creating the Parthian Empire. Returning to cultural matters, we can see that the reigns of Mithridates I and II, both bearing names honoring the deity Mithra, further underscored the significance of Mithraism within Parthian society. Their choice of theophoric names reflected a deliberate acknowledgment of Mithra's role as a foundational figure in their cultural heritage and the patron of their Empire. Despite adopting Mithraism as a central tenet of their rule, the Parthians maintained the tradition of Cyrus II. They upheld a policy of religious tolerance, allowing various faiths to coexist within their empire, including the Hellenism of the evicted Seleucids on the same level as Zoroastrianism. Especially the tolerance of the cult of Apollo that Parthians like Cyrus before them saw as a Greek veneration of Mithra. This Apollo-Mithra synthesis would allow for the growth of the cult of Mithra in Hellenic communities in the Empire as the Parthians conquered the West.[30] This westward expansion of the Parthian imperium would see the arrival of Mithra into the Greek successor Kingdoms of Asia Minor, establishing the proto-formation of the Cult of European Mithra or the Mithraism of the Roman Empire.[31] However, the Parthian embrace of Mithraism was not without its detractors within the new Parni-lead “Persian” Empire. The Avestan Vendidad text, a part of the Zoroastrian scripture, openly condemns the Parthian elite as sinful due to their deviation from Zoroastrian conventions, such as the burning of the dead and bull/homa sacrifice. Despite these criticisms, the Parthians maintained their allegiance to Mithraism, emphasizing Mithra's role as a unifying force within their empire. The draw of Mithra for the Parthians was his embodiment of what the Platonists called the Hypersonic sun, a God that Henadicly represented the multitude of the polytheist Aryan gods, in this case, Iranian or Greek unifying into a monistic proposition of a singular Aryan God that personifies all of the Gods within the unity of his being. As well Mithra’s veneration was a cultural link back to the Yamnaya, as for the Parthians, a warlike horsebound god and associated with divine fire hinting at the Aryan notion of Apotheosis visive the God H₂epom Nepōts as elucidated in the prior paper. Finally, the Parni worshiped Mithra as he provided the Parthians a cultural identity that allowed them to contrast themselves to the antagonistic cultural identity of the Greek Successors of Alexander and their hegemonic rival of Rome, but as well as a conscious separation from their Persian cousins who were culturally linked to the teaching of Zarathustra. The Parthians were, in many ways, a Hellenized Iranic ruling elite that also sought to take the best of both Hellenic and Persian culture while rejecting other aspects, with Mithra, the primordial Aryan lord, as the civilizational glue to facilitate this synthesis of a new Parthian national Mithraic identity. It seems to be restoring the original Yamnaya sense of the Mithra religion, which was neither European, Vedic, nor Persian but Indo-European or Hyperborean.

The Parthian Empire would spread the influence of Mithra to India in the east, and the West spread Mithra to Armenia; as Strabo states, “the satrap of Armenia used to send annually to Persia twice ten thousand colts for the Mithraic festivals.”[32] As well as the aforementioned, the slow integration of the Mithraic mysteries into Greco-Roman religion and Stoic and Platonic philosophy shows a seemingly cultural conquest of Rome. It seems that in the opinion of Jorjani, the Parthians were on the verge of some grand cultural conquest of the various Aryan peoples of Eurasia by religious conversion, much like the Christians did in early Medieval Europe, as he states, “a time when the Iranian religion of Mithraism was about to build a bridge between pagan Rome and Mahayana Buddhist northern India”[33] However this ideal of a new spiritual and hegemonic Mithraic Empire Spanning form the Ganges river to the Britannia with Ctesiphon at its heart was undercut by the primordial flaw of the Empires fundamental character, that be decentralization or de facto federalism of the empire which would doom the Parni. Being a cultural nomadic/aristocratic society, the Parthian Empire was much like the Holy Roman Empire of medieval Europe, which is to say the Parthian Empire was an Empire on paper but, in reality, was a collection of feudal demesne. The Parthian nobility was semi-independent and tied the Padshah by convention and feudal obligation rather than the autocratic legalism seen in ancient China or the Late Roman Empire; consequently, civil war was a common phenomenon of the Parthian Empire. Thus, it was during another one of these constant civil wars that plagued the Parthian state that a Persian nobleman, Ardeshir Babakan, hailing for the Persian homeland of Pars, rose up, backed by the Zoroastrian clergy, launched a noble and religious revolt against the Parni. Ardeshir would defeat the Padishah of the Parthian dynasty, Artabanus IV, and proclaim the Second Persian Empire or as it is known to history, the Sassanid Empire.

The new Shahanshah Ardeshir, who was in civilizational terms a historical parallel to Constantine and Theodosius in Rome, was a radical monotheist who suppressed all cults with particular zeal, crushing the worship of Mithra to create a new state-mandated Zoroastrian Orthodoxy like in Rome, where the Christian Church used the state to crush any native Greco-Roman religious institution or belief. Ardeshir tasked the Zoroastrian clergy, led by inquisitors Tansar and Kartir, to root out and suppress Mithra as the God of the prior regime and the popular God of the Iranian peoples within the Empire in a brutal campaign in killing suspected heretics and desecrating temples.[34] Ardeshir created a theocratic and totalitarian state comparable to the policy of the Dominate era Roman Empire as; well the Sassanid regime was also heavily driven by xenophobic Persian nationalism as

Ardeshir anachronistically held the Romans responsible for Alexander’s conquest of Iran, and from the outset he stated his intention to re-conquer all of the territories of the first Persian Empire that had become part of the Roman Empire. Given his puritanical monotheism and the mercilessness with which he was attempting to eradicate Mithraism in his own country, by closing down the majority of fire temples (daré Mehr) in Iran on account of their being too pagan, the Romans must have seen his rise to power as a grave threat — not only from a military standpoint, but from a sociological one as well.[35]

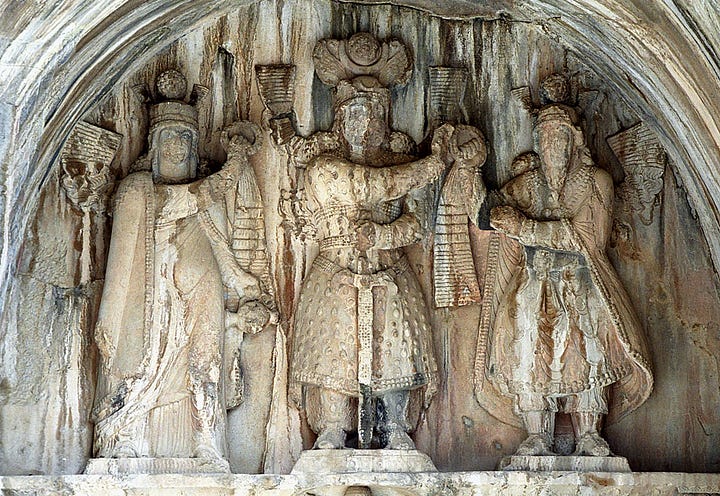

The Sassanid Empire’s hostility to Rome may as well be related to the Mithraic influence that they were suppressing at home was taking over the Roman Empire, as can be seen with the reigns of Antonius Pious to Diocletian and the brief reign of Emperor Julian the Philosopher, as the cult was slowly becoming a critical religious institution in the Roman system. Mithra, lord of the Aryans, was deemed heretical; his doctrine was suppressed, and his temples were closed. However, references to Mithra would survive but in diminishing quantity. Mithra was kept on as a Yazata as Zarathustran clergy intended, as they could never expunge Mithra or his mother, who held the faith of the masses. Despite Ardeshir's puritanism, the Mithra cult would survive because of its aristocratic appeal as the lord of noblemen and Emperors alike. The attacks on Mithra’s persecution would lighten up as Ardeshir’s successors took the throne. Thus, the cult would merge in a diminished form with the Zoroastrian orthodoxy. Mithra would still appear in Imperial iconography until the end of the empire as Mithra was, and his relevance was too entrenched to be removed, with such examples below.

However, the Sassanid view of Mithra would shift from a policy of tolerance or persecution depending on the ruler until the end of the Empire. This schism of Mithraic persecution played a role in the collapse of the Sassanid Empire. While the Sassanids were chauvinistic Persians and Zoroastrians that were strongest in the south of the Empire was Persian, in the north of Iran, Armenia, and the central Asian part of the Empire was the Parthian nobility from the prior regime. This divide between a Persian Zoroastrian south and a Parthian Mithraic north created a similar schism in the Roman Empire between Mithraists and Pagans contra Christians. The Northern Parthian lords in Tabaristan, the House of Mihrān, the House of Karin, and remnants of the old imperial Arascid dynasty ruling Armenia, defiant in their religious belief, created a sense of instability in the Empire, launching a series of civil wars between the Parthian Nobility and the Persian imperial core, sapping the Empire’s strength. This divide would facilitate the necessary division that allowed the forces of Islam to conquer the Sassanid Dynasty as the Parthian nobility abandoned their Shah and his Persian army to be defeated, causing the fall of the Aryan Imperium to Islam; Pourshariati obliquely and Jorjani explicitly argues that the Parthians of the Karin may have been the Green-clad army of Islam that helped the Muslims defeat the Shah collapsing Sassanid rule.3 If this act of betrayal is true, then it was the final poison harvest of the Sassanid policy of religious zealotry, needlessly antagonizing the Parthian nobility instead of fostering unity. The fall of Persia to Islam would end the worship of Mithra in official terms (I will address the possible survival of Mithra in medieval and modern Greater Iran in a later paper), causing an end to 2650 years of Mithraic influence within the Greater Iranian cultural sphere. Mithra would be rehabilitated in the Islamic period in Zoroastrian circles in the text of the Bundahishn written in the post-conquest period. In this text, Mithra was restored to a solar god in the Zoroastrian faith and a key figure in the eschatological fate of the world in the Zoroastrian faith, leading the forces of light against the darkness at the end of days, as M. J. Vermaseren in work, Mithras, the Secret God states,

The new reign of the Sun-god has now begun. And then when the dead have risen from their graves, the Saushyant will, according to the Bundahishn (xxx, 25) slay a magnificent bull and make a potion of immortality for mankind from its fat, mixed with the Haoma juice. This Messiah is represented in the Western mysteries by none other than the Sun-god Mithras himself. A Latin inscription from Rome says: ‘hail to the Saushyant’ (nama Sebesio), while a Manichean document found in Turkestan adds another special feature. In contrast with the true Mithras is a false deity who rides on a bull (see plate opposite p. 33 and p. 113) and pretends to be the ‘true son of God’. He commands men to worship him. In the Bundahishn (xxx, 10) the powers of Good and Evil are to be separated after the final battle and Mithras is one of three who pass judgment on the soul when, according to the Avesta, the dead arrive at the bridge Cinvat. But at the end of time Mithras will guide the souls through a blazing stream which can harm only the evil ones.[36]

Despite his shifting permeance in the land of Iran, Mithra played an outsized role in the religious history of the Iranian peoples from the bronze age BMAC Aryans to the fall of the Sassanid Empire. Thus, despite the Zoroastrian attempt to suppress his majesty, Mithra played an essential role in shaping Iranian culture as he did in Vedic and Buddhist India and played a crucial role in the modern Zoroastrian faith. The collapse of the Sassanid Empire and the Islamization of Persia end our story of Mithra in Iran and our examination of the ancient eastern Aryan veneration of Mithra since the Indo-European migration. In the following paper, we shall rewind the clock to the growth of European Mithraism in the wake of the decline of the Seleucid Empire along with Roman and Parthian expansion, to show how the Persian-Parthian cult used Anatolia as the cultural laboratory to make the societal jump via Hellenism reintroducing Mithra to the Aryans of the West to the Greeks and take hold in the Roman Imperium. (Continue below)

Mithra, The Hidden Sun of The Aryans Part 3: The Arrival of Mithra into the Hellenistic World

The Hellenic Mithra story is a compelling testament to the intricate tapestry of religious syncretism that characterized the ancient world. Rooted in the adoration of Mithra, a deity originating in Persian mythology, this cult underwent a fascinating journey of adaptation and dissemination in the Hellenistic world, ultimately flourishing within the cult…

Bibliography

Athenaeus of Naucratis. The Deipnosophists, IV, Books 8-10. The Loeb Classical Library. Harvard University Press, 1930.

Colledge, Malcolm A.R. The Parthians. Praeger, 1967.

Cook, John Manuel . The Persian Empire. Schocken, 1983.

Cooper, D. Jason. Mithras: Mysteries and Initiation Rediscovered . Weiser Books, 1996.

Curtius Rufus, Quintus. THE COMPLETE WORKS of QUINTUS CURTIUS RUFUS . [S.l.]: DELPHI CLASSICS, 2017.

Evola, Julius . Metaphysics of War : Battle, Victory & Death in the World of Tradition. Editorial: S. L.: Arktos, 2011.

Jorjani, Jason Reza. Iranian Leviathan : A Monumental History of Mithra’s Abode. London: Arktos Media Ltd, 2019.

Kuhrt, Amélie . The Persian Empire : A Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period. London: Routledge, 2007.

Olmstead, A T. History of the Persian Empire. University of Chicago Press, 2022.

Strabo. Geographica. Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Vermaseren, Maarten Jozef. Mithras, the Secret God. New York : Barnes & Noble, 1963.

West, Martin L. Indo-European Poetry and Myth. OUP Oxford, 2008.

[1] D. Jason Cooper, Mithras: Mysteries and Initiation Rediscovered (Weiser Books, 1996), 1.

[2] A T Olmstead, History of the Persian Empire (University of Chicago Press, 2022), 24-25.

[3] Strabo, Geographica, XV. 3:

[4] Olmstead, 26.

[5] Martin L West, Indo-European Poetry and Myth (OUP Oxford, 2008), 252.

[6] Julius Evola, Metaphysics of War : Battle, Victory & Death in the World of Tradition (Editorial: S. L.: Arktos, 2011), 33-4.

[7] Olmstead, 98/281.

[8] Ibid, 96

[9] Maarten Jozef Vermaseren, Mithras, the Secret God (New York : Barnes & Noble, 1963), 15-6.

[10] Olmstead, 478.

[11] Jason Reza Jorjani, Iranian Leviathan : A Monumental History of Mithra’s Abode (London: Arktos Media Ltd, 2019), 17.

[12] Jorjani, 65-6.

[13] Ibid, 56.

[14] Jorjani, 56-7.

[15] Ibid

[16] Ibid, 475-6.

[17] Ibid, 58-9.

[18] Ibid, 58.

[19] Ibid, 57-9.

[20] Olmstead, 132.

[21] Cook, John Manuel . The Persian Empire. (Schocken, 1983.),140-150.

[22] Athenaeus of Naucratis, The Deipnosophists, IV, Books 8-10, The Loeb Classical Library (Harvard University Press, 1930), book 10, ch.45.

[23] Ibid

[24] Jorjani, 39.

[25] Amélie Kuhrt, The Persian Empire : A Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period (London: Routledge, 2007), 407.

[26] Olmstead, 471.

[27] Jorjani, 36.

[28] Ibid Jorjani, 37-8.

[29] Quintus Curtius Rufus, THE COMPLETE WORKS of QUINTUS CURTIUS RUFUS ([S.l.]: DELPHI CLASSICS, 2017).book 4, chapter. 13.

[30] Malcolm A.R. Colledge, The Parthians (Praeger, 1967), 108.

[31] Colledge, 102-3.

[32] Strabo, XI. 14:

[33] Jorjani, 194.

[34] Ibid Jorjani, 192.

[35] Jorjani, 194.

[36] Vermaseren, 26.

Bryant, Edwin F. The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate. Oxford University Press, 2001.

Parvaneh Pourshariati, Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran, 358.

Pourshariati, 380